‘Bring hard justice’: Liberia civil war survivors welcome war crimes court

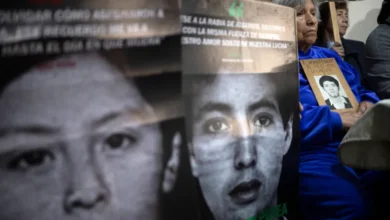

Rufus Katee, 60, remembers Liberia’s civil wars well.

It was July 1990 when the then-26-year-old ran to escape the fighting between armed groups and soldiers in the capital, Monrovia. He fled to St Peter’s Lutheran Church in search of safety.

“There were a lot of civilians who took refuge in the church. But I didn’t know I was going for my suffering,” Katee said, recalling the harrowing events that followed.

“Soldiers came to the church in the night and started shooting. Once it started, I dropped to the floor, but the people they killed were dropping over me, and they covered me. That’s how I survived,” he told Al Jazeera.

Katee broke his hip in the attack and, decades on, still suffers pain because of it.

An estimated 600 people were killed that night, and many more survivors suffered physical and mental injuries that have lingered for years.

The attack was just one of thousands that took place during Liberia’s two civil wars from 1989 to 2003, years of untold violence during which a quarter of a million people were killed.

Numerous other atrocities also took place, including rape and sexual violence, mutilation and torture.

Much of the violence was perpetrated by rebels as well as the Liberian army and militias that included child soldiers.

Yet, decades on, Liberia has not prosecuted anyone for the crimes and rights violations that took place.

War crimes court

Last month, President Joseph Boakai issued an executive order establishing the office of a war crimes court.

Many welcomed the move, which they said was long overdue. However, others are concerned it could reopen old wounds and raise tensions after compromises were made to secure peace.

The lack of prosecution of perpetrators for 21 years has largely been a result of a lack of political will, experts told Al Jazeera, which is partly due to the influence of individuals who were involved in the wars and who now wield political power.

At the end of the civil wars, slots in Liberia’s interim government were divided among warring factions who inserted their members or proxies in these positions.

Additionally, political alliances have become integral in Liberia’s elections because the political system requires an absolute majority to win the presidency. As a result, every post-war president has since allied with influential figures, many of whom took part in the wars.

“Liberia’s delay in prosecuting its war criminals is due in part to political will and the complex nature of power-sharing,” explained Aaron Weah, a Liberian doctoral candidate at Ulster University’s Transitional Justice Institute.

“The 2003 peace agreement signed in Accra that helped bring an end to the war gave political power to people that were fighting. When elections came as well, the government had these former war actors in power, so it was difficult for them to prosecute themselves or implement the 2009 TRC [Truth and Reconciliation Commission] recommendations,” he said.

Conmany Wesseh, a former senator, minister and civil society leader, was involved in negotiating the 2003 peace agreement.

“During negotiations for the peace deal to end the war, we weren’t making progress because the warring parties did not want to sign the peace agreement,” he told Al Jazeera. “It was only when we agreed that the way to go was a truth and reconciliatory commission as used in South Africa [after apartheid ended] instead of a war crimes court, that was when they signed.”

“There was no victor,” he added, “there was a peace agreement that allowed for compromises so as to stop the war and the killing, and this has allowed us to keep the peace for 21 years.”

Palava huts

In 2005, the Transitional Legislature at the time established the TRC of Liberia with a mandate that included investigating human rights abuses committed during the war, providing a forum to address issues of impunity, and recommending measures to be taken for the rehabilitation of survivors in the spirit of national reconciliation and healing with the objective of promoting national peace, security, unity and reconciliation.

In 2009, the TRC issued its final report, recommending the establishment of an Extraordinary Criminal Court for Liberia to try gross human rights violations, reparations for victims, and disbarring certain individuals from holding office, including Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the president at the time.

The court, however, was never established despite campaigns from civil society and promises by previous governments.

