Climate change: Is the UK on track to meet its targets?

The UK has pledged to reduce its greenhouse-gas emissions to net zero by 2050. Net zero means a country takes as much of these climate-changing gases – such as carbon dioxide – out of the atmosphere as it puts in.

The UK’s target is important to meet its commitments under the 2015 Paris climate agreement in which governments agreed to try to limit global temperature rises to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

However, in July 2022, the High Court ruled that the government’s net zero strategy failed to outline policies that would enable it to meet the target. As a result the government published a new plan.

Currently, less than 40% of the UK’s required emissions reductions are supported by proven policies and sufficient funding, according to the Climate Action Tracker website.

So, what progress is the government making?

The government says all of the UK’s electricity will come from clean sources by 2035.

The government is expecting a 40-60% rise in demand for electricity by 2035, for example due to the electrification of transport. This means taking the carbon emissions out of electricity generation is important.

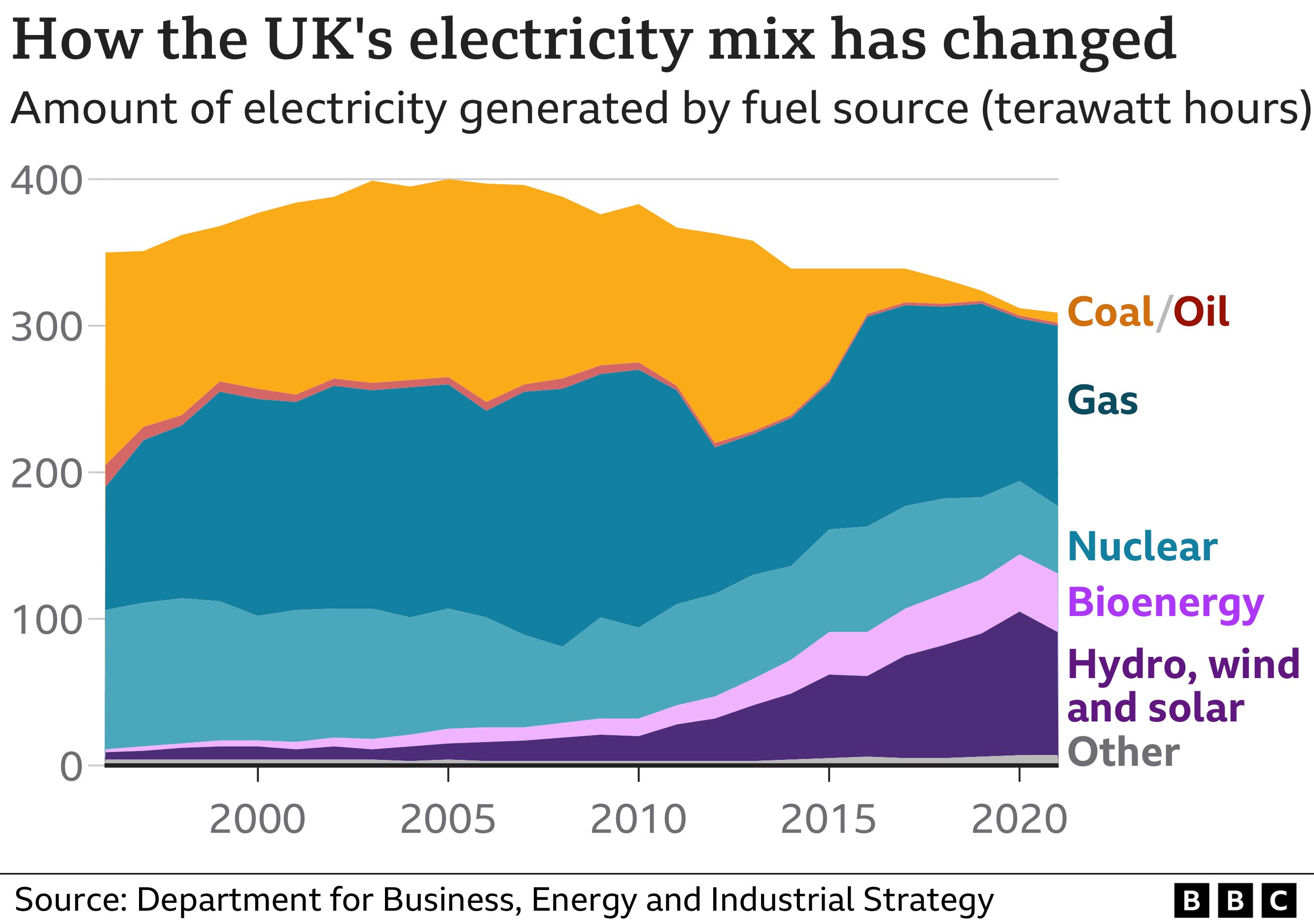

UK governments have been relatively successful in cutting emissions from electricity generation. These fell by 73.4% between 1990 and 2021.

