Repairing broken gadgets for a greener future

The January sales is a time when many shoppers will be looking to replace faulty electrical items.

But instead of buying new gadgets, a movement of volunteers wants people to repair their old ones to save them from landfill.

Repair centres, where people can learn repairing skills, have been springing up across the UK, and include the Fixing Factory on a high street in Camden, north London, which opened at the end of October, following the success of a centre in neighbouring Brent.

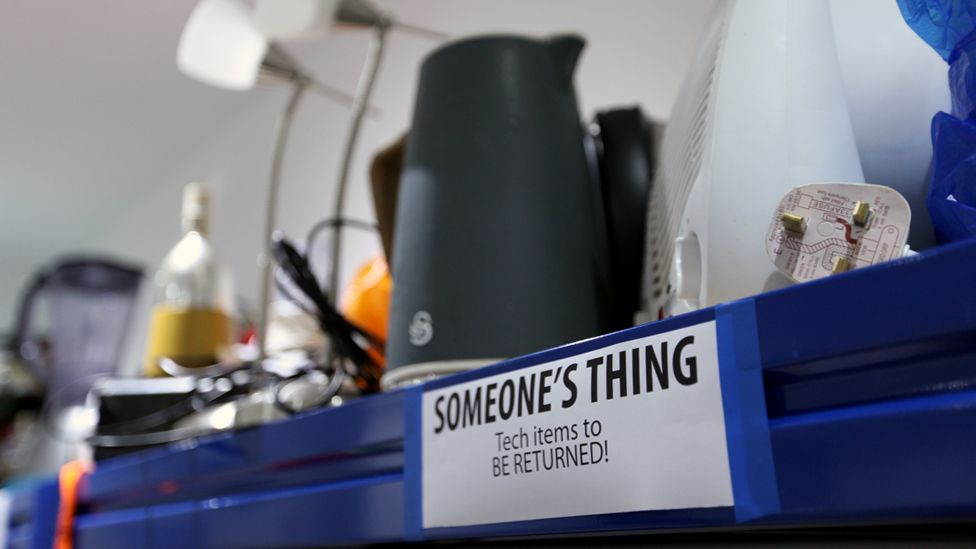

In the backroom of the Camden branch there are shelves of faulty items awaiting careful attention.

Broken toasters, lamps, laptops, kettles and heaters adorn the blue shelves. There is even a wonky Polaroid camera.

“A lot of us are feeling pretty powerless in the face of the climate crisis,” Dermot Jones (below, second left), project manager for the Camden branch, says. “Throwaway consumerism and the escalating cost of living just compounds that powerlessness.” Enabling people to get “hands-on” with repairing their own stuff hands them back some of this lost power.

Dermot has been fixing things his whole life.

