How warming oceans are driving the climate juggernaut

It is hot. Very hot. And we are only a few weeks into summer.

Texas and part of the south-west of the US are enduring a searing heatwave. At one point, more than 120 million Americans were under some form of heat advisory, the US National Weather Service said. That is more than one in three of the total population.

In the UK, the June heat didn’t just break all-time records, it smashed them. It was 0.9C hotter than the previous record, set back in 1940. That is a huge margin.

There is a similar story of unprecedented hot weather in North Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

No surprise, then, that the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather forecasts said that globally, June was the hottest on record.

And the heat has not eased. The three hottest days ever recorded were in the past week, according to the EU climate and weather service, Copernicus.

The average world temperature hit 16.89C on Monday 3 July and topped 17C for the first time on 4 July, with an average global temperature of 17.04C.

Provisional figures suggest that was exceeded on 5 July when temperatures reached 17.05C.

These highs are in line with what climate models predicted, says Prof Richard Betts, climate scientist at the Met Office and University of Exeter.

“We should not be at all surprised with the high global temperatures,” he says. “This is all a stark reminder of what we’ve known for a long time, and we will see ever more extremes until we stop building up more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.”

When we think about how hot it is, we tend to think about the air temperature, because that’s what we experience in our daily lives.

But most of the heat stored near the surface of the Earth is not in the atmosphere, but in the oceans. And we’ve been seeing some record ocean temperatures this spring and summer.

