Osiris-Rex: Asteroid Bennu ‘is a journey back to our origins’

Nasa’s Osiris-Rex capsule will come screaming into Earth’s atmosphere on Sunday at more than 15 times the speed of a rifle bullet.

It will make a fireball in the sky as it does so, but a heat shield and parachutes will slow the descent and bring it into a gentle touchdown in Utah’s West Desert.

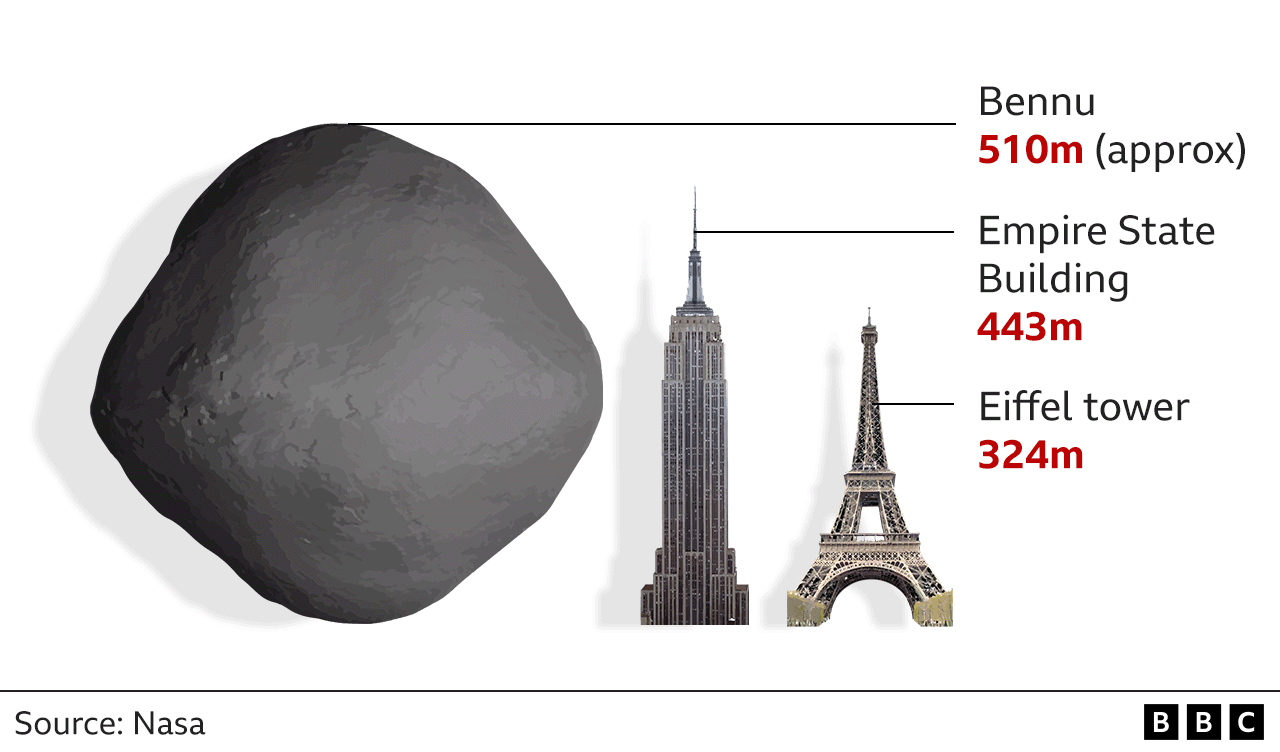

The capsule carries a precious cargo – a handful of dust grabbed from asteroid Bennu, a mountain-sized space rock that promises to inform the most profound of questions: Where do we come from?

“When we get the 250g (9oz) of asteroid Bennu back on Earth, we’ll be looking at material that existed before our planet, maybe even some grains that existed before our Solar System,” says Prof Dante Lauretta, the principal investigator on the mission.

“We’re trying to piece together our beginnings. How did the Earth form and why is it a habitable world? Where did the oceans get their water; where did the air in our atmosphere come from; and most importantly, what is the source of the organic molecules that make up all life on Earth?”

The prevailing thinking is that many of the key components were actually delivered to our planet early in its history in a rain of impacting asteroids, many of them perhaps just like Bennu.

