What is the UN High Seas Treaty and why is it needed?

After more than a decade of negotiations, the countries of the United Nations have agreed the first ever treaty to protect the world’s oceans that lie outside national boundaries.

The UN High Seas Treaty places 30% of the world’s oceans into protected areas, puts more money into marine conservation and means new rules for mining at sea.

Environmental groups say it will help reverse biodiversity losses and ensure sustainable development. Here’s what you need to know:

What are the high seas?

Two-thirds of the world’s oceans are currently considered international waters.

That means all countries have a right to fish, ship and do research there.

But until now only about 1% of these waters – known as high seas – have been protected.

This leaves the marine life living in the vast majority of the high seas at risk of exploitation from threats including climate change, overfishing and shipping traffic.

Which marine species are at risk?

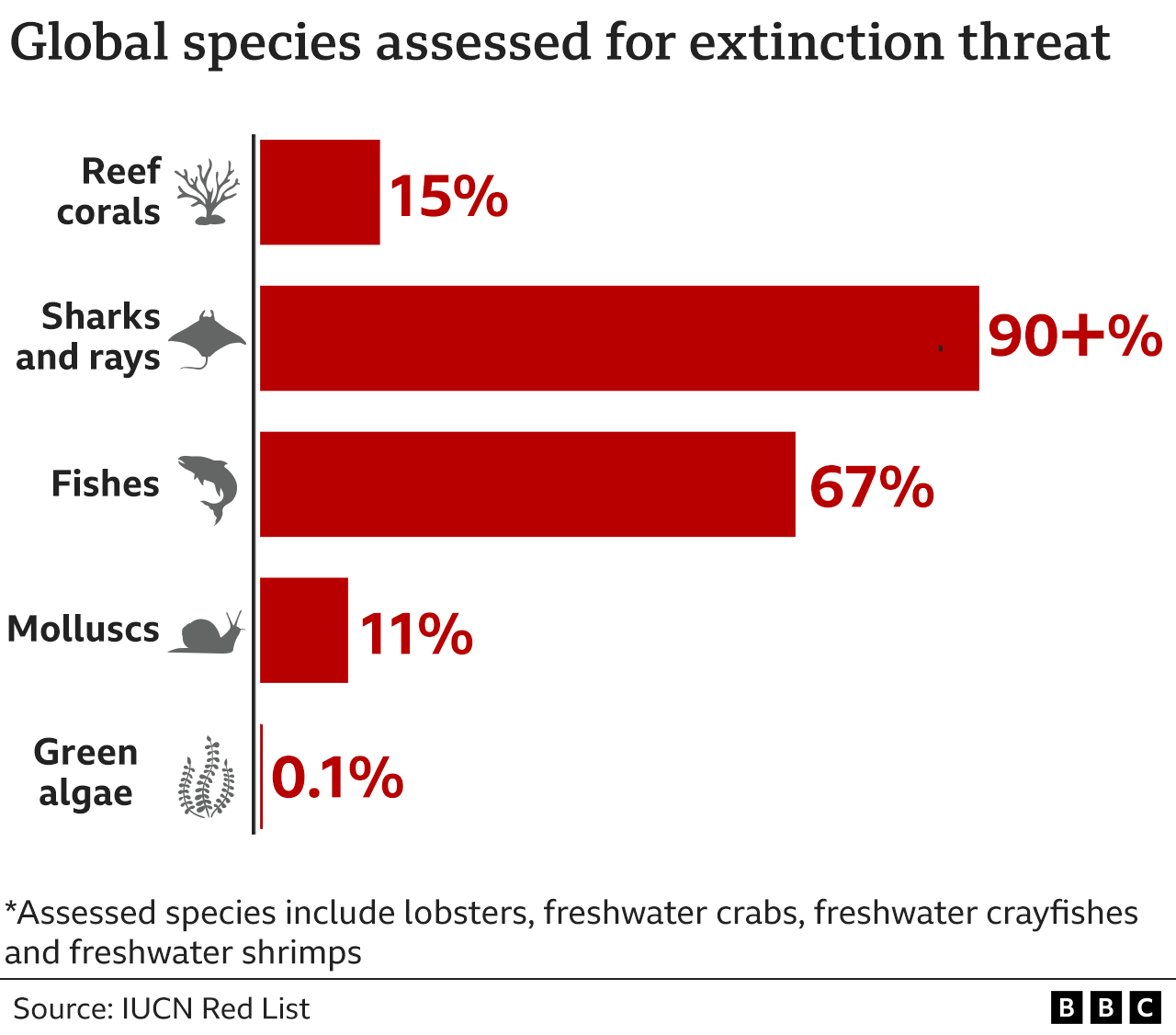

In the latest assessment of marine species, nearly 10% were found to be at risk of extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Dr Ngozi Oguguah, chief research officer at Nigerian Institute For Oceanography and Marine Research said: “The two biggest causes [of extinction] are overfishing and pollution. If we have marine protected sanctuaries most of the marine resources will have the time to recover.”

Abalone species – a type of shellfish – sharks and whales have come under particular pressure because of their high value as seafood and for drugs.

The IUCN estimates that 41% of the threatened species are also affected by climate change.

Minna Epps, head of IUCN’s ocean team, said: “A bit more than a quarter of emitted carbon dioxide is actually being absorbed by the ocean. That makes the ocean much more acidic, which means that it’s going to be less productive and jeopardize certain species and ecosystems.”

Climate change has also increased marine heat waves 20-fold, according to research published in the magazine Science – which can bring about extreme events like cyclones but also mass mortality events.

Ms Epps said to tackle the issue of climate change in the sea involves implementing the other global agreements such as the Paris Agreement.

She said: “This is a real reason to have a synergies and collaboration between these different multilateral agreements we’ve seen increasingly within the UN conventions on climate change.”

