Artist’s Rooms at Jameel Arts Centre: Pushing the language of painting

“The Artist’s Rooms at Jameel Arts Centre is a kind of capsule show where we have the opportunity to collaborate with artists that are already part of the Art Jameel collection and commission new works,” says Nadine El Khoury of the show at Jameel Art Centre in Dubai, in an interview with Al Arabiya English.

“The three artists — Ayesha Sultana, Daniele Genadry, and Risham Syed — in this iteration of Artist’s Rooms have a making practice and are interested in pushing the language of the painting in their work.”

Both Ayesha Sultana and Daniele Genadry have newly commissioned works at the exhibition.

“Daniele developed a new series of paintings Shimmer, as well as a series of drawings that are studies of water shimmer, mountains, and a FraAngelico mural ‘Annunciation,’ which was the starting point for the wallpaper we covered all four gallery walls with. We also built a circular structure where the paintings were hung. Daniele’s intention was to create two different atmospheres each with a different lighting to create the experience of an ‘apparition’ or a sense of presence,” said El Khoury.

The curator said it was a great experience working with these female artists interested in pushing the boundaries of what painting and material practice can achieve. The three also “work in different contexts, which translates into the sensibility of their work.”

Daniele Genadry

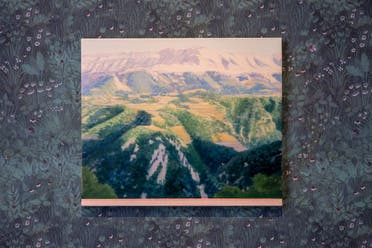

This Artist’s Room in Gallery 3 is anchored around Paris and Beirut-based multimedia artist Genadry’s major painting ‘Blind Light’ (2017), with new works based on her recent research in la Rochelle, France, and the Grand Canyon, USA.

Genadry is an assistant professor of studio arts at the American University of Beirut.

She focuses on distance, light, and movement and how they combine to affect visual experiences. Her practice focuses on the relationship between painting and photography, exploring the potential of an image to generate its own temporality.

Genadry spoke to Al Arabiya English on the various strategies she has used in her latest work being shown at Jameel Art Centre, besides the artistic influences, and theories from which her artistic impulses and practice emerge.

“This project arose out of my interest in apparitions as experiences that juxtapose two usually distinct dimensions: the natural and the supernatural, and generate a heightened perception. I wanted to think about apparitional vision as a perceptive mode that combined an awareness of two things at once – the material, physical reality and the immaterial or imaginary, like a delicate floating vision. The form of the encounter, rather than directly with an angel or ghost, is an intensified vision resulting from an awareness of beauty, or of precarity, which leads to the shock of presence. I also thought of apparitions as events that create particular spaces and times. The transformation of a background or of passing time into significant ground or stilled, concentrated time, is an operation that I attribute to apparitions, and one which I wanted to try to do through painting. For a painting to be able to act as an apparition, it would have to hold attention and interrupt the normal flow of time in order to create an experience that absorbed and held a person in a contemplative, durational state.”

Thinking about this, Genadry “revisited Fra Angelico’s ‘Annunciation’ in San Marco. The painting suggested a structure for an apparition quite different from its narrative representation. It combined physical elements, such as the architecture of the space in which it was painted; blotches of paint; and shiny flakes that reflect light, into the painting, and by doing so, juxtaposed the painted space with the actual one. This confusion of the present context and painted image charges the space with a sense of presence.”

She recalls that her work began “with photos of landscapes, some well known and others new, whose images suggested to me a possible flip or transformation, where the landscape could open up — into a field of shimmer, a blinding glow, or a fading fragile image — and could also reflect the conditions of how and where it was seen. I painted these lightly, and in such a way (fluorescent, monochromatic paint, alternating surface texture) that they interacted strongly with their environment—such as the ambient light conditions of the room where they were seen– combining actual light qualities with those which seemed to be coming from the painting itself.

