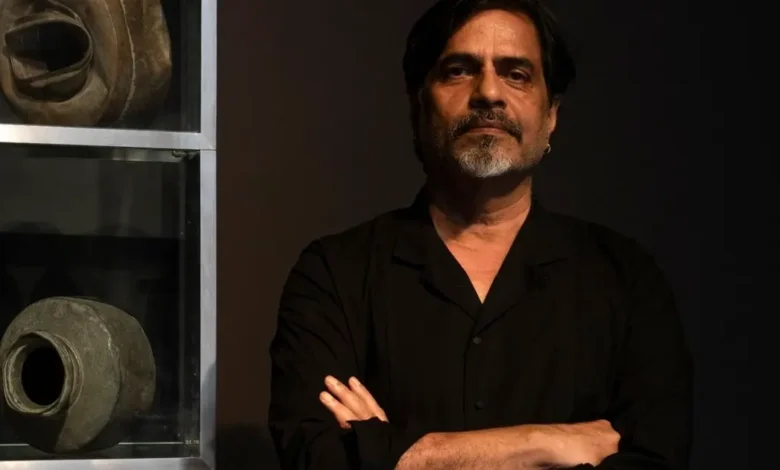

‘Only Life, Myriad Places’: Sudarshan Shetty and sensing the world in multiple ways

The high point of Sudarshan Shetty’s solo exhibition at the Ishara Art Foundation in Dubai titled ‘Only Life, Myriad Places’ is the artist’s latest film, ‘One Life Many,’ which had its global premiere at the venue.

The exhibition also marks the first survey of Shetty’s moving image works, enabling the viewer to zero in on the artist’s rarely-seen videos, multimedia installations, and sculptures.

Sabih Ahmed, Curator of the show and Associate Director of Ishara Art Foundation, has thoughtfully presented the works in a layered format, and ‘One Life Many’ is ideally positioned amid the other works, enabling the viewer to progressively gain more insights into the inner workings of the artist’s mind as well as his craft. “We decided to bring together his video works because he has carried forward the tradition of storytelling that is very close to his thinking process.”

‘Only Life, Myriad Places’ reflects on the nation’s rich music, literature, and storytelling traditions echoing through the ages and permeating through the eyes and craft of Mumbai-based Shetty, one of India’s leading practitioners of contemporary art.

Trained as a painter at the Sir J.J. School of Art in Mumbai, Shetty is critically acclaimed as a conceptual artist known for his sculptures and multimedia installations. as his primary mediums.

Shetty comes from a family with a tradition of story-telling and growing up in Mumbai, the home of Indian cinema, he has also absorbed the ethos of film culture. His art is thus a fusion of Indian and Western traditions that explores the “inner and outer realities of everyday life.”

‘Poetics of listening’

In ‘Only Life, Myriad Places’ curator Sabih Ahmed unveils eight significant works – objects, images, texts, and videos, that prioritize the act of hearing over seeing, harking back to the musical and literary traditions of South Asia, upholding the ‘poetics of listening.’

“What we have tried to do curatorially is not to use ‘black box settings’ but to design the show as a labyrinth of the mind, where you can’t tell the difference between fact and fiction, and what is dream and what is reality. That is the space that Sudarshan wants to take you into when he makes these films.”

Sabih Ahmed also points to the [curatorial decision to use the] recurrent motif of the vessel or pot – a subtle reference to the recurring tales of human migration at the mundane and the transmigration of souls at a higher plane.

“It is one of the densest shows we have ever curated at Ishara – presenting a whole mise en scène of objects, sounds, and soundscapes, and an ambient environment. Stories of many lives, even of medieval times, retold through objects.”

Critics have noted “a rigorous grammar of materials” when commenting about Shetty’s work. But as the artist himself has averred, the seed comes from outside of the material.

‘Simulacrum of a virtual world’

At Ishara, Sabih Ahmed has chosen an untitled sculptural installation by Shetty comprising six pairs of vessels displayed inside a vertical glass vitrine to introduce the exhibition. Dented metallic pots rest on their side with mirror replicas sculpted in wood. The juxtaposition provides “an uncanny resemblance to percussive instruments” or represents “an abstract composition of progressive scales, and a duet of bodies resting silently together.”

As the curator notes, this mirror imaging is essential to Shetty’s work. “The mirror image is like a dream, the simulacrum of a virtual world.”

In the context of the Indian sub-continent, the vessel or pot historically harks back tales of migration. In Indian philosophical tradition, the clay pot represents life, death, and the transmigration of the soul.

In the exhibition, Sabih Ahmed also makes a curatorial choice to use the representation of the pot or vessel as a recurrent motif.

