The 3,000m-high border that’s melting away

Changes that begin in the ice at the tops of high mountain ranges are cascading down to lower altitudes. As the world warms, they are changing borders, livelihoods and the shapes of mountains along the way.

It is a sunny day in autumn, and I am walking up a rocky slope next to a glacier at around 3,000m (9,800ft) above sea level, on the border between Austria and Italy. Next to me is Paul Grüner, the owner of a mountain refuge on the Italian side, which overlooks the glacier. Two brown ibexes – a type of wild mountain goat – graze peacefully by a turquoise glacial lake, their long, curved horns peeking out between the rocks. At our feet, a southern slope leads down into Italy, and on the other side, a northern slope faces Austria. Nearby, a weather-beaten wooden signpost with an arrow reads “Grenze / Confine” – meaning “border”, in German and Italian, both of which are spoken in this multilingual area.

Grüner, who has been running the refuge since the 1980s, has invited me up here to show me how much the glacier, called Hochjochferner has dwindled due to global warming. One startling consequence: its meltwater, which used to flow into both Austria to the north and Italy to the south, now just flows into one country, Austria. That’s because the southern part of the glacier has retreated much more dramatically than the northern part, and is now gone, those familiar with the glacier say. It’s just one example of how profoundly climate change is reshaping the mountains – with far-reaching consequences for everything from border relations, to hazards such as rockfall, to Europe’s water supply.

“When I was a child, the glacier covered this entire ridge, and the meltwater on that side flowed down to Italy,” says Grüner, who grew up in the area, gesturing at the south-facing slope. That slope is now rocky and bare. “And now it flows down here, and into Austria,” he adds, and gestures at the slope below our feet, which points down towards that country.

Adapting a border

“Here in the Alps, one of the most striking consequences of glacier loss is the difference in meltwater. For example, when the water suddenly goes down the ‘wrong’ side of a mountain, and is then missing on the other side,” says Andrea Fischer, a glaciologist and vice-director of the Institute of Interdisciplinary Mountain Research at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. That’s what happened with the Hochjochferner, she says. “Because of the glacier’s retreat, the meltwater no longer flows down to the south, and instead, flows to the north, to Austria.”

Sophie Hardach

Sophie HardachWhen a retreating glacier sits at a national boundary, the consequences can even redraw the political map.

“Since 2022, we’ve had extreme glacier loss, much more than in previous extreme years,” says Fischer. “The loss is especially big at the high altitudes, and that’s where the borders tend to be.”

Austria and Italy’s border was drawn in 1919, after the countries fought a high-altitude war. Mountain ridges define parts of the border, while other parts are defined by straight lines between peaks, Fischer says. So if a peak collapses, or icy ridges melt, “it can affect the border, and cause it to shift”, she says.

The two countries acknowledged the role of melting glaciers in their 2006 border treaty, which states that their border “follows the gradual, natural changes” of ridges, including those caused by changing glaciers. If a glacier disappears altogether, the border is then defined as running along the exposed rocky watershed. Because both countries are in the European Union, the border is in any case open. Switzerland and Italy are also in the process of adjusting their border due to shrinking glaciers.

The impact of shrinking glaciers can be felt as far as the Netherlands

But there’s also a much bigger cross-border consequence, experts say. The Alps are known as Europe’s water tower, as their runoff and meltwater feeds into big rivers, such as the Rhine, that pass through several countries.

Glacier meltwater is an important part of that supply because it replenishes the rivers at the height of summer, during hot, rainless periods, says Matthias Huss, a glaciologist at ETH Zurich who monitors glaciers in Switzerland. Missing meltwater from Alpine glaciers can therefore cause problems as far as the Netherlands, he says.

“Glaciers are retreating at an ever-faster rate,” warns Huss, who has had a close-up view of that change.

“When you monitor a glacier, you experience these changes very vividly,” he says. “You walk along the same trail every year, to the same place. And then one day, after decades of measurements, there comes the moment when you realise, it’s over now. The ice is so small, you can’t measure it anymore, or maybe the area has become inaccessible, due to rockfall,” as the ice no longer glues the rocks together.

