Ukraine can now use Western arms to strike inside Russia

Denys, a serviceman in Kyiv on leave from Ukraine’s eastern front, is indignant about how long it takes for each round of Western arms supplies to reach the country.

“There’s always a ‘no’ first: No tanks. No missiles. No fighter jets,” he told Al Jazeera, referring to multiple times that Western allies have either refused to provide certain types of weapons to Ukraine or have strictly regulated their use. Denys withheld his last name and the location of his military unit in accordance with wartime regulations.

“And each ‘no’ costs lives. Not just ours. We’re big boys, we’ve seen life a bit, but those of children, the little children burned alive or blown to pieces …” the 27-year-old said, close to yelling, as he stood between a blossoming linden tree and an ice-cream kiosk in central Kyiv. “And then there’s a ‘maybe, maybe,’ and it goes on for months, and then there’s a ‘yes,’ but it’s always too late.”

Eventually, Western nations did agree to supply tanks, missiles and fighter jets – but after agonisingly long deliberations that cost lives, he said.

The latest “yes” from the United States and nearly a dozen Western nations that follows Russia’s recent advance and the relentless bombing of Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, grants their permission to use the advanced weaponry they have supplied – or will supply soon – to strike inside Russia.

Washington and its allies have been afraid of antagonising Russia, whose President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly suggested that the use of nuclear weapons is on the table in the event that Ukraine or the West cross yet another “red line” such as the shelling of Crimea and Putin’s pet project, a bridge that links it to mainland Russia.

But Ukraine has already crossed many military and political Rubicons, including the expulsion of Russian troops from occupied areas and drone strikes on airfields, military bases, ports and oil depots deep in Russia. These acts have left Moscow fuming, but not enough to use nuclear weapons.

The latest Western “yes”, which came on Thursday and followed months of pleas from Kyiv, is more of a “yes, but”.

The White House said that Kyiv can start using US-supplied weapons for “limited strikes” within Russia – but only in areas adjacent to the northeastern Kharkiv region that sits along the Russian border.

Russian forces seized the region and its eponymous administrative capital in early 2022, but were pushed out months later following a manoeuvre masterminded by Ukraine’s current top general, Oleksandr Syrskii.

Moscow resumed its attempts to take over Kharkiv in early May, seizing several border villages next to the western Russian region of Belgorod. The existing artillery in the area allowed troops to advance on Ukrainian targets and then retreat back to Russian soil, where they knew they would be safe from Ukrainian defence forces.

The White House’s latest “yes, but” applies to air defence systems, artillery and guided rockets. There is still a ban on long-range missile strikes.

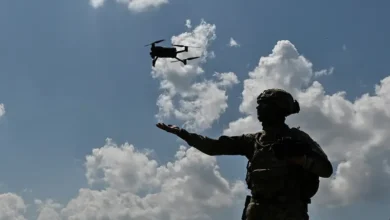

Other Western weapons that can now be used to hit Russia include 24 Dutch F-16 fighter jets armed with long-range missiles, and Soviet-era jets supplied by Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia and Northern Macedonia – countries that also granted their permissions in recent days.

Ukrainian pilots will soon complete their months-long training to fly F-16s and may fly their first sorties within weeks. Until now, their missions would have had to be limited to Ukrainian airspace. Not anymore.

The jets – along with a handful of Ukraine’s own Soviet aircraft – will be free to launch French-made air-launched cruise missiles known as Systeme de Croisiere Autonome a Longue Portee (SCALP) EG missiles.

The United Kingdom has not yet given permission to use the SCALP’s nearly identical twin missile, Storm Shadow – but has previously authorised the use of its attack drones on Russian soil. Turkey has also allowed Ukraine to use its Bayraktar drones there.

The US, the UK, Germany and Norway have already supplied Ukraine with ground-based launchers for HIMARS and ATACMS missiles that initially proved effective in strikes on annexed Crimea and occupied Ukrainian regions.

But Russia has in recent weeks begun using advanced electronic jamming systems to render these satellite-guided missiles – along with GPS-guided Excalibur artillery shells – ineffective.

“They [Russians] advanced a lot,” said Lieutenant General Ihor Romanenko, the former deputy head of Ukraine’s General Staff of Armed Forces. “We’re taking it seriously. We have to create our own means of suppressing their electronic jamming and create our own jamming systems,” he told Al Jazeera.

But the Western permission will hardly be a game-changer.