Instead, the country has settled for non-prosecutorial forms of justice through its National Palava Hut programme, which provides a space for victims and perpetrators in a community to interact with one another and for perpetrators to ask for forgiveness.

Palava huts, though, are not recognised courts, and no punishments are handed down. The hearings are also restricted to lesser crimes, which include arson, assault, forced labour, looting, destruction and theft.

As a result, victims seeking justice have turned to courts in Europe and the United States that have prosecuted and sentenced a small number of former strongmen who relocated abroad. These individuals are usually tried for war crimes under universal jurisdiction or immigration fraud in instances when they omit their alleged war crime history from immigration documents.

Concrete steps

However, things are changing after Liberia’s Legislature in April passed a resolution calling on the president to establish two courts: a war crimes court and an economic crimes court.

To the surprise of many, this resolution was signed by some former rebels who took part in the war and had previously opposed the establishment of a court.

It was based on this that Boakai in May issued his executive order for the establishment of the Office of War Crimes and Economic Crimes Court.

The office is tasked with investigating and designing the methodology, mechanisms and processes for the establishment of a Special War Crimes Court for Liberia and a National Anti-Corruption Court. It is also tasked with recommending a way to source funds for the court’s operations.

And while there is no stated timeline for the establishment of the war crimes court, the establishment of an office is Liberia’s most concrete step thus far towards domestic prosecution of its war criminals, and it has been largely celebrated, especially by victims, the international community and civil society who campaigned for its establishment.

‘Establish the court now’

Peterson Sonyah, who heads the Liberia Massacre Survivors Association, is one of those pleased about the developments.

Sonyah was 16 in 1990 at the time of the Lutheran church massacre that he, like Katee, also survived. He remembers that night vividly.

“It was in the night, but the guns lit up the church hall like it was broad daylight,” he told Al Jazeera. “I and my father had gone to Lutheran for refuge. That’s why we were there. The church used to give us food.

“When the soldiers started shooting, he covered me with his body, but one bullet went in his arm and another in his hip. In the morning, he said he was thirsty. I went to get him water, and when I came back, he was dead. I lost seven family members at Lutheran.”

Now as an adult still living with the weight of all he lost, Sonyah said he is “happy” about the news of a future war crimes court.

“I support the court 100 percent. I have been campaigning for this court since the time of the TRC. We need the court to address impunity and for people to pay for their crimes, so they need to establish the court now.”

His stance is echoed by Hassan Bility, the executive director of the Global Justice and Research Project, a Liberian NGO that campaigns for the court’s establishment and the international prosecution of war criminals.

“The signing of the executive order by President Boakai is an encouraging development. At least it indicates his administration’s willingness to do something about our wartime atrocities,” he said.

“When the soldiers started shooting, he covered me with his body, but one bullet went in his arm and another in his hip. In the morning, he said he was thirsty. I went to get him water, and when I came back, he was dead. I lost seven family members at Lutheran.”

Now as an adult still living with the weight of all he lost, Sonyah said he is “happy” about the news of a future war crimes court.

“I support the court 100 percent. I have been campaigning for this court since the time of the TRC. We need the court to address impunity and for people to pay for their crimes, so they need to establish the court now.”

His stance is echoed by Hassan Bility, the executive director of the Global Justice and Research Project, a Liberian NGO that campaigns for the court’s establishment and the international prosecution of war criminals.

“The signing of the executive order by President Boakai is an encouraging development. At least it indicates his administration’s willingness to do something about our wartime atrocities,” he said.

‘We made compromises for this peace’

Not everyone agrees with the establishment of the court. Critics have expressed concerns about the security implications of prosecuting now-powerful former warlords who have considerable support, while many have argued that public funds for a court would be better put towards improving the livelihoods of Liberians.

“Whatever we do that could lead to the war, we should reject,” Wesseh said. “We made compromises for this peace. We must not do anything to reverse these gains in peace, and I don’t believe the way to consolidate this peace is a war crimes court.

“Instead, to solidify our peace, we must make sure the courts and hospitals are working and people have jobs.”