This is largely due to a substantial reduction in electricity generated from coal – the dirtiest fossil fuel – from 40% in 2012 to less than 2% last year.

The proportion of electricity generated by renewables has grown to around 40% in the last few years, up from just over 10% a decade ago. Fossil fuels – mainly natural gas – still generate about 40% of UK electricity. The remainder comes from nuclear power and imports.

The government has set ambitious targets to accelerate the expansion of low carbon energy to reduce reliance on natural gas. These include increasing offshore wind capacity five-fold by 2030 and approving up to eight new nuclear reactors.

A report by the National Audit Office warned that the lack of a clear delivery plan risked the UK not meeting its 2035 carbon-free electricity target. But the UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) recently emphasised that it is still possible if delivery is significantly ramped up.

However, the government has opened a new licensing round for companies to explore for oil and gas in the North Sea for wider energy production, not limited to electricity. The International Energy Agency warns this would go against climate agreements.

Direct emissions from buildings account for about 17% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions, mainly due to burning fossil fuels for heating.

The government committed to installing 600,000 heat pumps a year by 2028 to replace gas boilers. Heat pumps use electricity rather than gas, and are three times more efficient than a boiler. The government is offering grants of £5,000 to help homeowners install a heat pump.

However, in February 2023, the Lords Climate Change Committee described this scheme as “seriously failing”. Currently, only 50,000 heat pumps are installed annually, meaning the government’s 600,000 target is “very unlikely to be met”.

Insulation is one of the most effective ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from housing. It prevents the loss of heat, meaning less energy is wasted trying to maintain the house’s temperature.

However, the UK has some of the least energy-efficient homes in Europe. In June, the CCC said there was a “shocking gap in policy for better insulated homes”.

In response, in November 2022 the government announced a new £1bn scheme, called ECO+, to improve insulation in UK homes. This is due to come into effect in April 2023. But critics say it doesn’t go far enough.

In March 2023 the government rebranded it as the Great British Insulation Scheme, to help insulate 300,000 of the poorest performing homes.