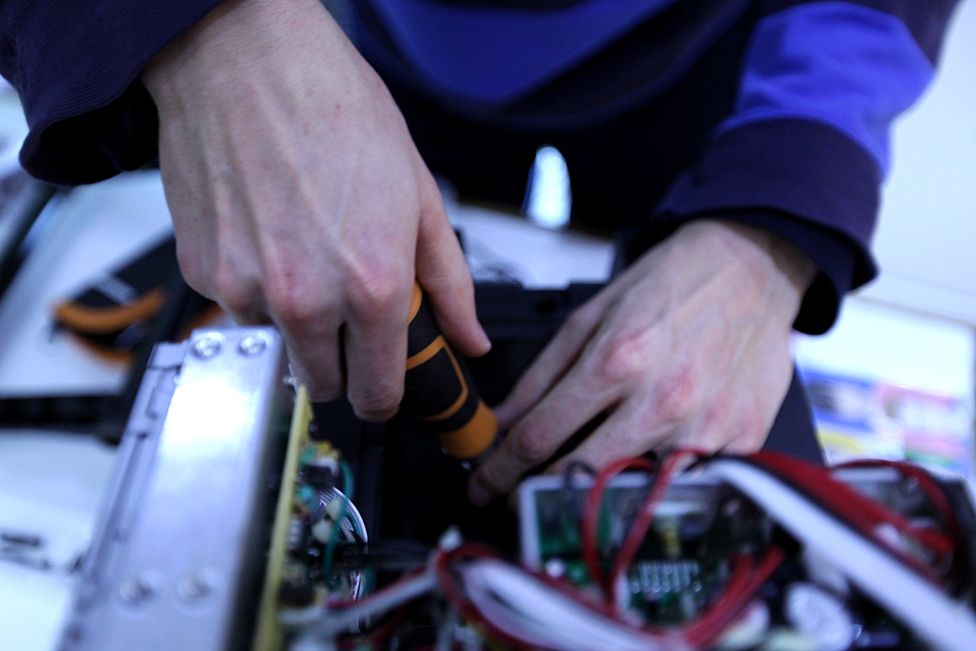

On a Tuesday evening in November, Dermot helps volunteer Harry (below, right) with a broken portable speaker at the Camden branch as part of a weekly Repair Club.

Harry was a volunteer at a repair cafe when he lived in the US during the pandemic. There, he specialised in repairing laptops for the public.

After Harry examines the speaker’s electrical innards with fellow volunteers Stephania and Tony, they identify the problem: the rechargeable battery can no longer hold an electrical charge.

A replacement is fitted and the room fills with the sound of Caliban’s Dream by Underworld – one of Harry’s favourite tunes, which he streams from his phone.

The Fixing Factory estimate that 80% of all broken electrical items could be repaired at community events. This year, 5.3 billion mobile phones will be thrown away, according to an international expert group dedicated to tackling the problem of waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE).

The WEEE forum says the “mountain” of electrical and electronic waste – from washing machines and toasters to tablet computers and global positioning system (GPS) devices – will grow to 74 million tonnes a year by 2030.

At the Repair Club, volunteer Tony (below) is working on a bladeless fan.

The retired former BBC radio engineer, 79, has seen a lot of technological changes in his lifetime. Tony joined the broadcaster in 1963 and recorded classical concerts, among other things. He fixed amplifiers using a soldering iron and remembers working with radio valves instead of transistors.

“Things were once designed to last,” explains Tony.

But changes in engineering methods have led to some products “only lasting to the end of their guarantee”, he says.

He opens up the base of the fan he’s trying to fix and cleans out the collected dust inside.

“The thing that annoys me are bits of plastic inadequately engineered, so an item has to be thrown away when it breaks,” he says.

He puts the fan back together and turns it on.

Cold air blows from the oval mouth, but when the dial is turned to warm air, the temperature stays stubbornly cool.

“It’s promising progress,” he says.

Another volunteer, David, joined the group after the Fixing Factory rescued his faulty laptop. He almost lost precious photos of his late mother on his computer, along with important documents.

