How long until a robot is doing your dishes?

Imagine the biggest market for a physical product you can. Are you thinking of mobile phones? Cars? Property?

They are all chunky markets but in the coming decades a new product will be rolled out that will dwarf those giants, says Geordie Rose, the chief executive of Sanctuary AI.

The Vancouver-based firm is developing a humanoid robot called Phoenix which, when complete, will understand what we want, understand the way the world works and have the skills to carry out our commands.

“The long term total addressable market is the biggest one that’s ever existed in the history of business and technology – which is the labour market. It’s all of the things we want done,” he says.

Before we get too ahead of ourselves, he qualifies that statement: “There is a long way to go from where we are today.”

Mr Rose is unwilling to put a time frame on when a robot might be in your house, doing your laundry or cleaning the bathroom. But others I have spoken to in the sector say it could be within ten years.

Dozens of other firms around the world are working on the technology.

In the UK, Dyson is investing in AI and robotics aimed at household chores.

Perhaps the highest profile company in the market is Tesla, Elon Musk’s electric car company.

It is working on the Optimus humanoid robot, which Mr Musk says could be on sale to the public in a few year’s time.

We will see whether that turns out be the case. What we can say now is that leaps forward in artificial intelligence mean the development of humanoid robots is accelerating.

“Ten years at the pace the technology is moving now is is an eternity. You know, every month, there’s new developments in the AI world that are like fundamental change,” says Mr Rose, who has a background in theoretical physics and previously founded a quantum computing company.

Mainstream interest in AI exploded late last year when a powerful version of ChatGPT was made public. Its ability to generate all sorts of useful text and images has spawned rivals and a wave of investment in AI tech.

But developing the AI that would allow a robot to complete useful tasks is a different and more difficult task.

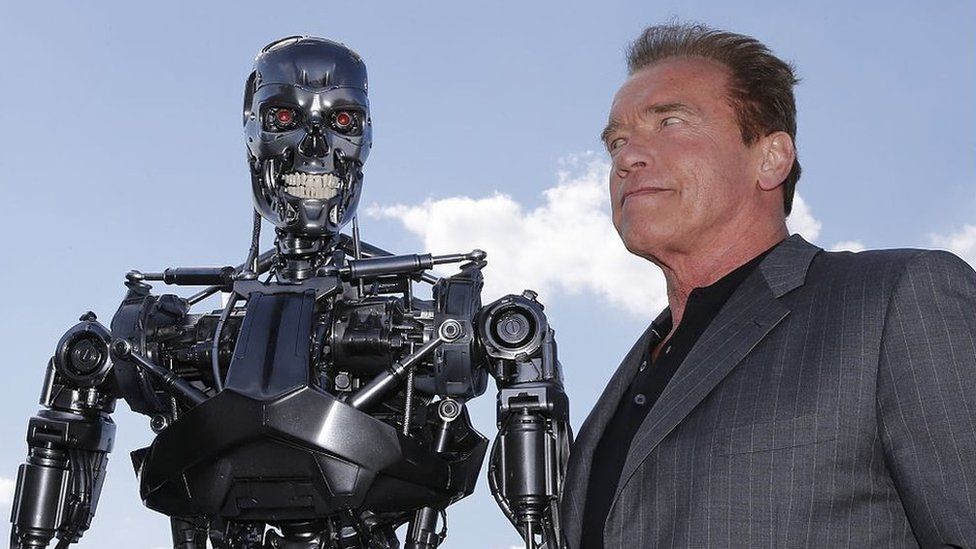

Unlike ChatGPT and its rivals, humanoid robots have to navigate the physical world and need to understand how objects in that world relate to each other.

Tasks that seem easy to many humans are major feats for humanoid robots.

For example, in a trial project, Sanctuary’s robot Phoenix has been packing clothes into plastic bags in the backroom of a Canadian shop.

“This is a problem that engages a lot of different complex issues in an AI driven robotics system, because bags are floppy, they’re transparent… there’s a place where they open.

“Usually after you manually open the bag, you have to release one hand and then go and put something in a bag,” says Mr Rose.

“The manipulation of bags is is actually very, very hard for robots,” he adds – a line which makes today’s humanoid robots seem much less scary than some of their Hollywood counterparts.

Sanctuary has a system for training Phoenix on specific tasks like bag packing. In partnership with a business, it will film a particular task being done and then digitise the whole event.

That data is used to create a virtual environment which, as well as containing all the objects, simulates the physics including gravity and resistance.

The AI can then practise the task in that virtual environment. It can have a million attempts and when the developers think the AI has mastered the event in the virtual world, it will be allowed to try in the physical world.

In this way Phoenix has been trained to do about 20 different roles.

Mr Rose sees this as the way forward for humanoid robots – mastering specific tasks that will be useful for business. A robot that can do household chores is much further down the line.

One of the biggest challenges is to give the robot a sense of touch, so it knows how much pressure to apply to an object.

“We have a facility with these types of tasks that comes from an evolutionary heritage, that’s like a billion years long… they’re very hard for machines,” says Mr Rose.