‘It becomes more about status signalling’: Is £7m for a handbag absurd or justified?

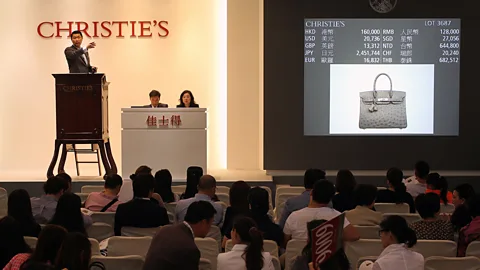

As a pop-up handbag auction opens in London, a fashion frenzy is gripping venerable auction houses – and sending prices sky high. Can fashion ever be on a par with a Picasso?

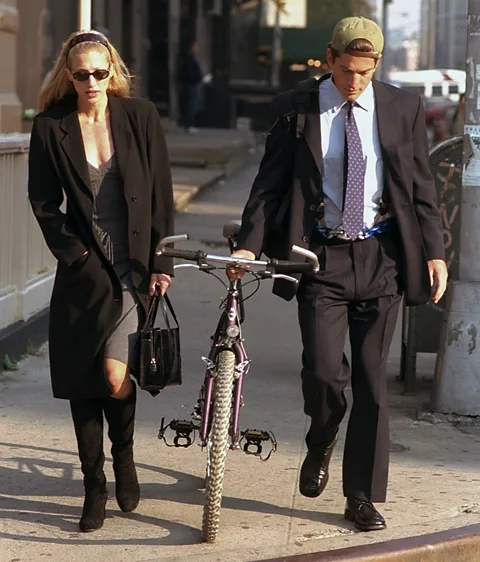

“I like my money where I can see it. Hanging in my closet,” says Carrie Bradshaw in the 2000s TV series Sex and the City, and it would appear that an increasing number of collectors do, too, with archival fashion auctions fetching record prices. Just last month, Sotheby’s auction house in Paris sold a battered Hermès bag owned by its namesake, Jane Birkin, for £7m ($9.2m). And now Sotheby’s in London has just opened a luxury pop-up salon, auctioning pieces by Hermès, Rolex and Cartier, running until 22 August.

But it wasn’t always like this. Many auction houses have traditionally viewed their fashion divisions as tangential, with the brand-name recognition of some of the items drawing buyers in, and towards bigger-ticket items like paintings or sculptures.

Shouldn’t clothing be worn? Jane Birkin certainly had no qualms about using her Hermès bag

Clothing belonging to celebrities, like Princess Diana or Marilyn Monroe, have historically fetched more than garments without a celebrity provenance, though nothing quite like the £7m Birkin bag. Monroe’s infamous “Happy Birthday Mr President” dress, known as the world’s most expensive dress, sold in 1999 for $1.3m, and again in 2016 for $4.8m to Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Museum. It currently resides there when it’s not being taken for a spin by Kim Kardashian, who wore it to the 2022 Met Gala. Cora Harrington, fashion historian and author, says the dress’s association with Kardashian will likely increase the value the next time it comes up for auction, despite any wear and tear caused by the star.

“I think that would have been true regardless of whether Kim wore it because it’s Marilyn Monroe, but there are enough fans of Kim Kardashian that would likely result in a higher price,” she said. “Usually when an object is damaged it would devalue it, but it’s the opposite in this case.”

Conversations around auction items online and in the media, whether positive or negative, influence the sale price. For example, the furore surrounding Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy’s costumes in the upcoming Ryan Murphy TV series American Love Story will be likely to escalate the value of the ur-influencer’s garments the next time they go up for auction.

The real deal

Modern-day influencers are also swaying how we think of luxury fashion, including the online communities dedicated to finding the best dupes, which Harrington says has added more value to the real thing – and created more work for luxury authenticators.

Then there’s the popularity of resale sites like Depop, Vinted, eBay, Vestiaire Collective and TheRealReal lowering the barrier of entry to the luxury market.

It becomes less about fashion as creative or social expression and more about status signalling and speculative investment – Usha Haley

“Dupes have driven more people to buy authentic,” says Michael Mack, president of Max Pawn Luxury, which has one of the largest collections of Hermès bags for sale in the US. “It’s not just Gucci, Hermès or Chanel; we sell Coach, Michael Kors and Kate Spade. Those are $300, $400, $500 bags and we do big business in that.” And it’s not just big-ticket items like the $180,000 and $240,000 Himalayan albino crocodile diamond-encrusted 25cm Birkins he’s sold to celebrity clients, Mack adds.

Could resale’s democratisation of luxury be in turn driving up these auction prices? Usha Haley, W Frank Barton Distinguished Chair in International Business at Wichita State University, Kansas, thinks so. “If investors begin flipping [buying then quickly re-selling for profit] items purely for short-term gain, it could destabilise the market and drive prices to be unsustainable,” she said. “The rising value of archival pieces may further detach fashion from everyday people, turning symbols of culture and identity into ultra-exclusive status objects out of reach for most, even as fashion becomes more democratised in digital spaces.”

Meanwhile, social media is exposing new audiences to style icons from the past and historical garments featured in the annual Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute exhibition, kicked off by the Met Gala, which this year brought in record profits.

This brings up the argument that items of such delicacy and historical relevance should be in a museum – one with stronger collection, conservation and loan policies than Ripley’s. It’s a valid one, to be sure, but just because an item is acquired by a museum doesn’t mean it will necessarily be accessible to the public, as the majority of pieces in most institutions are not on display.

“There are services [that care] for private collections that are on the same level or even better than museums,” Harrington says, pointing to companies such as Uovo. But shouldn’t clothing be worn? Jane Birkin certainly had no qualms about using her Hermès bag, its battered state causing as many headlines as – and comparative to – its sale price. The experts I spoke to agreed.

“There’s a collectable function, but the point of clothing is to wear it,” Harrington says. “Wear it. Use it. Enjoy it,” Mack concurs. “I think you see more people wearing these luxury items, and not so much of the collectability [aspect].”

The very nature of an auction is the thing is worth what someone is willing to pay for it – Cora Harrington

They are also in agreement about the notion that fashion is wearable art. According to Harrington, the argument that fashion is not art – and therefore shouldn’t be fetching high prices on par with a Picasso – is rooted in “larger structural conversations around misogyny and women’s work and the fact that when women are interested in things they must be inherently less valuable”.

Viewing fashion and art as commodities concerns Haley. “The escalating prices become less about fashion as creative or social expression and more about status signalling and speculative investment,” she says. “Auctions then can sideline the deeper cultural conversations that fashion artefacts could inspire – about sustainability, labour, craftsmanship, or even the identity of the women who made them famous.”

Arguably, decades of experience on the part of designers, centuries of establishment for houses like Hermès, which launched in 1837, and the many hours of craftsmanship that go into these pieces is what people are paying for. The Jean Paul Gaultier denim and ostrich feather gown from the 1999 spring couture collection – that sold for €71,500 (£61,900) last year – springs to mind. In the end, says Harrington, “the very nature of an auction is the thing is worth what someone is willing to pay for it. If a dress sells for $300,000, then the dress is worth $300,000.”