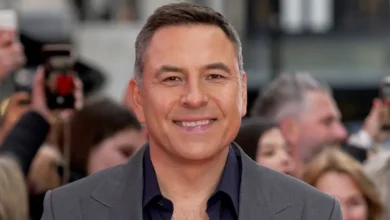

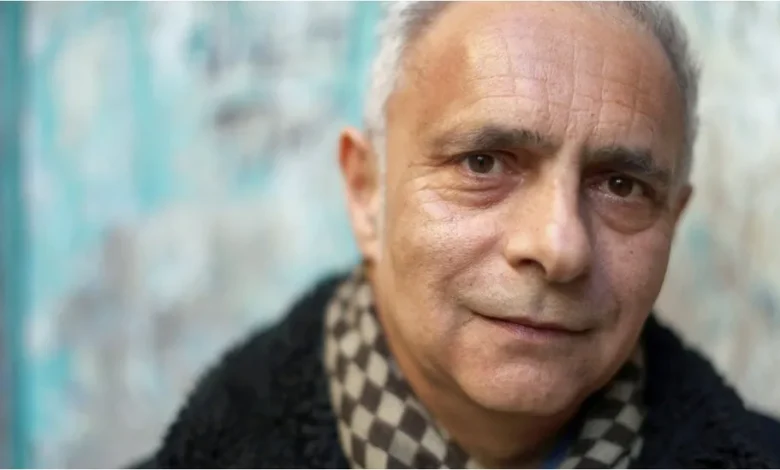

Hanif Kureishi: I’ve become a reluctant dictator

Novelist Hanif Kureishi sustained life-changing injuries when he collapsed and landed on his head on Boxing Day last year.

Left without the use of his arms and legs, the award-winning writer of The Buddha of Suburbia and My Beautiful Laundrette has charted his experience in brutally-honest blog posts. He credits his sense of purpose to his relationship with his responsive readers.

A year on, he joined BBC Radio 4’s Today programme as a guest editor and described the accident’s profound impact on his life.

“I thought, ‘I’ve got a few more breaths and then I’m going to die.’

“Then I thought, as I guess many people do when they die, that ‘this is ridiculous to die in such a stupid way. Surely I could do something a bit more dramatic, a bit more interesting to tell people’.

“I also had a sense of thinking, ‘There’s lots of things I really want to do, I’m not ready to die yet.'”

Kureishi’s thoughts in the moments after his accident were remarkably lucid. The 69-year-old was staying with his partner Isabella in Rome when he fainted after a walk. He woke up lying in a pool of blood.

“I thought I might FaceTime a few friends actually, while I was lying there waiting for the ambulance, and say goodbye. But Isabella said it wasn’t such a great idea, that people would be rather shocked by seeing a dying man pop up on their iPhone.”

Although Kureishi had been unwell with an infection, his collapse was unexpected. His sense of outrage at his fate is shared by fellow patients who were badly injured in sudden accidents.

“One guy fell out of bed and broke his neck. People fall down the stairs. People fall into swimming pools. It’s a catalogue of farcical and cruel, contingent, meaningless events.

“There’s a guy I was talking to the other day, he was in his garden, he tripped over a rake and broke his neck. He was absolutely outraged by the injustice of what had happened to him.

“It’s very common, with these kinds of circumstances, [to feel] that you’ve been plucked out of the world at random and punished in some kind of Kafkaesque way.

“But then you get a much broader sense that this happens all the time to people.”

Kureishi says he is still the same person he was a year ago, but has lost his sense of humour – and innocence.

“I was quite a jaunty fellow, I went around the world quite cheerfully, I enjoyed walking about and seeing things and talking.

“The world seems much darker. And you look at all those innocent people strolling around the world looking so healthy and fit and happy and you think: ‘You don’t know guv, what’s coming down the road.’

“And that’s a very cruel and cynical way of seeing things, but you’ve gone through a door when you have an accident in the way that I had an accident.

“But in a sense I feel that I’m much closer to reality – that, in a way, we’re living in some kind of nirvanic miasma until something like this happens.”

Over the past year, Kureishi has been treated in five different hospitals in Italy and then the UK. His paralysis has transformed his relationships.

“I can’t even make a cup of tea. I can’t scratch my nose. So I’ve had to learn to make demands. I’m a reluctant dictator.

“There are friends and acquaintances who have been absolutely devoted – people you wouldn’t necessarily have thought of as being particularly like that.

“You’ll find that one particular person might volunteer to bring you food, to give you a head massage, to sit with you, to make phone calls for you, to do your emails for you, everything.

“There are other people – more men actually, I would say, than women – who just can’t bear to be in a hospital. And you can see them looking at their watches, thinking: ‘How the hell do I get out of here and how soon can I leave?’ because it’s such an awful thing to see all these people in wheelchairs and crippled people staggering around the corridors, and they all think: ‘God, it’s gonna be me next.’

“I was like that before, because I spent a lot of my teenage years in hospital with my father, who was very ill for a long time. So I have a horror, phobia of hospitals with reason, and now I live in the hospital. That’s an irony for you isn’t it?

“But to be struck with an illness like mine, you suddenly see what other people are made of, and who they are, and how generous and kind they can be, or how indifferent they can also be.”

In fact, Kureishi has observed that becoming disabled has given him a strange power.

“One of the things that happens to you when you’re disabled is that you feel less powerful, that you’re a sort of impotent god for your kids, but actually in another sense you are more powerful. You’re incredibly powerful.

“People are really drawn towards you because of your illness, they’re fascinated by it and they wonder when it’s going to happen to them.

“You can’t say that it does nothing to people. It’s very moving, very upsetting and life changing for other people around you.”