The story behind City Lights and cinema’s greatest ever final shot

Ninety-five years after its release, Charlie Chaplin’s silent comedy, City Lights, is often cited as one of the greatest films ever made – and its final moments are key to its reputation.

When Charlie Chaplin was asked by Life Magazine in 1966 which of his films he regarded as his favourite, he gave the honour to City Lights, before downplaying his achievements with, “I think it’s solid, well done.”

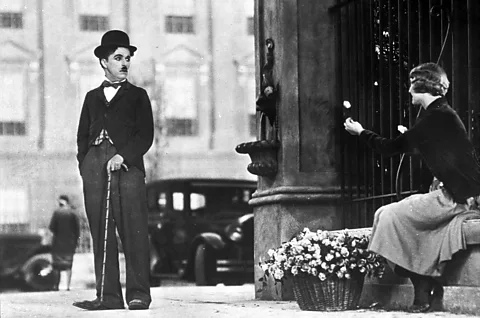

Since its premiere at the Los Angeles Theatre on 30 January 1931, cinephiles and film-makers have heaped slightly more effusive praise on the silent romantic comedy, in which Chaplin’s Tramp character falls in love with a blind flower girl (Virginia Cherrill), who mistakes him for a millionaire.

When the British Film Institute released the first of its renowned lists of the greatest films of all time in 1952, City Lights came joint second alongside Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925). Stanley Kubrick, Orson Welles, and Andrei Tarkovksy each named it as one of their favourite films, while The Night of the Hunter screenwriter James Agee wrote that it contained the “greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies”.

The moment in question from comes right at the end of City Lights. Finally reunited with the flower girl, who can now see, the Tramp stares at her lovingly, as the camera fades to black.

It’s a shot of such pure emotion and simple poignancy that it is regularly cited as the greatest ending in cinematic history. In the 95 years since City Lights’ release, numerous films have tried to replicate its subtle artistry and the power of its performances.

Years of creative toil and suffering went in to making the final sequence, which only works because the final act of City Lights sets it up so well. After the Tramp learns the flower girl is going to be evicted from her apartment, he works as a street sweeper, then a boxer. Eventually he gets the money from a drunk millionaire who forgets him when he’s sober – and accuses the Tramp of stealing from him. Just before the Tramp is arrested, he gives the funds to the flower girl. She is able to pay her rent and see a doctor who can cure her blindness.

Months later, when the Tramp is released from prison, he discovers she now has vision and is running her own, very successful flower shop. The tattered Tramp appears outside it. When she finally recognises him, a look of deep affection appears on her face. He smiles back, as the film comes to an end.

‘It was so pure’

Charles Marland, who wrote the BFI Classics book celebrating City Lights, believes its final scene is the definitive example of Chaplin’s mastery as a film-maker. “He knew how to frame the shots to intensify the emotional effect of the scene. The camera tightens from a medium to a close-up,” he said, before noting that Chaplin once said he used long shots for comedy, and close-ups for tragedy and drama. “Then there’s the soundtrack, which is complex, emotional, and provokes an intellectual response.”

All of this would be for nothing without the performances from Chaplin and Cherrill, who rather remarkably made her film debut with City Lights. After shooting several takes of their final exchange, Chaplin felt they were going overboard, overacting and over-feeling it, says Marland. So Chaplin decided that the Tramp should just look at Cherrill with more intensity. According to Marland, Chaplin once described filming the sequence as “a beautiful sensation of not acting. Of standing outside of myself. The key was being slightly embarrassed, delighted about meeting her again, apologetic without getting emotional. [The Tramp is] watching and wondering what she is thinking. It was so pure.”

Years after City Lights’ release, Cherill told Jeffrey Vance, the author of Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema, that Chaplin usually had dry skin, but she felt his palm get moist as they got closer to the required performance. “She knew something was happening to him that was unusual,” Vance tells the BBC. “That she was giving him what he wanted and he was reacting differently. He was reacting as the character.”