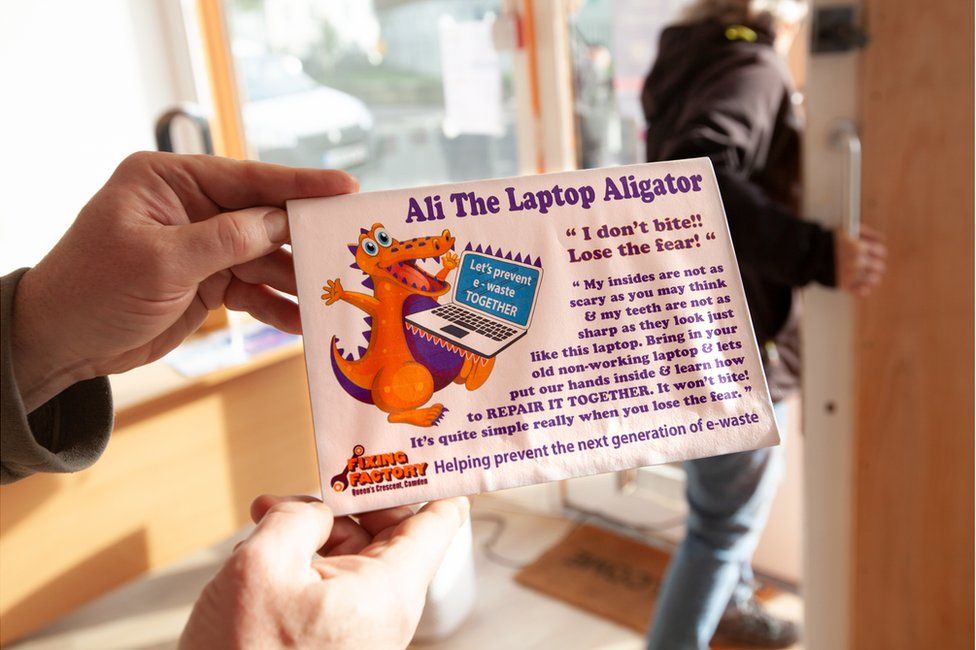

“There’s a lot of fear in fixing things,” he says. “Tinkering with a laptop you know nothing about is like putting your hand into an alligator’s mouth.

“The repair trainer showed me that the alligator’s mouth won’t shut. They helped demystify the process for me.”

David designed a small poster encouraging people to confront their fear of the “alligator”.

Safety is at the forefront of the Fixing Factory’s activities, Dermot says.

Everything that leaves the site is given a portable appliance test (PAT), he explains, and mains voltages are only ever exposed in highly controlled circumstances when it is absolutely necessary.

Volunteer Petra (below) is trying to fix a smart watch.

It is a recent model that she bought for £30 off eBay, where it was listed as not working due to a charging issue.

Volunteer Lisa (below, right), who is fixing a friend’s radio, says she is volunteering for sustainability reasons.

There are no repair centres where she lives in Waltham Forest, she says, and hopes one will open.

“There needs to be huge changes in the way our stuff is made,” says Dermot. He believes manufacturers could make a big difference to their customers and the climate if they worked with projects like Fixing Factory.

Change in the industry may indeed be coming.

In December, Apple rolled out its self-repair service to the UK and seven other European countries.

iPhone 12 and 13 users, and some Macbook owners, will be able to fix their own devices by buying parts and tools and watching online tutorials.

Midway through the evening, a passer-by walks in.

Noor, 27, says she was intrigued by all the colourful signage outside and the lively activity inside.

“I’ve never seen anything like it in Camden,” she says. “It’s very useful, especially in the economic crisis. It’s good to learn.”

She promises to return the following week with her 18-year-old brother. But just 20 minutes later she’s back in the Fixing Factory again.

“I’ve brought the family,” she says, with her brother and another member in tow.

On Thursday afternoons, the Fixing Factory invite the public to bring along their broken items for the team to look at – and hopefully repair – at no charge.

It is similar to the concept behind the BBC’s Repair Shop. But whereas the team on the programme often fix items for sentimental reasons, Dermot and the volunteers focus on doing so for practical ones.

Marilyn (below) brings along a broken kettle.

Working with Dermot, they discover that a copper connection has become coated by a layer of carbon from a tiny spark each time the kettle is turned on, causing the switch to no longer work.

They scrape away at the corroded contact with a paperclip.

They put it back together and turn it on in tense anticipation.

The low rumble of boiling water can soon be heard, and then the ding of a small bell as the water boils, followed by cheers from those looking on.

“Personally I love what I like to call the ‘cup of tea’ fixes; a repair that takes the same time as drinking a cuppa and the parts cost less than a cup of tea,” says Dermot.

“These bust the myth that it’s simply not cost effective to fix things nowadays and that it takes too much time and effort.”

As more visitors bring their broken items, members of the public stop and watch the fixers at work with interest. It is like a new spectator sport.

“In 2023 we’re aiming for a proliferation of similar projects,” says Dermot.

“In a year or two, I want every town to have a place where you can take stuff to be fixed and for it to be a mini industry in itself.”

“[I want] a new generation of repair technicians and a culture and ethos in the public of wanting to get their things fixed.”