Welsh technology to join search for life on Mars

A scientific instrument built in Wales will lead the search for life on Mars at the end of this decade.

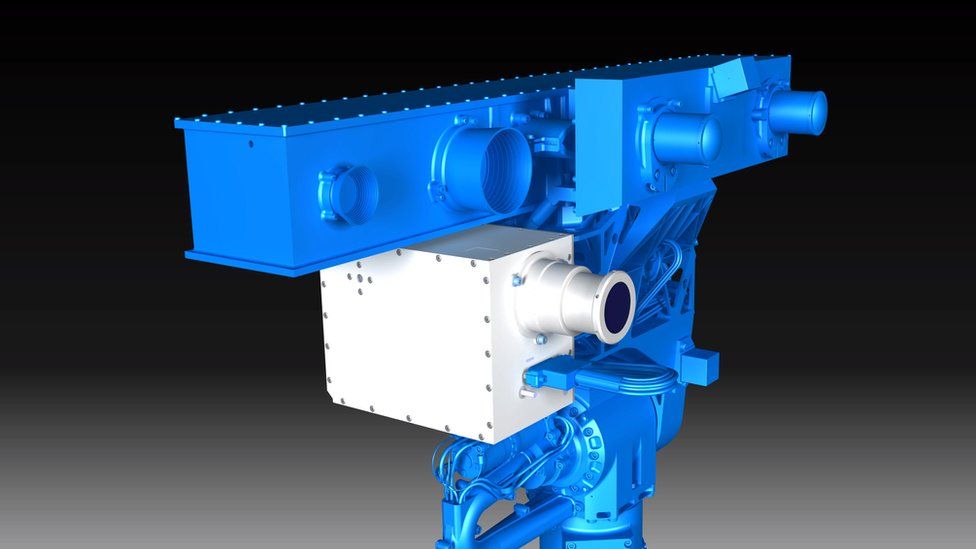

Enfys, meaning “rainbow” in Welsh, is an infrared spectrometer and will be assembled at Aberystwyth University.

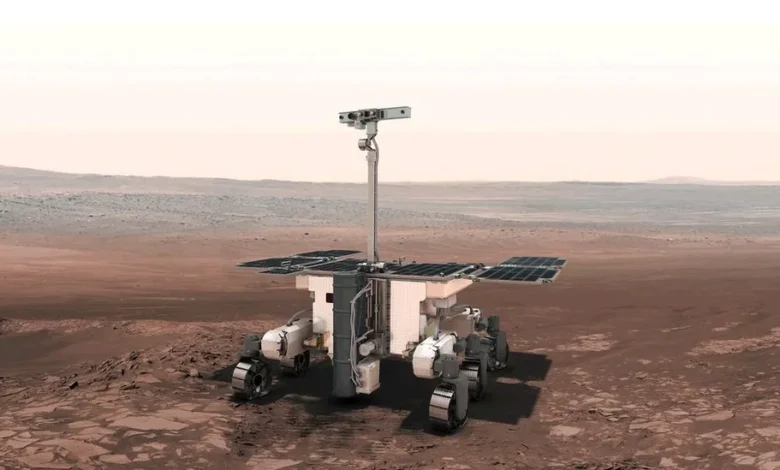

It will be fitted to the European Space Agency’s Rosalind Franklin rover, which launches to the Red Planet in 2028.

Enfys will work alongside the robot’s other camera systems to identify the most promising rocks to drill and test for evidence of ancient biology.

The development cost of £10.7m ($13.4m) is due to be announced by science minister Andrew Griffith at the UK Space Conference in Belfast on Thursday.

The Welsh spectrometer will be replacing an instrument from Russia.

Moscow had previously been a partner on the mission but all its hardware was offloaded from the rover by Europe’s space agency in protest at the war in Ukraine.

Enfys will be a direct replacement in terms of mass and volume but will carry a number of technical updates.

It will be hung from a mast holding the robot’s camera platform, called Pancam, working in unison with high-resolution and wide-angle sensors to survey the Martian landscape.

“We will take a picture with Pancam and get a spectral measurement from Enfys,” explained the university’s Dr Matt Gunn.