At those moments, he packs up his instruments and leaves, walking back down one last time with the dismantled equipment on his back. “And of course we expected that loss, but when it happens, it can feel emotional,” says Huss.

‘Wildly romantic’ sled rides

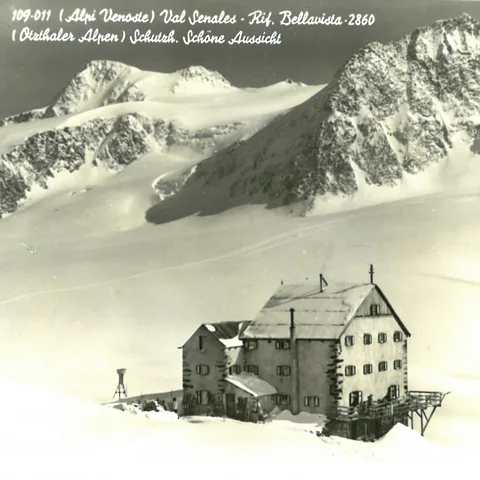

In the cosy, wood-panelled dining room of his sturdy refuge on the Italian side of the border, Grüner shows me a time series of the shrinking Hochjochferner that runs along the wall. He co-authored a book about the refuge – called Schöne Aussicht – Bella Vista (“Beautiful View”, in German and Italian) – for its 125-year anniversary, documenting its eventful history. In the 19th Century, when the glacier was vast, tourists even crossed it on a sled drawn by horses or mules in the summer.

“In July, August and September, one can go on a sled ride in this wildly romantic area, 2,800m (9,200ft) above the sea,” noted an astonished observer in 1867, Grüner and his co-authors write.

At the time, there was no national border along the glacier since South Tyrol belonged to the county of Tyrol (also spelled Tirol) back then, and was part of the Habsburg Empire. After World War One, South Tyrol became part of Italy, and the border was drawn. (South Tyrol is still part of Italy.)

Paul Grüner

Paul GrünerThese days, the high mountains are seeing more visitors than ever, and tourism here is booming. But Alpine mountaineering clubs have warned that many refuges are struggling with water shortages as their local supply dries up, due to the glaciers’ retreat, and less snow. Some are replacing flushing toilets with dry toilets, scrapping showers, and asking guests to buy bottled water to brush their teeth.

Grüner has not been affected, he says, as he has an alternative water supply: his own deep mountain spring, which he found in the 1990s. But he knows of other refuges that “don’t have any water left, and they have to pump it up from further down,” he says.

Some traditions remain unbroken: farmers from the Italian side of the Hochjochferner take thousands of sheep over to the Austrian side every year, as they have done for generations, using ancient herding rights. Only these days, instead of walking across the glacier, they walk across rocks.

“The Hochjochferner is vanishing before our eyes. In a few years’ time, it will be gone,” says Ulrich Strasser, a professor at the University of Innsbruck in Austria who specialises in modelling water and snow conditions in the Alps, and is part of a team observing this glacier and others.

Carleen Tijm-Reijmer, an associate professor in polar meteorology at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, has been visiting the Hochjochferner for interdisciplinary research since 2003. She has also co-organised a long-running summer school in the area, for glaciology students. “My impression of the retreat is a sad one, and perhaps also a feeling of being a bit privileged that I have seen the glaciers in the Alps when they were larger and still there,” she says.

Strasser says this emotional impact deserves more attention.

“We humans are good at finding technical solutions that replace natural features,” he says. Strasser suggests that water could for example be stored in reservoirs, to make up for missing glaciers. “But a glacier is of course much more beautiful than a giant reservoir. And that’s what we’re not discussing enough, this question of natural beauty. If we don’t protect our remaining natural landscapes, then future generations won’t even know what they’re missing. They will just think that’s what the mountains look like: a landscape of bare rocks.”

