The indigenous groups fighting against the quest for ‘white gold’

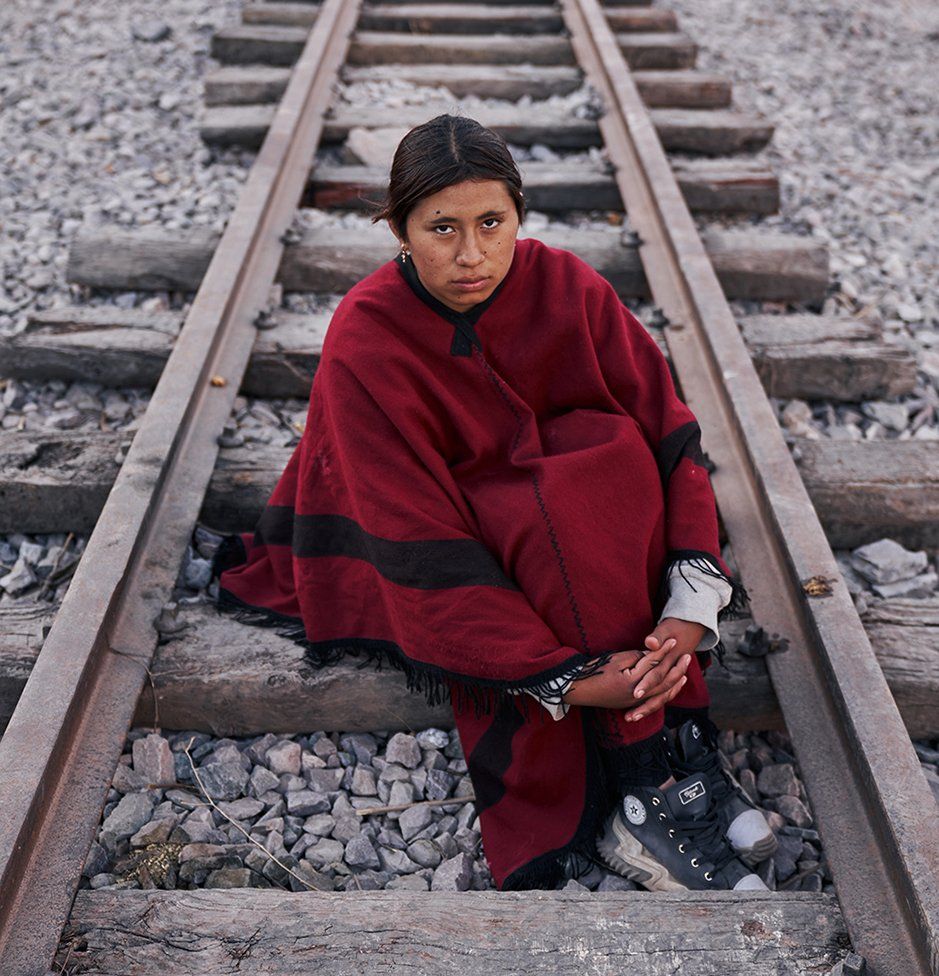

“Our land is drying up and our water is polluted,” says Nati Machaca, one of the protesters manning a roadblock in the village of Purmamarca, high in the Andes mountains.

Ms Machaca is a spokeswoman for the indigenous groups living in Jujuy, a province in northern Argentina.

Jujuy is located in what has become known as the “lithium triangle”, a stretch of the Andes straddling the tri-border area between Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, which holds the world’s biggest reserves of lithium.

The metal is used to make rechargeable batteries for everything from smartphones to laptops.

It has become especially sought after as electrical cars, which also use lithium in their batteries, are becoming increasingly popular.

Argentina is the world’s number four lithium producer, but some residents of Jujuy say not only are they not benefiting from the industry, but that their way of life is under threat as a result of it.

Lithium extraction requires huge amounts of water – about two million litres per tonne.

And locals like Nati Machaca, who live off the land and raise cattle in this predominantly rural area, fear it is drying the soil and polluting the water.

“If this goes on, we will soon starve and become ill,” she warns.

The position of the more than 400 indigenous groups inhabiting these mountains is complicated by the fact that many lack legal titles to the land where they have lived for centuries – long before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the 1500s.

Ms Machaca is a case in point. She lives on a piece of land her grandfather bought from the landowner he worked for.

“Back then it was all verbal agreements,” she explains, “but there’s no proof”.

She and many like her, who have no legal documents to back up their claims to the land, could now face eviction under a controversial constitutional reform approved in June by the governor of Jujuy, Gerardo Morales.

“[Governor] Morales comes after the land because he knows it’s where the lithium is,” says Ms Machaca.

The new constitution also limits the right to protest, but that has not deterred the indigenous communities, who have blocked the roads to the lithium mines.

Police were deployed to remove them, but the protesters say this made them more united and determined.

“We are not moving. The land is ours, the lithium belongs to us,” they insisted.

In total, there are 38 lithium mining projects in northern Argentina, of which three are already up and running.

Much of the lithium in this area is located beneath salt flats in the form of lithium brine.

In order to reach the underground deposits, companies first have to drill. The brine is then pumped to the surface into artificial ponds, where some of the liquid is allowed to evaporate before the lithium is extracted through a series of chemical processes.

Local communities warn that the impact on the environment of lithium mining is considerable, both because of the huge amounts of water the process requires and the air and water pollution the chemicals used in the extraction can cause.

According to Marie-Pierre Lucesoli though, companies are making great efforts to optimise the use of water, as well as to reduce the use of fossil fuels, with almost all lithium mining plants being planned to work with solar energy.

Ms Lucesoli is the manager of the chamber of mining in neighbouring Salta, a province which is also rich in lithium, and she is adamant that the processes for obtaining lithium are “evolving on a daily basis with the aim of becoming more sustainable”.

But Néstor Jérez, chief of the Ocloya people, remains concerned about the impact current lithium mining is having and future projects could have.

Indigenous groups like the Ocloya seek to live in harmony with Pachamama (Mother Earth), whom they worship in ceremonies.

And it is from her that Néstor Jérez says they draw the strength to oppose the mining projects: “She is the guarantor of life, so we will defend her whatever it takes.”

He is not swayed by the argument put forward by Ms Lucesoli, who says that lithium mining generates local employment, and that with it comes educational and training opportunities.

“Wealth is not only about the economic improvement of the inhabitants, but also about the improvement of the quality of life that will last for many generations,” she says.

Feeling their concerns were not being addressed, the indigenous groups set off on a march to the capital, Buenos Aires, to make their demands heard by the national government.

The march, called “Malón de la Paz” (Raid for Peace), is modelled on similar indigenous protests held in 1946 and 2006.

Those taking part in this third “Malón de la Paz” say they are determined not to give in until the constitutional reform backed by Governor Morales is revoked.

But they stress that their struggle is much wider than for the land they live on.

“Mining is harming biodiversity and aggravating the climate crisis,” those marching to the capital said.

Meanwhile, Ms Lucesoli argues that lithium will contribute towards curbing climate change, as it is a key element in producing the batteries needed to switch from petrol and diesel cars to electric vehicles. For her, it is part of “the energy transformation to decarbonise the world”.

She does concede though that “the business sector needs to inform the community more” in order to raise awareness among the people who oppose lithium mining.

But those manning the roadblocks in Jujuy and the many who marched to Buenos Aires insist they will not give up their resistance.

“This is not just for us: it’s for the future generations and the entire humanity’s well-being.”