‘This history mustn’t be forgotten’: The real story behind the Nuremberg trials

The Nazi high command was put on trial 80 years ago in 1945. In the new film Nuremberg, starring Russell Crowe as the charismatic and manipulative Hermann Göring, director James Vanderbilt draws on a little-known chapter of the trial’s proceedings to ask enduring questions about the wellspring of fascism and the true nature of evil.

A criminal trial is inherently dramatic, often full of revelatory testimony, sparring lawyers, and stern pronouncements from the bench. Little wonder that so many powerful films and TV series are set in the courtroom: Inherit the Wind, To Kill a Mockingbird, A Few Good Men, and Presumed Innocent, to name just a handful. And every trial provides a denouement – the verdict – which determines guilt or innocence, and naturally engages the audience’s own sense of right and wrong.

But the trial that began in Nuremberg, Germany, late in 1945, just a few months after the end of World War Two, stands apart. In an unprecedented attempt to hold individuals responsible for war crimes, the Nazi high command was brought to that bomb-shattered, rubble-strewn city to appear before a military tribunal.

Although some on the Allied side – the US, the UK, France and the Soviet Union – believed summarily shooting the Nazi leaders was the simpler option, a decision was taken to grant these men their day(s) in court. The tribunal’s prosecutors and judges bore a huge responsibility to act fairly, as many Germans perceived the trials as nothing more than vengeful “victor’s justice”.

This potent history has inspired film-makers before – most notably Stanley Kramer, who produced and directed the Oscar-winning classic Judgment at Nuremberg starring Spencer Tracy in 1961. A well-received two-part docudrama called Nuremberg, starring Alec Baldwin, was broadcast in 2000 on TNT in the US and the CTV television network in Canada.

A quarter of a century on, writer-director James Vanderbilt, best known for scripting Zodiac and The Amazing Spider-Man, has revisited the famous trials. As he explained on 5 October from the stage at the Hamptons International Film Festival, where his film Nuremberg was screened for the first time in the US, “this history mustn’t be forgotten”. Growing up, Vanderbilt, now 50, had been aware of Nazi crimes – the events were relatively recent. But for his own daughter and her peers, the stories are “distant, and almost unreal”.

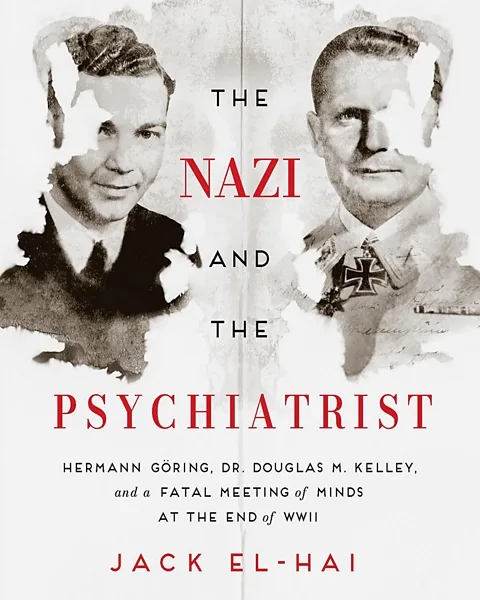

Vanderbilt found his angle upon reading The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, a book by journalist Jack El-Hai about Hermann Göring and the young army psychiatrist tasked with determining the mental competence of the accused Germans slated to stand trial at Nuremberg.

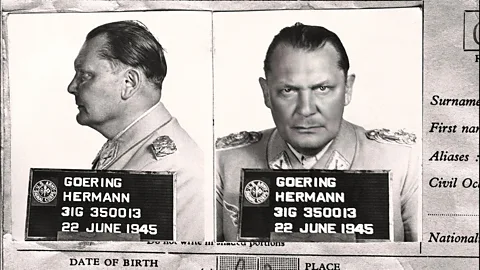

The flamboyant Göring, Hitler’s second in command, was a flying ace in World War One who became a big man, nearly 300lbs. He’d been photographed in innumerable different uniforms, often carrying an ivory baton, studded with diamonds, presented to him by Hitler to designate his unique rank as Reichsmarschall. Göring was the most senior of the 22 prominent Nazis captured by the Allies – many others had killed themselves or vanished.

On 9 May 1945, soldiers of the US Seventh Army near Salzburg, Austria, encountered Göring, driving in a convoy of cars, accompanied by an entourage: his wife, young daughter, other relatives, servants and military aides. From the start, as shown in Nuremberg, the notorious Nazi leader fascinated his captors – they gawked at him, asked for his autograph, and chatted with him in English (he spoke the language fairly well).

The Nazi and the psychiatrist

Soon, however, Göring was separated from his family and flown to Bad Mondorf, in Luxembourg, where the US Army had refitted a large hotel to serve as a stockade to imprison the top Nazis.

They weren’t buddies – but they formed a connection, and Kelley recognised that they shared certain personality traits – Jack El-Hai

It was there that the psychiatrist, Douglas M Kelley, spent hours interviewing Göring, and administering psychological tests. Kelley quickly discovered that the former Reichsmarschall was addicted to paracodeine, a painkiller, popping dozens of pills a day. He helped Göring break that addiction and lose weight.

“They weren’t buddies,” author El-Hai tells the BBC. “But they formed a connection, and Kelley recognised that they shared certain personality traits.” As well as acknowledging Göring’s charm and intelligence, the doctor noted his drive, his defiance, his enormous ego, and his intense loyalty to family and country.

