‘More than meets the eye’: The hidden meanings in a US masterpiece

The painting School of Beauty, School of Culture is among the exhibits in a major new London retrospective of the US artist Kerry James Marshall. But there is more to the salon scene than first meets the eye.

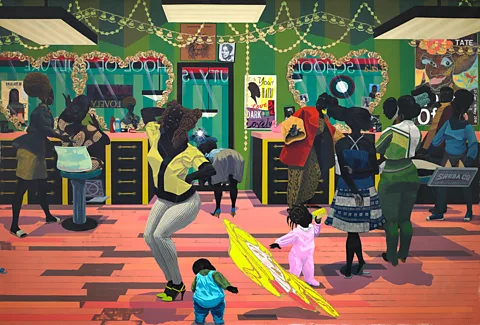

At nine feet tall and 13 feet wide, School of Beauty, School of Culture doesn’t just tower over its viewers; it invites them in. “If you want to make a painting that many people can look at together and that can compete with paintings in big museums, then it’s got to have scale,” explains art historian Mark Godfrey, curator of Kerry James Marshall: The Histories at the Royal Academy, London. “The painting has its own wall” in the exhibition, he tells the BBC, “and can be seen from a distance of about 60 metres away.”

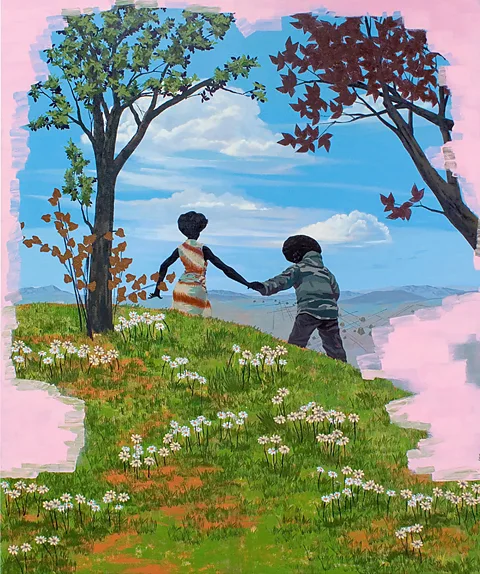

The US figurative painter is among the most acclaimed living artists in the world, and in 2018 set a new record when his Past Times sold at auction for $21.1 million – a groundbreaking amount for a work by a living African-American artist at the time. The Royal Academy show, which opens today, is the largest survey of his art ever shown in Europe. “Staggering, triumphant”, “ingenious” and “astonishing” are just some of the glowing epithets recently used in reviews of the exhibition. “Prepare to be bewitched,” says another. And nothing in it is more bewitching than School of Beauty, School of Culture.

Completed in 2012, the painting presents an everyday scene, yet like the other artworks displayed in The Histories, there is more to it than initially meets the eye. The scenario is layered with multiple coded references from history, culture and art history, from Disney to Holbein.

The lively scene in a bustling hair salon buzzes with activity. In one corner, a woman flails her arms as she chats with her hairdresser. In another, a group of men and women congregate. Slightly off-centre, a poised woman, dressed in a yellow-and-black shirt and striped trousers, stares directly at us. Her knees are bent, one arm leans on the back of her head, the other on her waist. She poses as two children play at her feet. It’s a magnificent scene, conveying all the hubbub of a local business that doubles as a community hub.

He will refer to Raphael and Holbein because he is a scholar of painting, and he’ll refer to Lauryn Hill because he’s a person in the world – Mark Godfrey

Like many great painters before him, Marshall transforms everyday life into remarkable works of art. But unlike most previous works known for their portrayals of contemporary scenes – from Édouard Manet’s scenes of Parisian cafés to Georges Seurat’s large-scale depiction of a Sunday afternoon in Paris – all of the figures in School of Beauty, School of Culture are black.

“I’m more interested in the specificity of beauty shops and barbershops for black subjects because that’s where I am and who I am,” the artist tells the BBC at an advance showing of the exhibition. “What is the place for? What does the place mean? What happens there? That’s largely what the picture is about.”

Around the corner from his studio in Chicago, where Marshall has lived for almost four decades, there is a beauty school “where they teach classes in cosmetology, manicuring, all of that stuff”, he notes, pointing out that such salons are both a part of ordinary life and a place of healing magic. “People go in and they come out transformed: they come out polished, they come out made up, they come out done.”