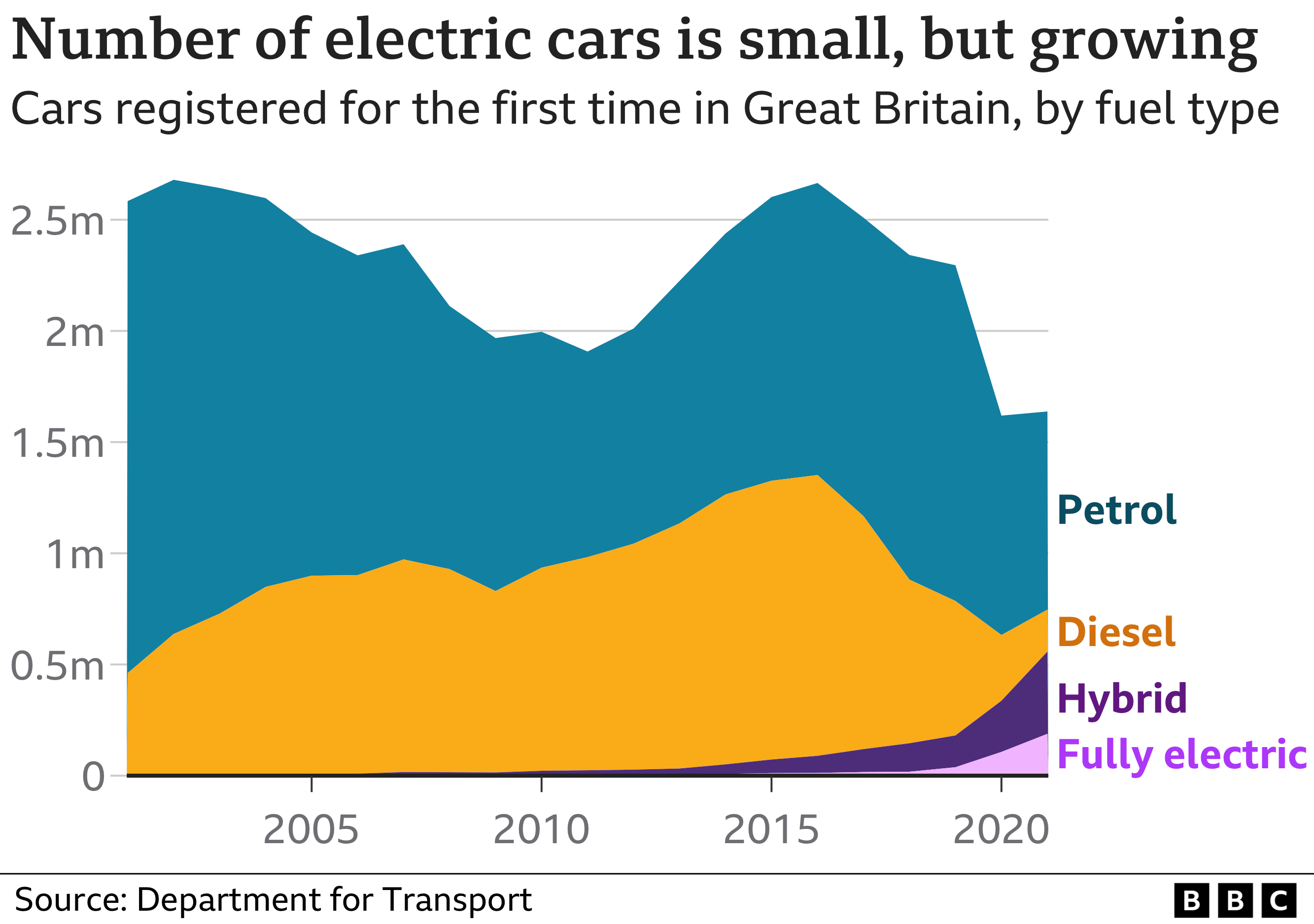

Transport accounted for just over a quarter of UK emissions in 2021, making it the largest emitting sector.

The government says no new petrol and diesel cars will be sold from 2030.

By 2028, it wants 52% of car sales to be electric. In 2021, 11.6% of car sales were electric. The CCC says that this is ahead of schedule and that the market is “currently growing well”.

To meet higher demand, the government wants 300,000 publicly-accessible charging points by 2030. This represents more than a ten-fold increase from present levels. It has pledged over £350m to fund charging infrastructure.

In June 2022, the government announced it was ending grants for electric cars, saying the payment was having “little effect on rapidly accelerating sales”.

In March 2022, it pledged £200m for nearly 1000 new electric and hydrogen buses, and is consulting on an earlier phase-out date of non-zero-emissions buses between 2025 and 2032.

And it aims to remove all diesel-only trains by 2040, but the CCC says it needs a clearer plan to achieve this.

It has promised to double cycling rates from 2013 levels by 2025, and build a “world-class” cycling network by 2040. It has spent £338m on walking and cycling infrastructure in England

Flying makes up about 7% of overall UK emissions, and shipping about 3%.

The UK published its strategy for delivering net zero aviation by 2050 in July 2022.

It was criticised for relying too much on technologies such as sustainable fuels and zero emissions aircraft that do not yet exist. It also relies on the development of ways to remove CO2 from the atmosphere to make up for remaining emissions in 2050.

As a result, the CCC said that the government should be looking at how to manage demand and not allow it to grow.

The government has announced £77m of funding to help decarbonise shipping.

Agriculture is the source of 11% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The CCC said emissions from agriculture needed to be cut by 30% between 2019 and 2035.

This would require eating 20% less meat and dairy by 2030 and shifting land from agriculture to supporting trees and restoring peatlands.

The CCC criticised the government’s food strategy for failing to deliver action to drive down emissions from agriculture at the required scale or pace.

The National Food Strategy independent review shows daily meat consumption in the UK has fallen by 17% in the last decade. The government has been criticised for not pushing for further behavioural change in meat consumption.

In February 2023, the government released details of its long-awaited environmental land management schemes, replacing the EU common agricultural policy.

Trees and peatlands play important roles in removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

