James Graham and Barry Sloane on reviving landmark 1980s TV drama

It regularly appears on lists of the greatest TV dramas ever – now Boys From the Blackstuff is having its stage premiere in Liverpool. Can the unflinching story of unemployment speak to us in 2023?

A door opens and a stream of cheerful actors and crew members emerge into the daylight for a break from their rehearsals.

Then another figure appears in the doorway wearing a black T-shirt and black jacket, with black hair and a distinctive black brush moustache.

His eyes look black too, and empty. Maybe he’s still in character. Maybe it’s just the effect of a hard morning’s rehearsals.

Either way, he’s unmistakeable, uncanny, and highly unsettling.

The man silently sticks out a hand. I fully expect him to introduce himself with the words: “I’m Yosser Hughes. Giz a job,” followed by a swift headbutt.

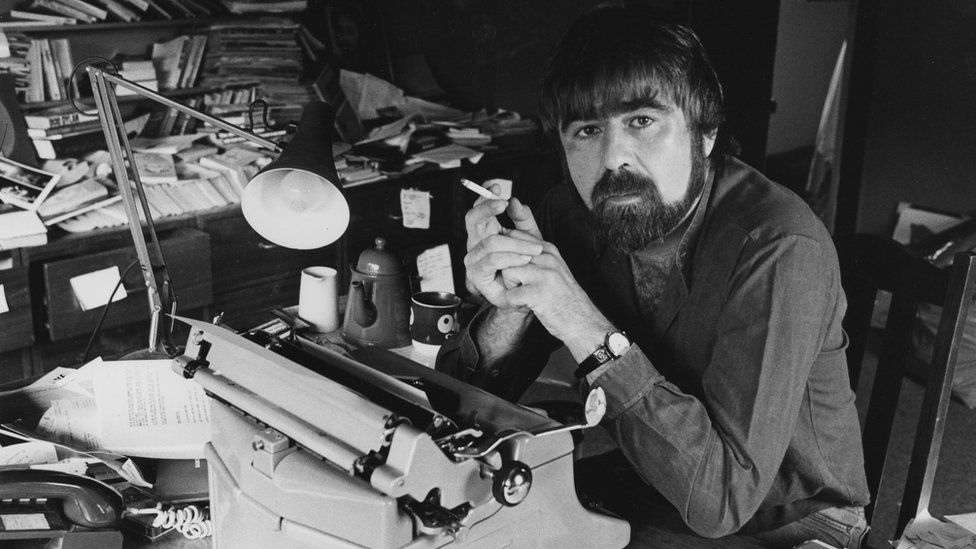

Yosser Hughes was one of the characters who struggled – and in Yosser’s case, often failed – to keep their heads above water amid Liverpool’s rampant unemployment and industrial decay in Boys From the Blackstuff.

He became one of the most intense and memorable characters in British TV history, and his image and catchphrase were imprinted on British culture in the 1980s.

The show won a Bafta for best drama series in 1983, and in 2000 was ranked seventh on a British Film Institute list of the best TV shows ever made.

Yosser was played by Bernard Hill on TV. For the first stage adaptation, he is being portrayed by Hollyoaks and The Bay actor Barry Sloane, who’s also known for playing Captain Price in the Call of Duty games.

‘Very emotional’

The new Yosser goes to get “de-moustached”. A few minutes later Sloane reappears, transformed without Yosser’s lip-slug and wearing an Oasis T-shirt.

The moustache is a recent addition to rehearsals. “I feel like his cockiness jumped up a notch today with the moustache,” director Kate Wasserberg tells the actor. “It was really good. The moustache of power.”

“Just a bit of face acting, you know,” Sloane smiles.

What’s it like playing such a full-on character? “It’s a joy,” Sloane replies, before adding: “It’s difficult. It’s the kind of role that requires a full buy-in and full commitment, which I’m excited and proud to do.

“This [show] means something. It gets me very emotional just to play him because it’s so intense to be tied in to this. It’s my father’s and grandfathers’ generation we’re talking about.”

Sloane spent his childhood in Liverpool “in the embers” of the problems that writer Alan Bleasdale depicted on screen.

Boys from the Blackstuff followed five men who worked on a tarmac crew before returning to their home city to discover there were no jobs – except illicit cash-in-hand ones that got them in trouble with a cruel benefits system.

Yosser was the most extreme of the five, apparently having been driven to the brink of sanity. Bleasdale has spoken about basing him on a real man who once walked into a cafe and ordered six plates of poached eggs before proceeding to headbutt each one in turn.

“These are real fellas, yeah,” Sloane says. “There are many Yosser Hugheses among us, lest we forget.”

Wasserberg describes Yosser as “the human wreckage of what happens when someone wholeheartedly buys into the Thatcherite dream and it betrays them”.

Boys From the Blackstuff first aired in 1982, three years after Margaret Thatcher became prime minister, and is often held up as the most powerful portrayal of the effects of her policies on northern cities.

Writer James Graham, known for TV dramas Sherwood, Quiz and Brexit: The Uncivil War, plus plays about Gareth Southgate and Rupert Murdoch, has adapted the series for Liverpool’s Royal Court theatre, in collaboration with Bleasdale himself.

“A disproportionate amount of pain was being inflicted upon certain communities in this transition from the 70s into the 80s,” Graham says. “People can agree or disagree with the necessity for that. That’s not the what the show is about. The show is about the human cost of that.”

In fact, Bleasdale wrote most of the scripts before Mrs Thatcher came to power – docks and factories had been closing throughout the 70s – but the show captured the shock places like Liverpool felt under her tenure. The city’s unemployment peaked at more than 20%, double the national average, in the mid-80s.

‘Wit and mischief’

Coming from a former mining village in Nottinghamshire, Graham says he felt affinity with Liverpool’s plight. “I think we should have an anger about the level of pain that was inflicted,” he continues.

“What Alan did so beautifully and radically was to not shy away from it, but to look at the real scale of that human suffering and how that meant families and friends turning on each other and a city turning on itself.

“But that also makes it sound really worthy and depressing.

“What else he did that was really radical was give such humour and wit and mischief to this, and build such vivid, extraordinary characters like Yosser Hughes, who’s an icon of this city and of British television.”

Like the TV show, the stage play is set in the early 80s. While the city has changed in many ways, Graham believes the story is “depressingly relevant 40 years on”.

“Obviously now it’s very different because we have almost record employment, but it’s as precarious as it ever was,” he says.

“Sometimes in Boys From the Blackstuff people had no jobs, and in the modern age sometimes people have three jobs – but they are still living with the economic pressures and the in-work poverty that these characters had, and the lack of hope.”

With the gig economy and cost of living crisis, the landscape “looks different, but it’s the same feeling, the same mood”, Graham says.

Today, Liverpool’s unemployment is much lower than the 80s but remains above the UK average, and official statistics say it is still one of the most deprived parts of the country.

Sloane hopes young Liverpudlians will come to see the play, and thinks they will recognise what Yosser, Chrissie, Loggo, George and Dixie went through.

“How can they not see themselves in this? Nothing’s really changed,” he says. “It should not be relevant. You should not be able to go, oh yeah, there’s people in the city and cities all around the country who can’t afford food for their children.

“We’re still feeling it. It’s right there and it’s right there and it’s right there,” he says, gesturing at different points in the city from the bench outside the rehearsal room.

“We should be screaming as loud as this piece is. It’s a punk piece, and I don’t see enough anger.”

Before long, the moustache goes back on, the rehearsals resume, and Yosser Hughes rises again.

Boys From the Blackstuff is at Liverpool’s Royal Court theatre until 28 October.