Engineers have commanded the final adjustments to the Osiris-Rex spacecraft’s trajectory. All that remains is to make the “go, no-go” decision to release the capsule to fall to Earth this weekend.

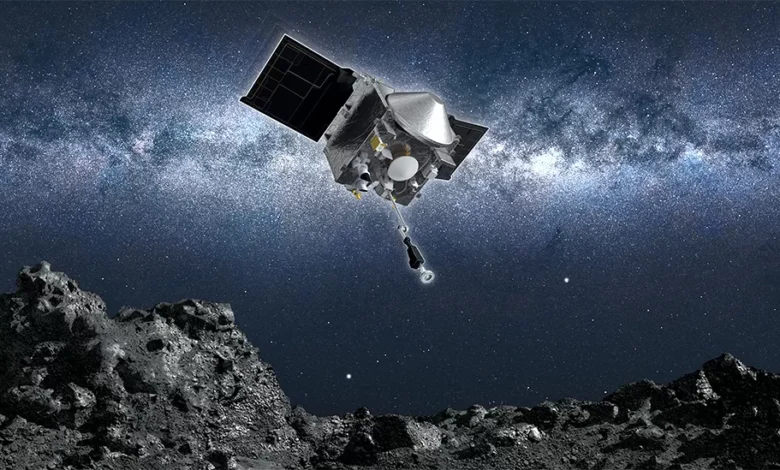

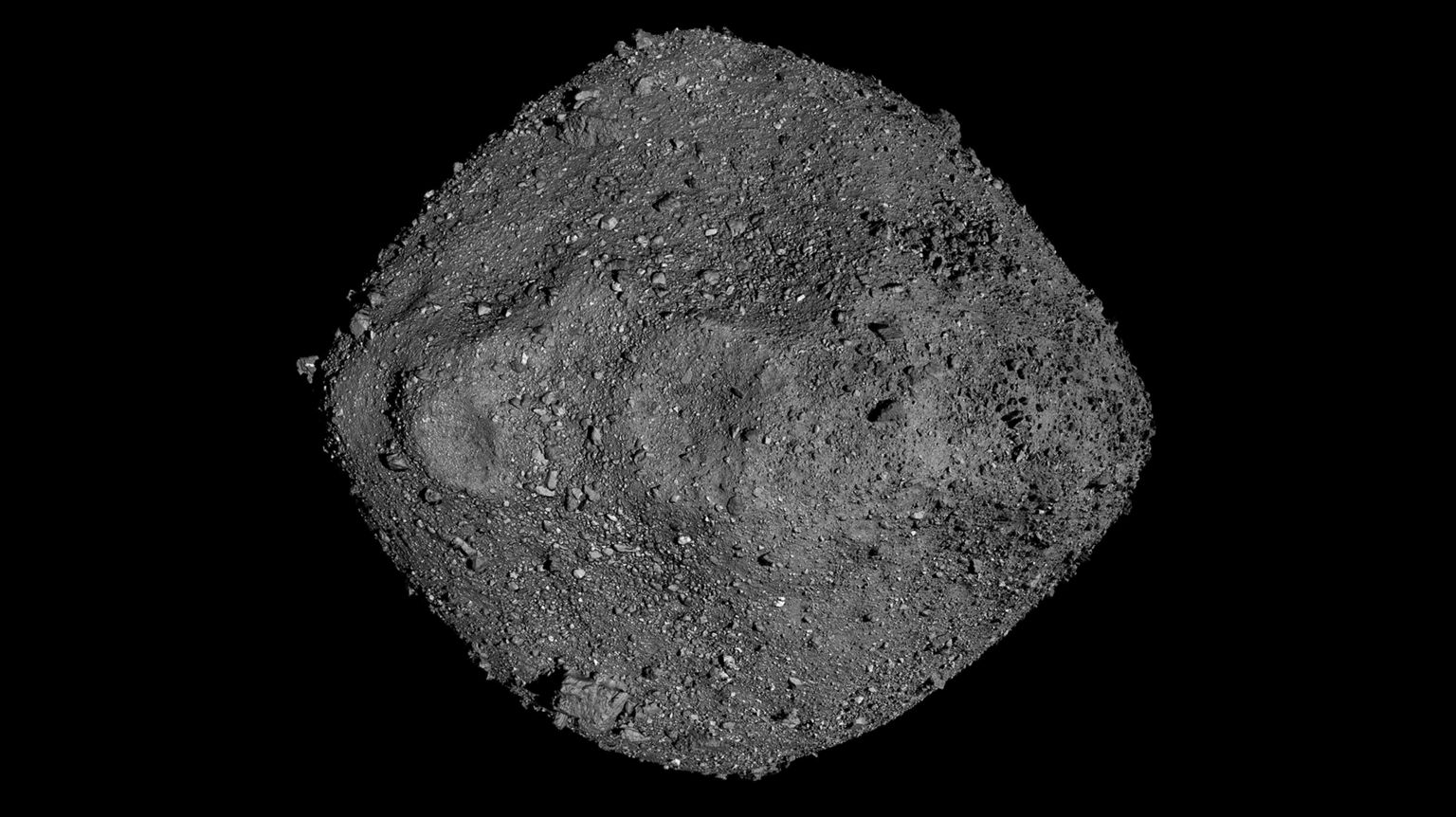

The quest to acquire fragments of Bennu began in 2016, when Nasa launched the Osiris-Rex probe towards the 500m (1,640ft) wide object. It took two years to reach the body and a further two years of mapping before the mission team could confidently identify a location on the space rock’s surface to scoop up a “soil” sample.

Key to that choice was the British rock legend and astrophysicist Dr Sir Brian May. The Queen guitarist is an expert in stereo imaging.

He has the ability to align two pictures of a subject taken from slightly different angles to give a sense of perspective – making a 3D view of a scene. He and collaborator Claudia Manzoni did this for the shortlist of possible sample sites on Bennu. They established the safest places to approach.

“I always say you need art as well as science,” Sir Brian said. “You need to feel the terrain to know if the spaceship is likely to fall over or if it will hit this ‘rock of doom’ that was right on the edge of the eventual chosen site, called Nightingale. If that had happened it would have been disastrous.”

The moment of sample capture, on 20 October 2020, was astonishing.

Osiris-Rex lowered itself down to the asteroid – holding its grabbing mechanism on the end of a 3m-long (10ft) boom.

The idea was to slap the surface and, at the same time, give out a blast of nitrogen gas to kick up gravel and dust. What happened next was something of a shock.

When the mechanism made contact, the surface parted like a fluid. By the time the gas fired, the disc was 10cm (4in) down. The nitrogen pressure blasted a crater 8m (26ft) in diameter. Material flew in all directions, but crucially also into the collection chamber.

And so now here we are. Osiris-Rex is just hours away from delivering the Bennu sample at the end of what has been a seven-year, seven-billion-kilometre round trip.

Once the capsule is safely on the ground, it will be whisked off to the Johnson Space Center in Texas, where a dedicated cleanroom has been built to analyse the samples.

Dr Ashley King from London’s Natural History Museum (NHM) will be one of the very first scientists to get his gloves on the material. He is part of the “quick look” team that will do the initial analysis.

“Bringing back samples from an asteroid – we don’t do that very often. So you want to do those first measurements, and you want to do them really well,” he says. “It’s incredibly exciting.”

