How the humble chestnut traced the rise and fall of the Roman Empire

The chestnut trees of Europe tell a hidden story charting the fortunes of ancient Rome and the legacy it left in the continent’s forests.

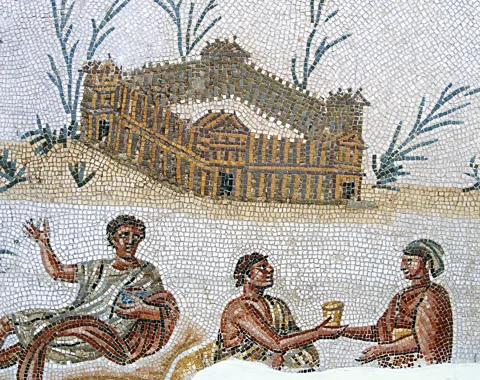

The ancient Romans left an indelible imprint on the world they enveloped into their empire. The straight, long-distance roads they built can still be followed beneath the asphalt of some modern highways. They spread aqueducts, sewers, public baths and the Latin language across much of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. But what’s perhaps less well known is the surprising way they transformed Europe’s forests.

According to researchers in Switzerland, the Romans had something of a penchant for sweet chestnut trees, spreading them across Europe. But it wasn’t so much the delicate, earthy chestnuts they craved – instead, it was the fast-regrowing timber they prized most, as raw material for their empire’s expansion. And this led to them exporting tree cultivation techniques such as coppicing too, which have helped the chestnut flourish across the continent.

“The Romans’ imprint on Europe was making it into a connected, economical space,” says Patrik Krebs, a geographer at the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL). “They built a single system of governance all over Europe, they improved the road system, the trade system, the military system, the connection between all the different people all over Europe.”

As a result of that connection, “specific skills in arboriculture [the cultivation of trees] were shared by all the different civilisations”, he says.

The arboreal legacy of the Romans can still be found today in many parts of Europe – more than 2.5 million hectares (6 million acres) of land are covered by sweet chestnut trees, an area equivalent in size to the island of Sardinia. The trees have become an important part of the landscape in many parts of the continent and remain part of the traditional cuisine of many countries including France and Portugal.

Krebs works at a branch of the WSL in Switzerland’s Ticino canton on the southern slope of the Alps, an area that is home to giant chestnut trees, where many specimens have girths greater than seven metres (23ft). By the time of the Middle Ages, sweet chestnuts were a staple food in the area. But it was the Romans who brought the trees there – before their arrival in Ticino, sweet chestnuts did not exist there, having been locally wiped out in the last ice age, which ended more than 10,000 years ago.

Using a wide range of evidence, including paleoecological pollen records and ancient Roman texts, Krebs’ research team analysed the distribution of both sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) and walnut (Juglans regia) trees in Europe before, during and after the Roman empire. Sweet chestnut and walnut trees are considered useful indicators of the human impact on a landscape, as they generally benefit from human management – such as pruning and supressing competing trees. Their fruits and timber are also highly desirable.

In countries such as Switzerland, France and parts of Germany, sweet chestnut pollen was near-absent from the wider pollen record – such as, for example, fossil pollen found in sediment and soil samples – before the Romans arrived, according to the study and previous research. But as the Roman Empire expanded, the presence of sweet chestnut pollen grew. Specifically, the percentage of sweet chestnut pollen relative to other pollen across Europe “shows a pattern of a sudden increase around year zero [0AD], when the power of the Roman empire was at its maximum” in Europe, Krebs says.

Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape

Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and LandscapeAfter the Barbarian sacks of Rome around 400-500 AD, which signalled the beginning of the end of the Roman Empire amid widespread upheaval, the chestnut pollen percentage then drops temporarily. This decrease suggests that many of the Roman-era orchards were abandoned, Krebs says, probably not only due to the fall of the Roman Empire, but also, because a wider population decline in many areas at the time.

“Juglans [walnut] has a different pattern,” says Krebs. The spread of pollen from these trees is less clearly associated with the rise and fall of the Roman empire, he and his colleagues found. Its distribution around Europe had already increased before the arrival of the Romans, perhaps pointing to the ancient Greeks and other pre-Roman communities as playing a role.

But while the Romans can perhaps take credit for spreading the sweet chestnut around mainland Europe, some separate research suggests they were not behind the arrival of these trees in Britain. Although the Romans have previously been credited with bringing sweet chestnuts to the British isles – where they are still a key part of modern woodlands – research by scientists at the University of Gloucestershire in the UK found the trees were probably introduced to the island later.