The treaty also aims to protect against potential impacts like deep sea mining. This is the process of collecting minerals from the ocean bed.

Environmental groups are seriously concerned about the possible effects of mining, such as disturbing sediments, creating noise pollution and damaging breeding grounds.

What is in the High Seas Treaty?

The headline is the agreement to place 30% of the world’s international waters into protected areas (MPAs) by 2030.

However, the level of protection in these areas was fiercely contested and remains unresolved.

Dr Simon Walmsley, marine chief advisor of WWF-UK said: “There was debate particularly around what a marine protected area is. Is it sustainable use or fully protected?”.

Whatever form of protection is agreed, there will be restrictions on how much fishing can take place, the routes of shipping lanes and exploration activities like deep sea mining.

Other key measures include:

- Arrangements for sharing marine genetic resources, such as biological material from plants and animals in the ocean. These can have benefits for society, such as pharmaceuticals and food

- Requirements for environmental assessments for deep sea activities like mining

Richer nations have also pledged new money for the delivery of the treaty.

The EU announced nearly 820m euros (£722.3m) for international ocean protection on Thursday.

However, developing nations were disappointed that a specific funding amount was included in the text.

Will this make a difference?

Despite the breakthrough in agreeing the treaty there is still a long way to go before it is legally agreed.

The treaty must first be formally adopted at a later session, and then it only enters “into force” once enough countries have signed up and legally passed it in their own countries.

Dr Simon Walmsley said: “There is a real delicate balance, if you don’t have enough states it won’t enter into force. But also need to get the states with enough money to get the impact. We are thinking around 40 states to get the whole thing into force”.

Russia was one of the countries who registered concerns over the final text.

Countries have to then start looking at practically how these measures would be implemented and managed.

Ms Epps, from the IUCN said this implementation is crucial. If marine protected areas are not properly connected, it might not have the desired impact as many species are migratory and may travel across unprotected areas where they are at risk.