Africa unmasked at the Tate: The continent through its own lens

A remarkable new exhibition showcasing contemporary African photography – looking at Africa’s past, present and future through the lenses of artists from the continent – has opened in London.

One of the largest exhibitions of its kind ever staged, this thrilling new collection at the Tate Modern features beautifully powerful photographs, videos and installations that capture the essence of the realities of the fastest-growing continent in the world.

It eschews a view of Africa that has historically been defined by Western images.

British-Ghanaian curator Osei Bonsu has taken a thematic approach to explore the complex diversity of the vast continent through the eyes of 36 artists from Africa and its diaspora.

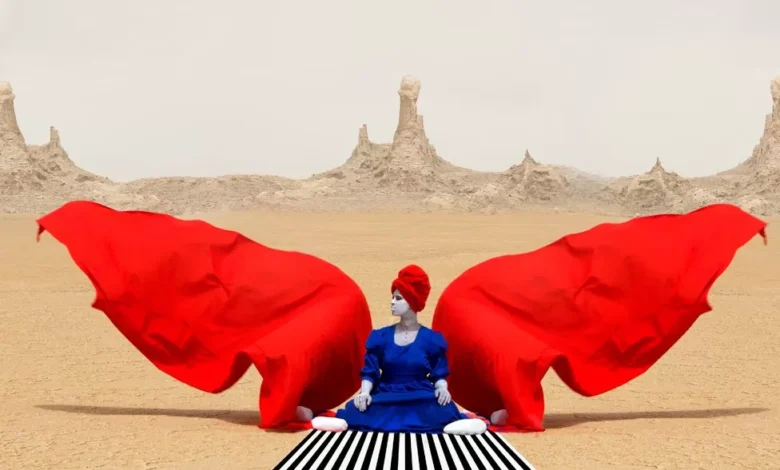

These include legendary artists such as Malawi’s Samson Kambalu and Ghanaian James Barnor, and new talents like Aïda Muluneh from Ethiopia, whose work Star Shine is above, and Ruth Ossai, who grew up in Nigeria and Yorkshire, in northern England.

Bonsu has divided the more than 150 works on show into three “chapters”: identity and tradition, counter histories and imagined futures, taking the viewer on a thrilling journey from Kinshasa’s bustling streets to the deserts of Mauritania.

The show uses photography, video and installation to map out the possibilities of Africa in exquisite, complex, revealing ways.

The task of distilling the complexity and diversity of this expansive continent is no small feat. But through his deft curation, Osei has pulled off a visual feast, creating a vivid tapestry that thrusts contemporary African art firmly into the global centre.

Speaking to the BBC, he explained how his thematic approach allows examination of how the continent’s “shared histories” – from its colonial experience to post-independence revolutionary movements and its urban future – had “shaped and reshaped” how people in Africa see themselves and their place in the world.

The exhibition’s title, A World in Common, is inspired by the work of the pioneering Cameroonian historian and intellectual Achille Mbembe, who argued that we must think of the world from an African perspective. His ideas provide the intellectual thread that runs through the exhibition, offering a bold invitation to reconsider how we view the place of Africa in the world.

By featuring many artists for the first time internationally, the Tate Modern puts emerging African talent centre stage in a museum so crucial in setting the world’s artistic agenda.

One artist featured is the British-Nigerian, Zina Saro-Wiwa. Her work, The Invisible Man Series, 2015, explores the tradition of mask-wearing among the Ogoni, her ancestral ethnic group in the Niger Delta of Nigeria.

Her work unpacks the role masks traditionally play in Ogoni culture and is also an ode to a more personal and emotional journey. “I made this work to help me heal myself,” she told the BBC.

Her intimate, mournful and beautiful images demonstrate the power of art to bridge the past and the present, the group and the individual.

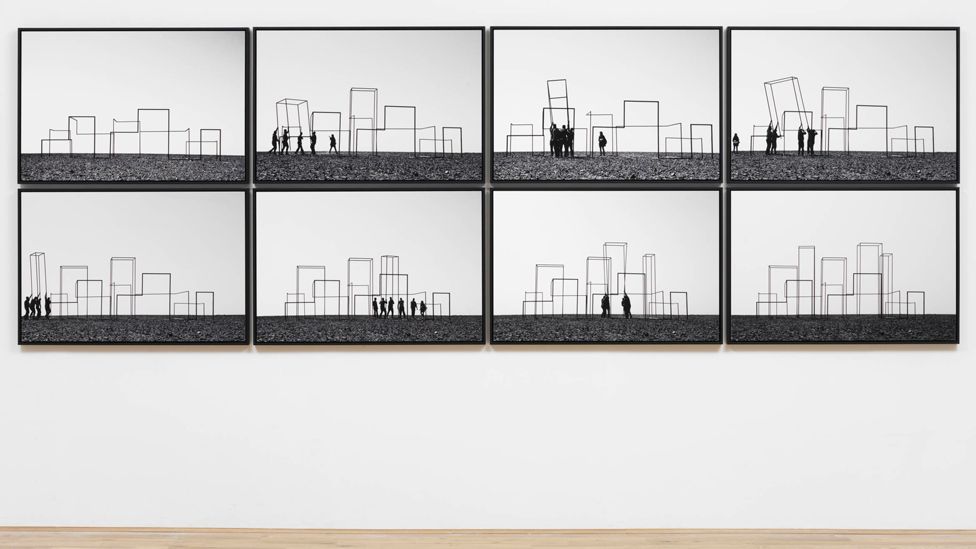

Another artist shown is the Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda, whose work titled Rusty Mirage (The City Skyline), 2013, is a series of photographs of sculptures he created in the Jordanian desert.

These sculptures look like the outlines of cities emerging from barren desert lands. Inspired by the cityscapes of Dubai and Luanda, the capital of Angola and the city of his birth, Kiluanji told the BBC that he was interested in exploring the “idea of emptiness”.

He explains how Luanda, wrecked by one of Africa’s longest civil wars, from 1975 to 2002, was reimagined as a city of glistening towers.

He says many buildings have gone up unfinished in Luanda, but these buildings are “monuments to greed and corruption”.

Another featured artist is Eritrean-Canadian Dawit L Petros, whose work speaks powerfully of the perilous migration journeys taken by many young people across Africa.

His images highlight the contrast between Mauritania and the Italian island of Sicily, shedding light on the intricate realities of migration.

This is just the beginning for Osei, who hopes someday that an exhibition like this could travel to Africa and beyond.

For now, he wants this dazzling show to “inspire” those on the continent and elsewhere to look with African eyes.

Ismail Einashe is a freelance journalist based in London and Nairobi and the author of Look Again: Strangers, a book exploring migration through the lens of art.