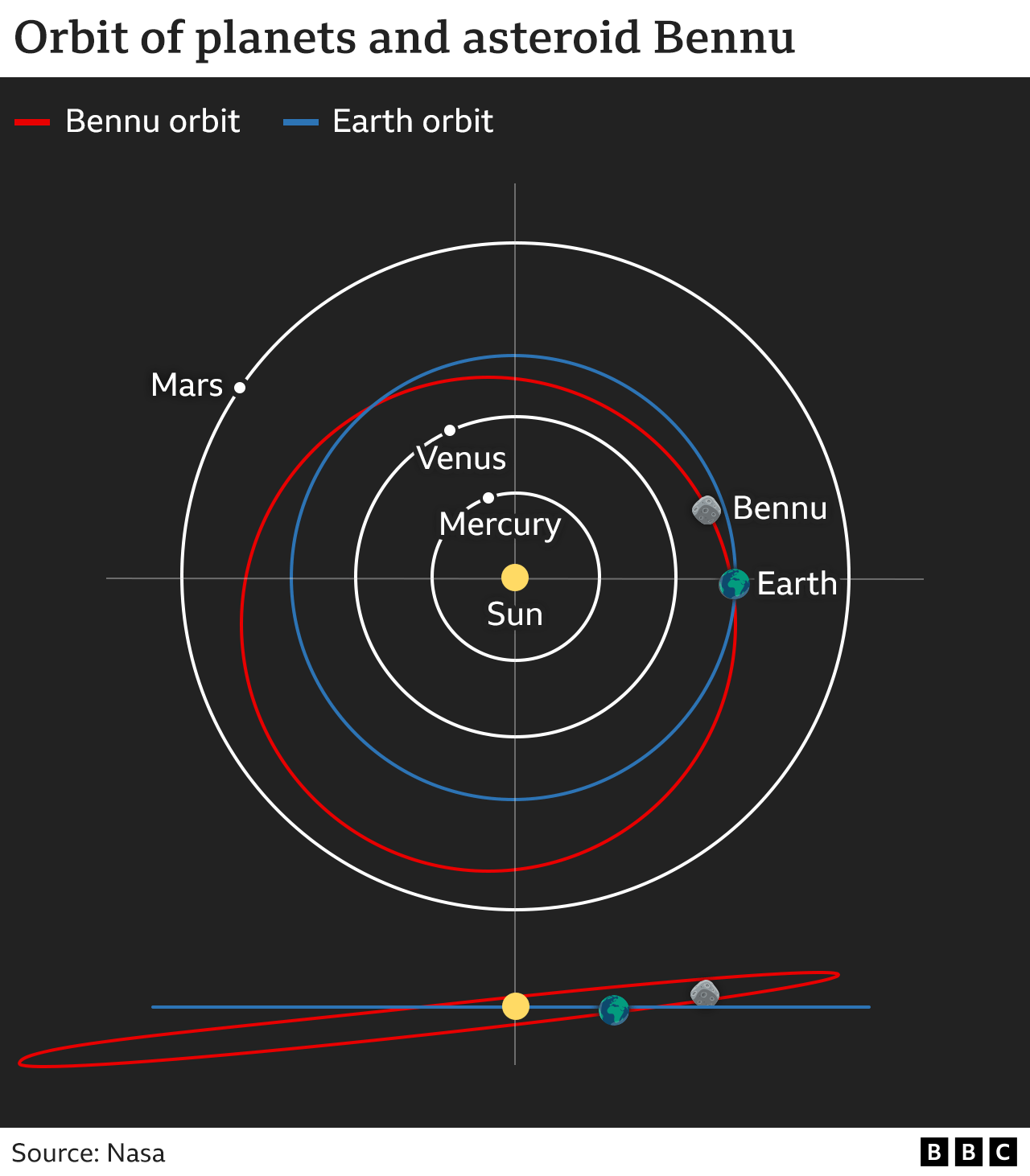

Nasa regards Bennu as the most dangerous rock in the Solar System. Its path through space gives it the highest probability of impacting Earth of any known asteroid. But don’t panic, the chances are very slim – akin to tossing a coin and getting 11 heads in a row. And any impact isn’t likely until late next century.

Bennu probably contains a lot of water – as much as 10% by weight – bound up in its minerals. Scientists will be looking to see if the ratio of different types of hydrogen atoms in this water is similar to that in Earth’s oceans.

If, as some experts believe, the early Earth was so hot that it lost much of its water, then finding an H₂O match with Bennu would bolster the idea that later bombardment from asteroids was important in providing volume for our oceans.

Bennu probably also contains about 5-10% by weight of carbon. This is where a lot of the interest lies. As we know, life on our planet is based on organic chemistry. As well as water, did complex molecules have to be delivered from space to kickstart biology on the young Earth?

“One of the very first analyses to be done on the sample will include an inventory of all of the carbon-based molecules that it contains,” says the NHM’s Prof Sara Russell.

“We know from looking at meteorites that asteroids are likely to contain a zoo of different organic molecules. But in meteorites, they’re often very contaminated, and so this sample return gives us a chance to really find out what the pristine organic components of Bennu are.”

Prof Lauretta adds: “We’ve actually never looked for the amino acids that are used in proteins in meteorites because of this contamination issue. So we think we’re really going to advance our understanding of what we call the exogenous delivery hypothesis, the idea that these asteroids were the source of the building blocks of life.”