The space was imagined as one where you could literally enter into a painting — walk in and around it, find different elements of framing and representation and engage with different moments of stillness or vibration. I thought of the installation as a three dimensional painting, as a way of capturing not only the eye and peripheral view as in the paintings when taken by themselves, but as a way of enveloping the whole body—allowing the body to move from part to part — drawn to elements in one corner, a color glow in another, entering the circle from one position, exiting, and entering from another—in short, I wanted to create an embodied experience of what it would be like to look long and fully in a painting, to become part of it, and in particular — using Fra Angelico as a model — to use the apparitional structure, so that the whole experience might result in a sense of expanded time and space, stillness and presence.”

Most of Genadry’s works deal with themes of light, ways of seeing, as well as the relationship between painting and photography.

How does this approach vary when the subjects and physical locations changes – from Europe, to Lebanon, and then to the US at the Grand Canyon?

“As the subject and physical location that I use to create the work is not the content of the work, the approach does not depend on them, but rather on what I am trying to examine or understand in a particular project. In this installation, I used landscape and painted images as sources in order to find ways of painting light — that I was trying to make present and intensify in each painting. In the circular space the three paintings each try to capture a different quality of light/perception: A blinding glow, a tenuous or fading image, and a shimmering or vibrating light. The landscapes are taken from three different continents and are not specified in the titles — and what was important for me was how certain images or geographies provided hints on possible pictorial strategies that would create the sensation of a certain quality of light, or perceptive experience in the most intense or affective way. One such source image was a photograph by Muybridge, where a waterfall became an empty space on the image, as a result of the camera not being able to capture the moving water. This provided an idea of how to create a glow…the shock of the white blank area that ‘ruined’ the photograph, provided a clue as to how to create a sense of glowing light: framing an empty white space on the canvas with slight representative elements, such as in the painting ‘Blind Light.’”

Genadry said that in her work, “I try to create an awareness of the local conditions of sight and to activate a different perspective mode, more conscious, sensitive and embodied. I use landscapes or photos that I have seen or found, where I detect a possibility — or an opening — to reveal a force — like a dematerializing light. In this sense, the paintings do not represent a place, identity, or narrative — they attempt to create a perceptive experience that is only accessible in the present tense: in the actual act of looking at the painting in the space where it is. I think this approach — foregrounding the act of looking — gives the viewer an agency and a consciousness, which results from being aware of all the conditions of their sight: the kind of space, their physical position, the ambient light, the effect of the painted image on their eyes, etc. This way of consciously looking, with attention and time, is an attempt to reclaim sight and agency, from the dominant modes of vision that oppressive ideologies produce and use to create a blind, distracted, and powerless sight.”

Genadry confirmed her familiarity with David Hockney’s work “A Bigger Grand Canyon” and said she has been working on a project in collaboration with the Grand Canyon National Park and the Grand Canyon Conversancy where I am creating a piece that is in conversation with Hockney’s paintings of the canyon

“And I am interested in the issues of perspective that Hockney thinks about — such as those in a video interview on the Louisiana Museum channel, where he speaks about the difficulty of capturing the canyon in a photographic image, and how the experience of being on the edge, is one which allows and requires a kind of meandering eye/gaze, looking near and far, here and there, constructing the visual slowly and accumulatively, as it is too vast and present to be captured in a photographic still image, which tends to insert a distance into the view.”

Genadry said the kind of painting that I propose is different, in that it tries to combine an immediate image (one that is seen all at once, like a glimpse) with a kind of mesmerizing or hypnotic attention, where the viewer keeps looking at and around the image because it is not really graspable — it is tenuous, even while being present.

Risham Syed

The exhibition in Gallery 2 comprises Lahore-based artist Risham Syed’s major installation ‘The Seven Seas’ (2012), a series of large-scale quilts depicting 20th-century maps of various port cities that were strategically located on the colonial European trade route –- including Ras al-Khaimah, UAE; Izmir, Turkey; Kandy, Sri Lanka, among others.

