‘The blight seeped into your soul’: How Seven reflected fears in the US in the 1980s

David Fincher’s gritty thriller commented on the urban blight and religious conservatism of the Reagan era. But it also predicted our obsession with true crime today.

Thirty years after its release, David Fincher’s Seven is now celebrated as the zenith of neo-noir crime thrillers. It raked in a whopping $327m (£250m) at the box office on a $34m (£26m) budget and earned raves from most critics when it came out in 1995. Still, the persistent argument against the film is that it relies too heavily on shock-and-awe gruesomeness to distract from its paper-thin ideas and shopworn crime tropes. A Washington Post critic lambasted Seven for disguising “formulaic writing” with gratuitous “bloodletting”, while a New York Times reviewer lamented that “not even bags of body parts… keep it from being dull”.

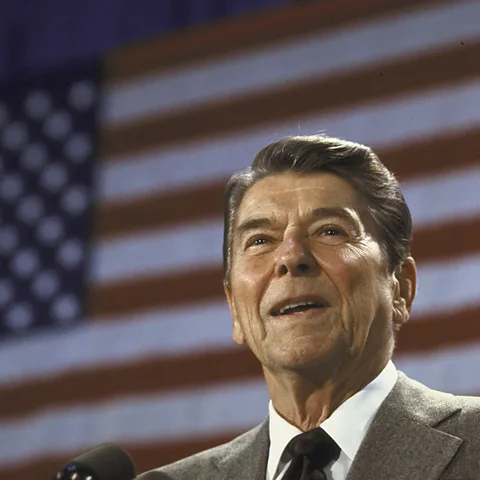

Three decades on, however, it’s clear that some critics missed a different layer to the film – namely, how it interpreted the US’s social crises of the 1980s. There was a worldwide recession at the start of the decade, and this coincided with high urban crime rates, a crack cocaine epidemic and the spread of Aids. The US’s new president, Ronald Reagan, responded to these issues with talk of being “tough on crime”, and his high-profile supporters included various influential Christian figures – leaders of what was known as the Christian right or the religious right – who preached the importance of traditional family values.

All of this fed into Seven. On one level, the film is an exquisitely well-made thriller about a psychopathic serial killer, but beneath its noir-style veneer lies a fascinating take on the way the US responded to some of its most divisive social issues.

The film’s heady premise is easily unboxed. Two detectives, jaded veteran William Somerset (Morgan Freeman) and quixotic rookie David Mills (Brad Pitt), pursue a polymathic serial killer known as John Doe (Kevin Spacey, stealthily absent from the opening credits) as he orchestrates murders in a symbolic parallel with early Christianity’s seven deadly sins. The trail starts with the corpse of an obese man, targeted for the sin of gluttony, whose stomach ruptured after being forced at gunpoint to gorge himself. As the other murders unfold, the detectives flail about without doing much detecting until John Doe inexplicably surrenders himself. The twist comes when Mills discovers what’s inside a courier-delivered cardboard box – it’s his wife Tracy’s (Gwyneth Paltrow) severed head – and in the now iconic climax, he succumbs to the seventh sin of wrath by killing John Doe on the spot.

I realised after a while that I’d become inured to the sounds of gunshots – Andrew Kevin Walker

Unlike the mysterious John Doe, the film does have a traceable origin story. Andrew Kevin Walker wrote the original script across three years in the late 1980s after moving to New York in 1986 and getting a job at Tower Records in the Astoria neighbourhood in the borough of Queens. He’d grown up in the rolling hills of central Pennsylvania, and his immersion in the concrete jungle of New York, then ravaged by crime waves and the crack and Aids epidemics, was a visceral shock.

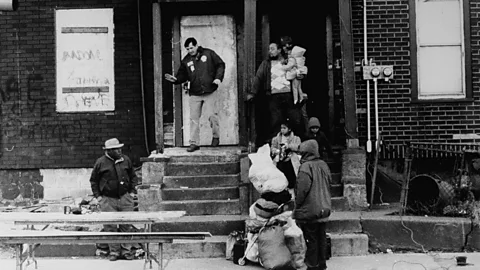

“Every time you’d walk up a stairwell, the crack vials would crunch underfoot,” Walker tells the BBC. “Trash accumulated on the sidewalks, and I realised after a while that I’d become inured to the sounds of gunshots. Across a week, you’d see a car abandoned, then its windows smashed and tyres stripped, and by Saturday it’d be a burnt skeleton. It felt like an external blight that eventually seeped into your soul and hollowed you out.”