The doctor’s own ambition was to identify among the Nazis a shared psychosis or particular derangement, because only that, he believed, could account for their monstrous acts. Yet after intense study, Kelley conceded the men were fundamentally opportunists who had grabbed the chance to exercise power and exploit others. “And he concluded there have always been people like this, although the atrocities they commit are much smaller,” says El-Hai.

Rami Malek, in the role of Kelley, and Russell Crowe, playing Göring, have excellent onscreen chemistry. The audience watches the pair converse, jousting and joking, and coming to trust each other. Göring enlists Kelley’s aid to communicate with his wife and daughter, and the doctor, defying protocol, hand-delivers letters to them for Göring.

During one exchange with Kelley, included in the book but not the film, Göring tells the doctor he fears that he and his wife will both soon be dead, and asks the doctor to adopt their seven-year-old daughter Edda, and raise her in America. While Kelley did not record how exactly he replied, El-Hai wrote: “This astonishing request – a sign of Göring’s respect for Kelley – moved the psychiatrist, who knew how much Edda meant to her father.”

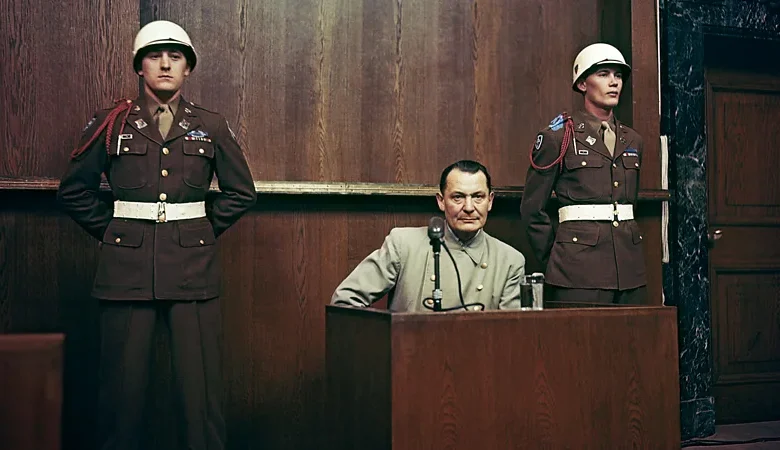

The more conventional second half of Nuremberg takes place in court. In testimony closely adhering to the actual transcripts, Crowe, as Göring, launches a vigorous defence laced with self-effacing repartee, and manages to wrong-foot the US chief prosecutor, Robert H Jackson (played by Michael Shannon). The British lawyer Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe (Richard E Grant) has greater success by using incriminating documents to establish the former Reichsmarschall’s direct responsibility for the persecution of Jews. Shocking film shot by the Allied soldiers who liberated the concentration camps is then screened, as actually happened at Nuremberg. Göring looks away as emaciated figures and piles of bodies appear in flickering black-and-white.

True scale of the crimes

The graphic film of the camps was a turning point in the trial, bringing the horror of the Holocaust directly into the courtroom. “Eisenhower had insisted that the camps be filmed,” Dr Thomas Schwartz, professor of history at Vanderbilt University, tells the BBC, speaking of the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. “And the Russians made films, too. These were extraordinarily effective in conveying the true scale of the crimes.”

Göring was among those Nazis sentenced to death by hanging, but he took his own life the night before his scheduled execution by killing himself with cyanide. In the film, how he managed to obtain the capsule is left unexplained. A 2005 confession by a US prison guard offers one plausible answer. The guard, Herbert Lee Stivers, recounted how a German girl he’d met called Mona fooled him into passing Göring a small glass vial she said was medicine, and subsequently disappeared.

But Göring himself left a note for the prison commander saying that none of the guards was responsible, and that he had smuggled the cyanide into his cell in a jar of hair cream and then hidden it. In another note, Göring claimed he would have allowed the Allies to execute him by firing squad, “a soldierly death”, but he refused to accept the humiliation of being hanged.

In Vanderbilt’s film, the final word is not Göring’s, but given to a young sergeant, Howard Triest (played by Leo Woodall), who acted as one of Kelley’s translators. Triest, born into a German Jewish family in Munich that relocated to the US, had many relatives who perished in Auschwitz. In the scene when Kelley is departing Germany for home, Triest says: “Do you know why it happened here? Because people let it happen.”

The question of collective national guilt was one that Kelley pondered for years afterwards, according to El-Hai. “And he was on guard back in the United States for incipient fascism. He was suspicious of politicians, especially populists in the south who played on racial segregation to assemble power.”

Kelley wrote a book about his experiences with the Nazi defendants, titled 22 Cells in Nuremberg, and lectured widely. Yet his post-war life disappointed him. His book failed to sell well, and despite relentless work as a teacher, doctor, criminologist and police consultant, he never succeeded professionally to the extent he felt he should. He began to drink too much. When his wife advised seeking help from a fellow psychiatrist for his often low and angry moods, he rejected that idea as undermining of his own authority as an expert on mental health.

Aged 45, on New Year’s Day 1958, after a loud argument with his wife and in front of his son and his father, Kelley dramatically swallowed cyanide, killing himself in the same way Göring had, a sad end for a psychiatrist who sought earnestly to understand men who committed sickening crimes.