One vital reason why City Lights has continued to resonate over the decades is Chaplin’s decision to cut away before we get a conclusive ending. Romantics will maintain that, despite his shabby look and lack of money, the flower girl accepts the Tramp after what he did for her. But there are others who believe that there’s no chance of her going off into the proverbial sunset with him.

“I don’t think it’s romantic at all,” says Vance. “We see her vanity when her sight is restored. She looks in the mirror. Fusses with her hair. She is disappointed the wealthy man is not him. When she first sees the Tramp, she giggles, and gives him money out of pity.” By going from overjoyed, terrified, ashamed, to excited, Chaplin’s performance in those final moments is so layered and subtle that it leaves it to viewers to decide what happens next.

Simply the best?

There are, of course, many rival claimants to the title of the greatest final shot in cinema history. Planet of the Apes’ Statue of Liberty sighting, the slow realisation in The Graduate, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’s freeze-frame finish, the door closing in The Godfather, and Norma Desmond asking for her close-up in Sunset Boulevard each deserve a mention. But none of these has been replicated quite as often as City Lights’ final moment.

Films as diverse as The 400 Blows, This Is England, Gone Girl, and Moonlight owe Chaplin a debt, as they each end with characters staring down the camera. Several films have been much more overt with their homages. Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979) ends with his character ruefully smiling at his young girlfriend Tracy, after she confirms she’s going to London for six months. A year later, in The Long Good Friday, director John Mackenzie focused on Bob Hoskins’ gangster going through a variety of emotions in quick succession as he realises he’s been caught by IRA assassins and is going to be killed.

Even the end of Pixar’s Monsters, Inc. tips its animated hat to City Lights. Rather than showing Sulley’s reunion with Boo, after the pair were seemingly separated forever when the portal into her bedroom was destroyed, we just see him opening her door, looking around, hearing Boo say, “Kitty!” and smiling.

As is so often the case, brevity makes these moments even more powerful. But it still takes hours of creativity, skill, and talent – as well as thousands, sometimes millions, of dollars – to put these scenes on celluloid. That was especially true of City Lights. Not only was it Chaplin’s most expensive film – with production costs of $1.5m (around $30m or £22m today) – but he spent years crafting the story, shooting it, and hoping it would live up to immense expectations that met his work.

A labour of love

When cameras started rolling on City Lights on 27 December 1928, Chaplin was the most famous man in the world. He’d risen from London squalor to become a multimillionaire who had complete creative control over his films. So much so that, even though The Jazz Singer had become the first talking picture 14 months earlier, and Hollywood was no longer interested in silent films, Chaplin insisted that City Lights would have no lines of dialogue.

City Lights’ beauty is in its simplicity. Chaplin knew simplicity was very difficult to achieve – Jeffrey Vance

He was very adamant that the Tramp was a creature of the silent film,” says Vance. “But he also knew he needed to make a perfect film. He felt that was the only way an audience was going to accept a silent film.” Chaplin was so concerned with making City Lights as flawless as possible that he spent a year in pre-production and filming lasted all the way through until September 1930.

The Tramp’s first meeting with the flower girl, where she mistakes him for a millionaire, plagued Chaplin to such an extent that it still holds the Guinness World Record for the most retakes for a single scene. He eventually shot the sequence 342 times. Chaplin’s creative toil was worth it. City Lights went on to make three times its budget at the box office and was met with rave reviews, while its reputation has only improved with time.

In the decades since, despite Modern Times’ biting satire, The Great Dictator’s rousing ending, and The Gold Rush’s iconic comedic set pieces, City Lights has proven to be Chaplin’s most enduring and endearing film. “Like Dickens novels and Shakespeare plays, Chaplin films go in and out of fashion,” says Vance. “But City Lights’ beauty is in its simplicity. Chaplin knew simplicity was very difficult to achieve.”

The power and poetry of City Lights is best summed up by its final image of a hopeful Tramp smiling and dreaming of a brighter future, which – nearly 100 years and tens of thousands of “talkies” later – no other ending has yet come close to matching. “That’s why Chaplin was a genius,” says Vance. “That’s why he was in a class by himself.”