These may just have been Walker’s own personal impressions, but reports from the time show that urban crime was on the increase: a New York Times article in January 1987 stated that homicides in some of the nation’s largest cities had risen sharply in 1986. And Walker’s experiences were echoed in political speeches of the decade. “Many of you have written to me how afraid you are to walk the streets alone at night,” said Reagan in a 1982 radio address. “You have every right to be concerned. We live in the midst of a crime epidemic that took the lives of more than 22,000 people last year and has touched nearly one-third of American households.”

To create the atmosphere for Seven, Walker and Fincher linked Walker’s personal observations of disorder with the “broken windows” theory. This was a criminological concept, elaborated in a 1982 issueof The Atlantic, which argued that visible signs of vandalism create a positive feedback loop that triggers even more destruction and criminality. Seven featured such signs in its dilapidated interiors – peeling paint, cracked plaster, fetid garbage, and roach-infested floors – and the industrial atrophy of rusted metal and scorched brickwork.

But it was the human misery, Walker says, that really struck him. “Every morning on my way to work, I walked past scores of homeless people desperately panhandling, too many to ever help, their children loitering alongside them and peeing in the street gutter,” he says. “When you’re faced with that daily, you end up with a carapace of apathy to ward off the guilt.”

Serial killers and televangelists

Walker wanted to depict a world numb with apathy, but also an antagonist, John Doe, who soaks in the suffering around him like a sponge. He made the character a serial killer – again, a choice derived from reality. A glut of news reports about real-life serial killers across the 80s had made such figures as Jeffrey Dahmer, the Golden State Killer, Richard Ramirez, and the Muswell Hill Murderer household names. As it turns out, that perception of a spike in serial killings was not simply a media distortion but a measurable reality: such killings soared in the late 1970s and peaked in the 80s before falling again in the last decade of the century.

Meanwhile, President Reagan’s criminal justice reforms – tougher punishments, expanded law enforcement powers, and increased incarceration – came wrapped in uncompromising rhetoric. ”The American people want their government to get tough and go on the offensive,” the president said in 1986, as he signed an anti-drug bill into law. “And that’s exactly what we intend, with more ferocity that ever before.”

The character of John Doe in Seven caricatures that attitude, although Andrew Hartman, an academic historian and expert on the culture wars of the late 20th Century, said that it would be wrong to suggest that the film sided with either right-wing or left-wing political parties. “Seven itself doesn’t sermonise,” he says, noting that when Democrat Hillary Clinton was the first lady in the 1990s, she “took up the tough-on-crime mantle”. In 1994, Clinton declared: “We need more police, we need more tougher prison sentences for repeat offenders… We need more prisons to keep violent offenders for as long as it takes to keep them off the streets.” And Clinton was hardly associated with the Reaganite right. “These ideas about criminality ebb and flow across political parties,” says Hartman.

In creating John Doe in Seven, Walker drew on notions of sin, damnation, and divine punishment that were increasingly common in the public sphere. Prominent evangelicals like Jerry Falwell Sr, for instance, a Baptist minister and founder of the Moral Majority, railed against “the pornographers, the smut peddlers, and those who are corrupting our youth”. Meanwhile James Dobson, founder of the global Christian ministry Focus on the Family, sought to restore a God-fearing obedience in children through corporal punishment on the theory that “pain in a marvellous purifier”. And televangelist Pat Robertson predicted impending Armageddon based on “certain signs, or clues, that His coming is approaching”.

Hartman sees parallels between this language and the language in Seven – as exaggerated and distorted as it is when it comes from John Doe. “As the religious right reasserted itself at the centre of culture and the American ethos, it blamed a permissive culture of hedonism for shattering families, igniting the Aids crisis, and unleashing delinquency,” he says.