“This will allow us to work out what kind of minerals are in the rocks,” he told BBC News, adding: “We’ll be interested in the sorts of minerals that formed in wet environments, the kinds of environments that could potentially have harboured life.”

Rosalind Franklin is designed to do something no previous Mars rover has attempted, which is to drill and retrieve rock samples from more than a metre underground. It is thought any evidence of present or, more likely, past life will be found beneath the planet’s surface, away from the destructive effects of space radiation.

The six-wheeled Franklin robot was first approved way back in 2005. The project has since gone through a number of redesigns and funding crises. The fallout over Ukraine is just the latest setback and means the mission will not get to the launchpad for another five years now.

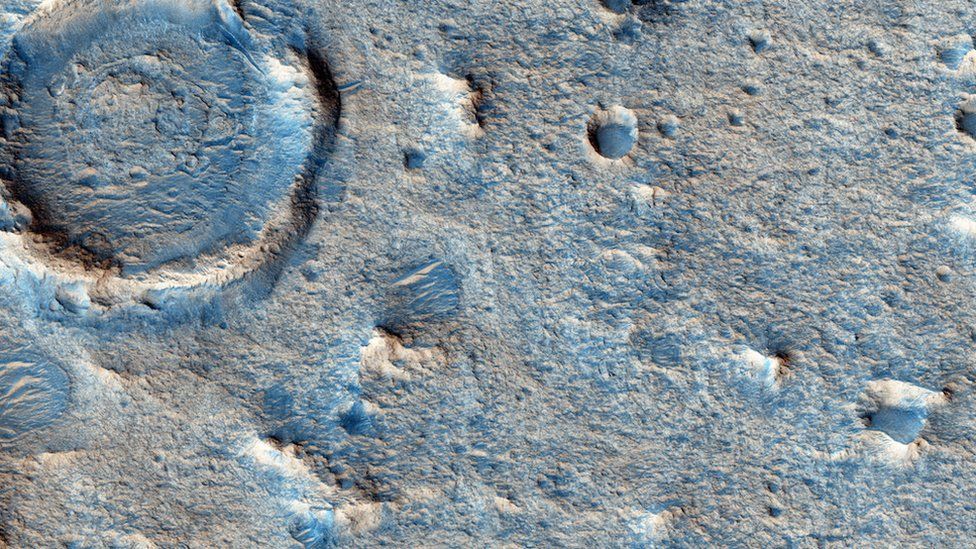

Much larger Russian components than the infrared spectrometer also need to be substituted with European-sourced elements, not least the rocket mechanism that will land Rosalind Franklin softly at a near-equatorial site on Mars known as Oxia Planum.

The late inclusion of Enfys does have the benefit that its performance requirements can be revisited.

An example is the range of infrared wavelengths in which it will be working.

Previously, there was going to be a gap in sensitivity between what Pancam could detect and what the old Russian spectrometer could see.

Enfys will be set up so that there is a slight overlap.

“We’ll now have spectral continuity from Pancam into the infrared, which is light we can’t see with our own eyes,” said Enfys team member Dr Claire Cousins from the University of St Andrews in Scotland.

“This mission will be very focused on looking for clay minerals, which have the greatest likelihood of preserving organic matter. And these minerals have very specific absorption bands in the infrared that Enfys will be able to see but that Pancam won’t.”

Aberystwyth University will be assisted on the new build by the Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London, STFC RAL Space in Harwell, Oxfordshire, and Qioptiq Ltd in St Asaph, Denbighshire.

The £10.7m being spent on Enfys brings the total UK investment in the Rosalind Franklin rover to £377m. With other members of Esa and help from the US space agency (Nasa), the total cost of the robot project will be well in excess of £1bn.

Dr Paul Bate, chief executive of the UK Space Agency, said: “The UK-built Rosalind Franklin rover is a truly world-leading piece of technology at the frontier of space exploration. It is fantastic that experts from the UK can also provide a key instrument for this mission, using UK Space Agency funding.

“As well as boosting world-class UK space technology to further our understanding of Mars and its potential to host life, this extra funding will strengthen collaboration across the fast-growing UK space sector and economy.”