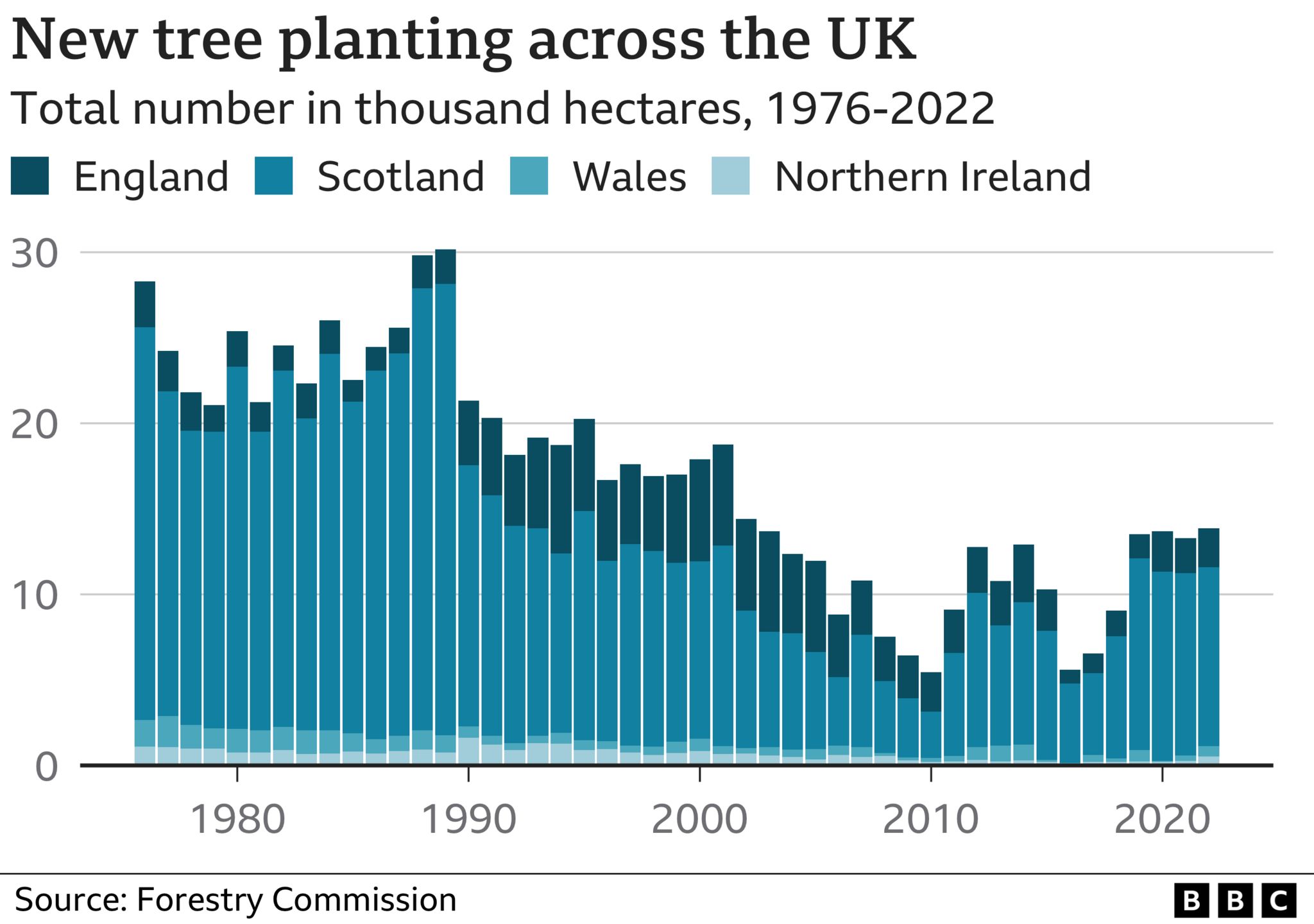

UK forest cover is 13%, among the lowest in Europe.

The government has pledged to end deforestation in the UK by 2030. It has an ambitious target to plant 30,000 hectares of trees a year by 2025.

However, annual tree planting has not risen above 15,000 hectares UK-wide since 2001. In June 2022, the UK forestry body warned that there was “zero chance” of the UK meeting its target.

It is estimated that only around 20% of UK peatlands are in a near-natural state, including only 1.3% in England. These damaged peatlands are responsible for 5% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions, whereas healthy peatlands would take up carbon dioxide.

The government aims to restore 35,000 hectares of peatland by 2025, and will completely ban the sale of horticultural peat by 2030. However, the CCC warns this does not go far enough.

Hydrogen is a low-carbon fuel that could be used for transport, heating, power generation or energy storage.

The government says it is committed to developing the UK’s low carbon hydrogen capabilities and considers it a critical part of energy security and decarbonisation. It wants to have a 10GW hydrogen production capacity by 2030.

The industry is in its infancy, and the government admits it will need “rapid and significant scale-up” in the coming years.

A recent study warned that hydrogen was less efficient and more expensive for heating homes than alternatives such as heat pumps.

The government has promised a decision on the role of hydrogen in heating by 2026. In March 2023 it announced the first winning projects from the £240m Net Zero Hydrogen Fund.

In December 2022, it launched a consultation on the potential for hydrogen transport.

The ability to capture carbon before it is released – or take it out of the atmosphere and store it – will be important if the UK is to reach net zero, to balance emissions from the continued limited use of natural gas.

The government is aiming to capture and store between 20 and 30 million tonnes of CO2 a year by 2030.

In March 2023 it announced the first sites for storing captured carbon, which will be on Teesside.

The Chancellor recently announced £20bn in investment in carbon capture over the next 20 years. But the technology is still emerging and is expensive.

Emissions from manufacturing and construction represent about 12% of total UK emissions.

The government aims to cut emissions from manufacturing by about two-thirds by 2035.

It has awarded £34.8m of funding through the Industrial Energy Transformation Fund to help energy-intensive industries decarbonise, but critics say this is insufficient.

The government also plans to cap the amount of emissions allowed by individual sectors each year, reducing that amount over time.

But the scheme risks companies shifting production to other countries and therefore not reducing their emissions.