This speedy regrowth came in handy given the Romans’ constant need for raw materials for their military expansion

Sweet chestnut trees can be striking features of the landscape. They can grow up to 35m (115ft) tall and can live for up to 1,000 years in some locations. Most of those alive today will not have been planted by the Romans, but many will be descendants or even cuttings taken from those that ancient Roman legionnaires and foresters brought with them to the far-flung corners of the empire. The oldest known sweet chestnut tree in the world is found in Sicily, Italy, and is thought to be up to 4,000 years old.

Wood for fortresses

Why did the Romans so favour the sweet chestnut tree? According to Krebs, they did not tend to value the fruit much – in Roman culture, it was portrayed as a rustic food of poor, rural people in Roman society, such as shepherds. But the Roman elites did appreciate sweet chestnut’s ability to quickly sprout new poles when cut back, a practice known as coppicing. This speedy regrowth came in handy given the Romans’ constant need for raw materials for their military expansion.

“Ancient texts show that the Romans were very interested in Castanea, especially for its resprouting capacity,” he says. “When you cut it, it resprouts very fast and produces a lot of poles that are naturally very high in tannins, which makes the wood resistant and long-lasting. You can cut this wood and use it for building fortresses, for any kind of construction, and it quickly sprouts again.”

Coppicing can also have a rejuvenating effect on the chestnut tree, even after decades of neglect.

In Ticino, chestnut trees became more and more dominant under the Romans, according to the pollen record. They remained popular even after the Roman Empire fell, Krebs says.

One explanation for this is that locals had learned to plant and care for the tree from the Romans, and then came to appreciate chestnuts as a nourishing, easy-to-grow food – by the Middle Ages, they had become a staple food in many parts of Europe. The chestnuts, for example, could be dried and ground into flour. Mountain communities would also have welcomed the fact that the trees thrived even on rocky slopes, where many other fruit trees and crops struggled, Krebs adds.

“The Romans’ achievement was to bring these skills from far away, to enable communication between people and spread knowledge,” he says. “But the real work of planting the chestnut tree orchards was probably done by local populations.”

When they are cultivated in an orchard for their fruit, sweet chestnut trees benefits from management such as pruning dead or diseased wood, as well as the lack of competition, all of which prolong their life, Krebs says: “In an orchard, there’s just the chestnut tree and the meadow below, it’s like a luxury residence for the tree. Whereas when the orchard is abandoned, competitor trees arrive and take over.”

Research on abandoned chestnut orchards has shown that when left alone, chestnut trees are crowded out by other species. In wild forests, “Castanea reaches a maximum age of about 200 years, then it dies,” Krebs says. “But here in Ticino, where chestnuts have been cultivated, they can reach up to almost 1,000 years, because of their symbiosis with humans.”

By the end of the Roman era, the sweet chestnut had become the dominant tree species in Ticino, displacing a previous forest-scape of alders and other trees, the pollen record shows: “This was done by humans. It was a complete reorganisation of the vegetal landscape,” Krebs explains.

In fact, pollen evidence from a site in Ticino at some 800m (2,625ft) above sea level shows that during the Roman period there was a huge increase in Castanea pollen, as well as cereal and walnut-tree pollen, suggesting an orchard was kept there, Krebs says.

By the Middle Ages, long after the Romans were gone, many historical texts document the dominance of sweet chestnut production and the importance of foods such as chestnut flour in Ticino, says Krebs. “In our valleys, chestnuts were the most important pillar of subsistence during the Middle Ages.”

People in Ticino continued to look after the trees, planting them, coppicing them, pruning them and keeping out the competition, over centuries, Krebs says: “That’s the nature of this symbiosis: humans get the fruit [and wood] of the chestnut tree – and the chestnut gets longevity”, as well as the opportunity to hugely extend its natural area of distribution, he explains.

A similar transfer of chestnut-related knowledge to locals may have happened elsewhere in the Roman Empire, he suggests – and possibly left linguistic traces. As a separate study shows, across Europe, the word for “chestnut” is similar to the Latin “castanea” in many languages.

Today, Europe’s sweet chestnut trees are facing threats including disease, climate change and the abandonment of traditional orchards as part of the decline in rural life. But chestnut trails and chestnut festivals in Ticino and other parts of the southern Alps still celebrate the history of sweet chestnuts as a past staple food – reminding us of the long legacy of both Roman and local ideas and skills in tree-care.