The artist connects the intricacies of contemporary geopolitics with the 19th and early 20th Century cotton trade of the British Empire, with the work itself created from fabrics sourced during her travels to Turkey, Bangladesh, the UAE, Sri Lanka, UK, India, and within her native Pakistan.

Risham’s practice focuses on the remains of cultural and historical inheritance and its perceived authenticity in present-day Pakistan.

The series ‘The Seven Seas, (2012) connects the intricacies of contemporary geopolitics with the 19th and early 20th Century cotton trade of the British Empire.

While rooted in the history of colonialism, trade, supply chains, and exploitation of natural resources and labor, her work points to remnants of these forces at play even in the 21st Century.

When asked what has been the dominant viewer response to your major work ‘The Seven Seas’ (2012), ever since it was unveiled, that artist sayid: “I would like to quote the text that I wrote out in 2012 when I made this work:“The Seven Seas (2012) 7 Cotton Quilts filled with synthetic American wool MENASA region (Middle east, North Africa and South Asia) is linked through British rule in the 20th century. Studying this region, there is a strong link of trade and exchange that resulted in sharing a political and geographical history.”

“The 20th century saw the British Empire thrive on this trade. Raw material like cotton, jute, tobacco, dyes, spices were taken away from the colonies. English people bought Indian cotton in the field, picked by Indian labor at a nominal wage. This cotton would be shipped on British ships to London. Opening of the Suez Canal shortened this trip drastically. Great Britain took control over Egypt in this process. Military garrisons were established in ports of the British Empire as strategic sights along the Great Maritime Route. Cotton would be turned into cloth in Britain and the finished product would be sent back to India at European shipping rates, once again on British ships. And then cloth finally sold back to the kings and landlords of India who had the money to buy this expensive cloth. Through the project ‘The Seven Seas’ this process is investigated and how even after a century we are still a part of the same larger network of forces at work. Within each quilt of the Seven Seas, a tale of rebellion associated with each particular port of trade is woven in.MENASA accounts for 24 percent of today’s global hydrocarbon production and so economically and politically this is a strategic region.”

“I probe history through material tied up with trade, power, class and culture, hence smeared with violence, drudgery, upheaval and turmoil. Objects, materials, textures, seals and patina tell us about time, history, memory, emotions ,and their connection with the present moment.”

Asked about Lahore-based art critic Quddus Mirza’s eloquent summing up of her oeuvre, in a review of her exhibition that “we- – including Risham Syed – have disappointments with history,” the artist responded: “Quddus Mirza has indeed summed up my concerns well. The work I presented in ‘Appointments and Disappointments with History’ in September 2022 was a continuation of the ‘Seven Seas’ from 2012. While tracking banal objects ordinarily found in Punjabi-Victorian homes, I stumbled upon the rise, fall, and merger of giant companies like Johnson Brothers and British Home Stores that have their roots in the colonial ventures of the 18th/19th centuries. I collected objects from the Landa Bazaar in Lahore (Landa referring to London) where traditionally second-hand objects end up from England to cater to the local market. I juxtaposed these with the quilts (quilts had world maps from history). Tracing the history of and rise and fall of these giants (companies these objects came from) I connected these objects with industrialization, capitalism, environment, and global warming. From my text for this body of work, ‘here in these works I present a conversation between these objects, materials, space and time and the present moment in which nature is almost ready to exit.’”

Ayesha Sultana

Ayesha Sultana, brings together recent works on paper and in Gallery 1 exploring her longstanding engagement with the materiality and everyday iconography of her home city of Dhaka, rendering forms of street corners, architectural features, wall textures, and construction detrius encountered during her day-to-day life.

These impressions accumulate in her subconscious and find themselves on paper. They are not just observations of form, but of material, movement, and distance; key aspects that have held Sultana’s interest over time.