Despite its almost 26-year gap, School of Beauty, School of Culture is in direct conversation with an earlier work by Marshall, De Style (1993), which depicts a black barbershop. Named with reference to the Dutch art movement De Stijl, founded in 1917 by the painter Piet Mondrian, Marshall uses primary colours and precisely arranged salon furniture to reference the abstract paintings of that time. But most striking is the gravity-defying hairstyles of two of its figures, and the Christ-like hand gesture of the barber, signalling the importance of such institutions within the black community.

Marshall isn’t alone in recognising the significance of these spaces. Many black artists, film-makers and writers have explored them in their work, from the 2017 play Barber Shop Chronicles by the Nigerian writer Inua Ellams, which probes the setting in five African cities, to the British-Jamaican painter Hurvin Anderson’s consistent examination of the subject since 2006, when he first painted a barbershop in Birmingham, UK.

I’m always trying to make the densest, most compact, complicated pictures I can make – more is more – Kerry James Marshall

School of Beauty, School of Culture “is a painting I meant to do when I finished De Style”, explains Marshall, noting that other projects got in the way. “But I was always planning to do it in order to represent the entire scope of the way in which people go to places to make themselves into the best version of themselves.”

Art-history references

There is more to the painting than first meets the eye, however. Much like many pieces by the artist, School of Beauty, School of Culture is packed with layers of both art-historical and modern black references. “This is [part of] a pretty consistent pattern of adding density to the picture,” Marshall adds. “I’m always trying to make the densest, most compact, complicated pictures I can make. More is more.”

As Godfrey puts it: “He really respects the tradition of Western art. What he challenges is the fact that Western art museums haven’t, until recently, had large-scale paintings featuring black people.”

Most notably, in the foreground of the painting, a distorted, anamorphic depiction of Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty in yellow is scrutinised by an intrigued toddler in dungarees. This detail directly references Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors (1533), in which two friends stand among an array of artefacts, while a distorted skull is hidden at the bottom. “In that painting, Holbein was thinking about how their lives were haunted by death,” explains Godfrey. “Kerry uses that idea to think about how white standards of beauty might intrude upon the beauty salon.”

Marshall also scatters mirrors across School of Beauty, School of Culture, a nod to Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait(1434) and Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656), two works renowned for playing with reflection. In Van Eyck’s domestic scenes, a curved mirror offers viewers an expanded view of the room. Meanwhile, the placement of the mirror at the back of Velázquez’s painting reveals the reflection of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana. In Marshall’s piece, as the woman at the centre poses, supposedly for the viewer, the mirror behind reveals the flash of a photographer’s camera, as he raises his arms in front of their face to take the photo. “Those are all very deliberate and direct references,” Marshall says. “But in general, for the average person, without any of those references, this place looks familiar.”

Nods to contemporary black culture are just as prevalent in the painting. A signed poster of Lauryn Hill and another for the UK-born artist Chris Ofili’s 2010 Tate Britain show are depicted on the walls of the salon. At the time of the Tate exhibition, Ofili was widely considered the most famous black artist in British history, though Marshall first saw Ofili’s work in New York before seeing it in London. “They were the best paintings I’d ever seen because they were rich, complex, and layered,” he says, adding that he believes Ofili “operates at the highest level that paintings can be made”.

For Godfrey, Marshall’s diverse mix of references, from art history to black culture, is part of his genius: “He will refer to Raphael and Holbein because he is a scholar of painting and its history, and he’ll refer to Lauryn Hill because he’s a person in the world and he listens to great music.”

However, the most striking feature of School of Beauty, School of Culture, much like most of Marshall’s works in the retrospective, is the figures themselves. Every individual in the salon is painted in a deep shade of black, which Godfrey says further forces viewers to think about “the presence of black people within large-scale paintings. In the ’60s and ’70s, especially in the States, people were beginning to use the word black with a capital B to refer to themselves and their identity”, Godfrey explains. “At that point, Marshall decided to make figures that were also black, literally.”

That said, Marshall’s approach to painting black figures has kept evolving. In A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980), the figure’s blackness is depicted as one-dimensional, the only defining facial features being the whites of his eyes and his wide, toothy grin. But he has since added increasing visual richness to the jet-black skin. “You start with black and then work from there to build up the most complexity you can by making the colours richer and richer and more sophisticated,” he explains. “Over time, you end up not with a flat cypher, but with a figure that’s fully dimensional.”

Like the people in most of his paintings, the figures in School of Beauty, School of Culture are fictional. “I don’t take pictures [photographs],” he says, gesturing towards me. “I wouldn’t take your picture and then paint you black.” In his mind, the figures he depicts have always had the degree of blackness they have in the paintings. “These figures were born black,” he says. “They are fundamentally black figures. They are black to the core.”