Walking around Grüner’s refuge, my hiking pole scratching against the bare scree where horse-drawn sleds once glided across smooth ice, I get a close-up view of this transformation – as Huss puts it, a “landscape changing from white to grey”.

Sophie Hardach

Sophie HardachIt may not be too late to prevent total loss: while small glaciers like the Hochjochferner are vanishing, scientists suggest climate action could still save parts of the biggest glaciers. And there is one thing that helps enormously when dealing with the problem, the scientists say: friendly cross-border relations.

From barbed wire to an open border

When Grüner took over the refuge in the 1980s, one of his first tasks was to clear away rolls of barbed wire left by the Italian military, after an Italian crackdown on German-speaking, South Tyrolean separatists. Those tensions were resolved, thanks to autonomy agreements.

In fact, Grüner and his team now cross the open border every day, to make beds: his refuge is on the Italian side, but he also runs a micro-hotel over on the Austrian side, in a former Austrian toll house that sleeps two people. “The border doesn’t affect me at all,” he says.

Fischer sees this openness as helpful in many ways: “Being under the European umbrella is really good for solving these sorts of issues, because no matter how much the border shifts, it’s definitely still in Europe”.

In areas where diplomatic relations are tense or non-existent, however, glacier loss can cause cross-border strife.

Cross-border catastrophes

The Hindu Kush Himalaya mountain range, for example, supplies water to people in eight different countries including China, India, Pakistan and Nepal – several of which have hostile relations.

The actual national borders in the area may not be that affected by glacial melting, says Miriam Jackson. She is the Eurasia director of the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, a network of policy experts and scientists specialising in the cryosphere (the Earth’s frozen areas). The mountain borders in the Hindu Kush Himalaya tend to cross very high glaciers, which are not yet melting, she says. The ones already disappearing are lower. However, the retreat of these lower glaciers can still cause trouble across borders, she says.

“The water doesn’t recognise national borders – rivers are often transboundary,” Jackson says. “This is true in Europe, and it’s also true in the Hindu Kush Himalaya.” Even people who live a long way away, who have probably never seen a glacier, could be very dependent on the meltwater from that glacier, she says. A glacier vanishing in one country could leave another country’s farmers dry.

Paul Grüner

Paul GrünerAnother risk is climate-related disasters. In 2016, a glacial lake, which had formed as the result of melting ice, burst in China and caused catastrophic downstream damage in Nepal.

“This [issue of glacial lakes] is a huge problem,” Jackson says. As a person living in another country downstream, “you might not even know the lake is there, and if it’s in another country, you can’t do anything about it” – such as monitoring it, or installing early-warning systems, she says.

There could be more water-related disasters in store for the Alps too, says Fischer, which might in turn affect Europe’s changing borders. “Laser scanning has revealed that the mountains in general are much less stable than we thought, even in areas where they look the same,” she explains, due to melting permafrost inside the mountains. “So here in the high mountains, having a border that’s 100% fixed, is not going to be possible in the long term.”

The mountains are a sanctuary – Paul Grüner

Over home-made apple strudel at his refuge, Grüner reflects on our relationship with the mountains. These days, we can get up them much faster than before, thanks to modern equipment, he says. “It feels like the mountains have become smaller and closer, since I was a child,” he says.

In the past, refuges like his own provided a necessary, practical function, he explains, because back then “you couldn’t go straight from the valley to the summit, you had to stay somewhere overnight”. That practical function is gone, he says, since these days, you could go straight to the summit, and skip the refuge. And yet, Alpine mountain refuges are more popular than ever.

“We don’t need refuges for practical reasons anymore. But I think today we have a need for refuges in another, metaphorical sense – as protective spaces, where humans can get away from their daily worries,” says Grüner. “If you look at why people go into the mountains these days, it’s to get in touch with themselves, and to feel good. Down in the valley, life is so busy. Up here, it’s still calmer. The mountains are a sanctuary.”