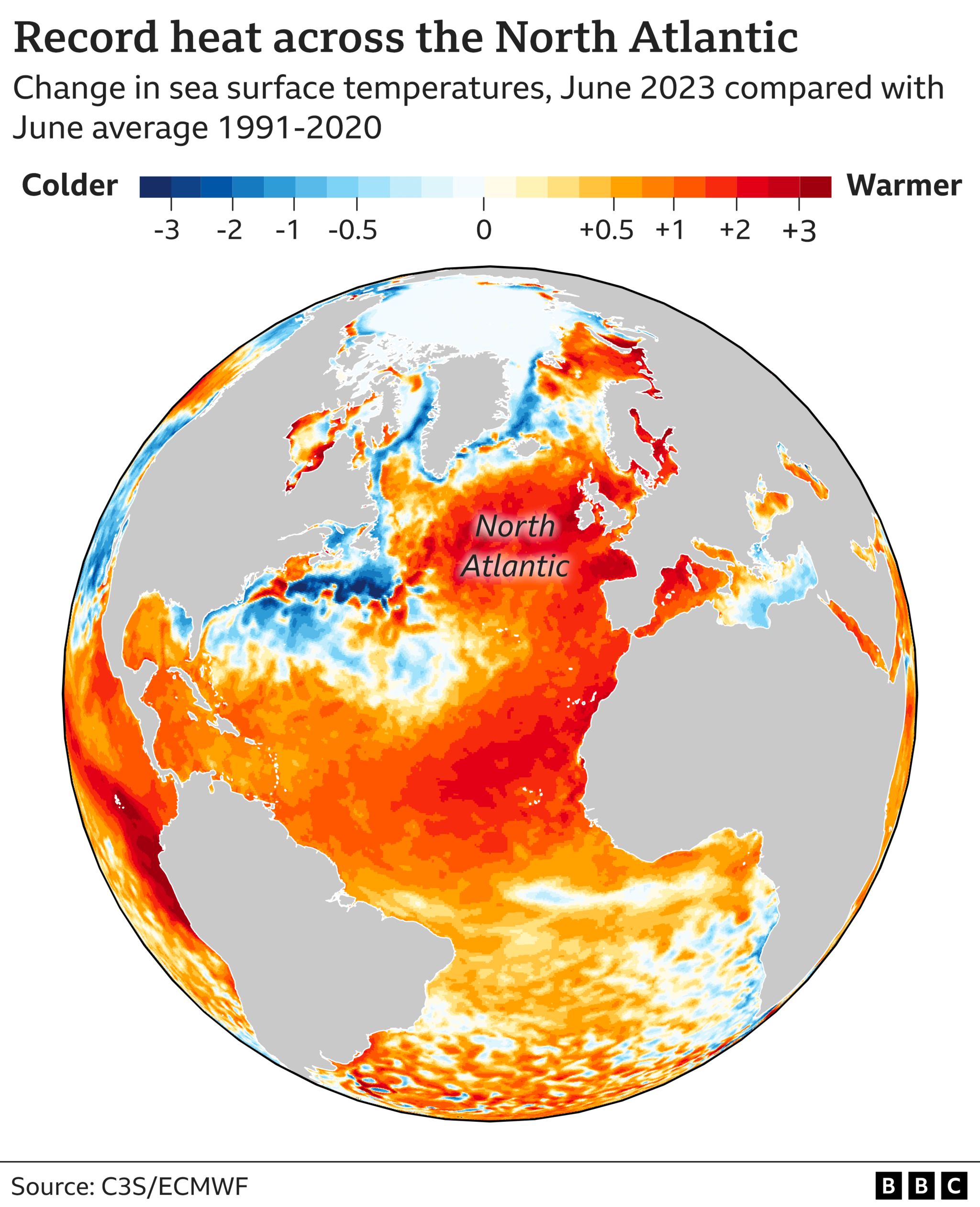

The North Atlantic, for example, is currently experiencing the highest surface water temperatures ever recorded.

That marine heatwave has been particularly pronounced around the coasts of the UK, where some areas have experienced temperatures as much as 5C above what you would normally expect for this time of year.

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has labelled it a Category 4 heatwave. The designation is rarely used outside of the tropics and denotes “extreme” heat.

“Such anomalous temperatures in this part of the North Atlantic are unheard of,” says Daniela Schmidt, a professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol.

At the same time, an El Niño is developing in the tropical Pacific.

El Niño is a recurring weather pattern caused when warm waters rise to the surface off the coast of South America and spread across the ocean.

With both the Atlantic and the Pacific experiencing heatwaves, it is perhaps not surprising that global sea surface temperatures for both April and May were the highest ever recorded in Met Office data that goes all the way back to 1850.

If the seas are warmer than usual, you can expect higher air temperatures too, says Tim Lenton, professor of climate change at Exeter University.

Most of the extra heat trapped by the build-up of greenhouse gases has gone into warming the surface ocean, he explains. That extra heat tends to get mixed downwards towards the deeper ocean, but movements in oceans currents – like El Niño – can bring it back to the surface.

“When that happens, a lot of that heat gets released into the atmosphere,” says Prof Lenton, “driving up air temperatures.”

It’s easy to think of this exceptionally hot weather as unusual, but the depressing truth is that climate change means it is now normal to experience record-breaking temperatures.

Greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase year on year. The rate of growth has slowed slightly, but energy-related CO2 emissions were still up almost 1% last year, according to the International Energy Agency, a global energy watchdog.

And the higher the global temperature, the higher the risk of heatwaves, says Friederike Otto, a climatologist at the Grantham Institute of Climate Change at Imperial College London.

“These heatwaves are not only more frequent, but also hotter and longer than they would have been without global warming,” she says.

Experts are already predicting that the developing El Niño is likely to make 2023 the world’s hottest year.

They fear it is likely to temporarily push the world past a key 1.5C warming milestone.

And that is just the start. Unless we make dramatic reductions to greenhouse gas emissions, temperatures will continue to rise.

The Met Office said this week that record June temperatures this year were made twice as likely because of man-made climate change.

These rising temperatures are already driving fundamental and almost certainly irreversible changes in ecosystems across the world.

The record June temperatures in the UK helped cause unprecedented deaths of fish in rivers and canals, for example.

We cannot know what impact the current marine heatwave will have on the UK, cautions Prof Schmidt of the University of Bristol, because we have never seen one this intense before.

“In other regions, around Australia, in the Mediterranean, entire ecosystems changed, kelp forests disappeared, and seabirds and whales starved,” she says.

The world is effectively in a race.

It is clear we are speeding towards an ever hotter and more chaotic climate future, but we do have the technologies and tools to cut our emissions.

The question now is whether we can do so rapidly enough to slow the climate juggernaut and keep the impacts of global warming within manageable boundaries.