On the other side of the entrance wall, a single channel video titled ‘Waiting for others to arrive,’ staged in an abandoned Neoclassical building in Mumbai, with the stringed instrument of ‘Sarangi’ playing a melancholy tune mixed with the bustle of every day sounds in the vicinity. There are three identical frames, and as the Sarangi player finishes playing, a teacup on a table in the room moves and ultimately falls on the ground and breaks. There is a juxtaposition of stillness and movement, the interior and the outdoors. The movement, appearance, disappearance, and musical pathos make it a profoundly memorable exploration of the “philosophical conundrums of life, death, and afterlife.”

A ‘sonic metaphor’

Next into the exhibition is a grouping of three artworks, including an untitled installation with prints, a single channel video titled ‘The Juggler,’ and a text.

‘The Juggler’ shows a man juggling three earthen pots in slow motion. The pot here takes on the meaning of a vessel for ‘prana,’ the life force that animates all living things. The action takes place in silence, leaving a blurry echo of the pots in motion, a ‘sonic metaphor’ the artist wishes us to recall as it were.

The earthen pot reappears in an untitled installation, this time comprising three photographs of the artist throwing a pot of water over his shoulder in a funerary ritual captured in distinct moments against the colonial setting of the ‘Gateway of India’ and the presence of the sea.

An actual clay pot accompanying the photographs is on display, with its fragments pieced back together as a ‘shadow reassembled,’ and the cracks still visible on its surface. The afterlife of the pot is portrayed as having lost its physical integrity but retaining its past.

The third work in the room is an untitled text (vinyl text on wood) by Shetty presented on a ledge, once again conjuring the image of a cracked earthen pot inside a domestic space of a kitchen. The text evokes a three-dimensional image and the distinct presence of the feminine in that space.

These three works are the artist’s philosophical contemplation of the nature of life and death and what finally lives on.

Sabih Ahmed places Shetty’s most recent and ambitious film ‘One Life Many’ as the fulcrum of the exhibition. Drawing from a medieval Indian myth of a sage who transforms into another being and back, the film is a fascinating insight into the multitude of selves inside us.

The film also explores the contours of daily life as we see the world shake off the torpor following the pandemic, and we follow along with the protagonist across “empty streets, a busy marketplace, bus terminals, and a vast body of water set against the horizon.”

‘A multitude of selves’

Folklore, dreams, recollections and the diversity of lives and regeneration provide the underpinnings to the thematic framework of ‘One Life Many,’ which raises “the age-old question about how can there be one true self we identify with, when we also carry a multitude of selves inside of us.”

The following work, a two-channel video titled ‘A Song A Story’ is also a popular medieval Indian folktale that has been passed on in many forms across the country.

Two hand-carved wooden installations designed by Shetty – namely a home and a pavilion – serve as the dramatis personae of the work. The narrative unfolds around a woman who has held onto her song and story for a long time. But ultimately, they escape, taking on the form of an umbrella and a pair of man’s shoes stationed outside her door, resulting in a misunderstanding when her husband returns.

The story – told and retold on multiple screens of the two channels and the television inside the video – unfolds over mistrust and closure. In this work, what remains unconscious or neglected takes a life of its own, traversing its characters’ domestic and public domains and seeping into the world outside.

As usual, the curator has something special on the mezzanine floor: ‘Age of Love’ is the final work in the exhibition. The multimedia installation derives its title from a musical composition featured in the video.

Shetty was invited to make a film on the theme of love. Carefully selected from the vast tradition of Hindustani classical music, six intergenerational singers string together elaborate renditions in praise of love – the fragile and ungraspable nature of which escapes reason. Notable in the work is that the word love is not mentioned even once. The singers appear and disappear in a domestic environment, at the center of which is a huge dining table with chairs; a chandelier looms large and finally collapses in the last frame.

‘Blending of myths, legends, and folktales’

After navigating ‘One Life, Myriad Places,’ the viewer will find the realms of the “sacred, the mystical, and the mundane” hovering above these works or emanating from them.

Reflecting on the exhibition, Sudarshan Shetty comments: “Like in the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East has a captivating tradition of poetry and storytelling deeply entrenched in its history. The interaction between these two distant lands has fostered a cross-pollination of stories, which has resulted in a blending of myths, legends, and folktales, creating a vibrant mosaic that resonates through both regions. Retelling is the lifeblood of oral traditions, ensuring a sense of community and recalling wisdom that has evolved through centuries. How else can we make sense of our present?”

As for Sabih Ahmed, “By prioritizing the act of hearing as opposed to seeing in one’s experience of art, ‘One Life, Myriad Places’ is a call to sense the world in multiple ways.”

The exhibition is open till December 9, 2023.