Kitchen shrine serpents and more fascinating new Pompeii discoveries

A kitchen shrine adorned with serpents, a bakery, human skeletons, exquisite frescos, and yes, a picture of something that looks very much like pizza. These are among the new finds being turned up at the Pompeii Archaeological Park.

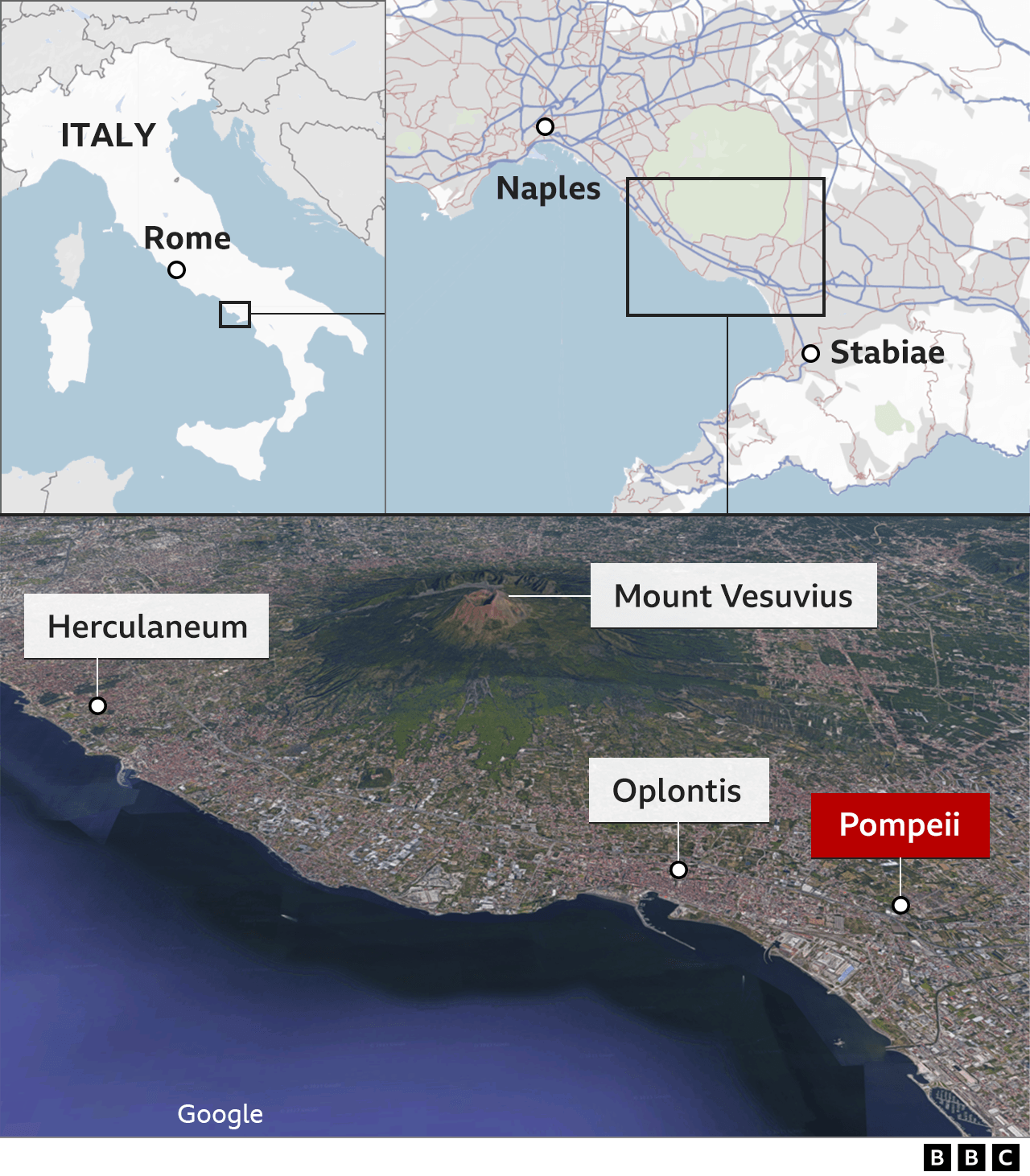

Dig anywhere in the ancient city destroyed by Mount Vesuvius in AD79 and you will unearth a treasure – a snapshot of a lost Roman world.

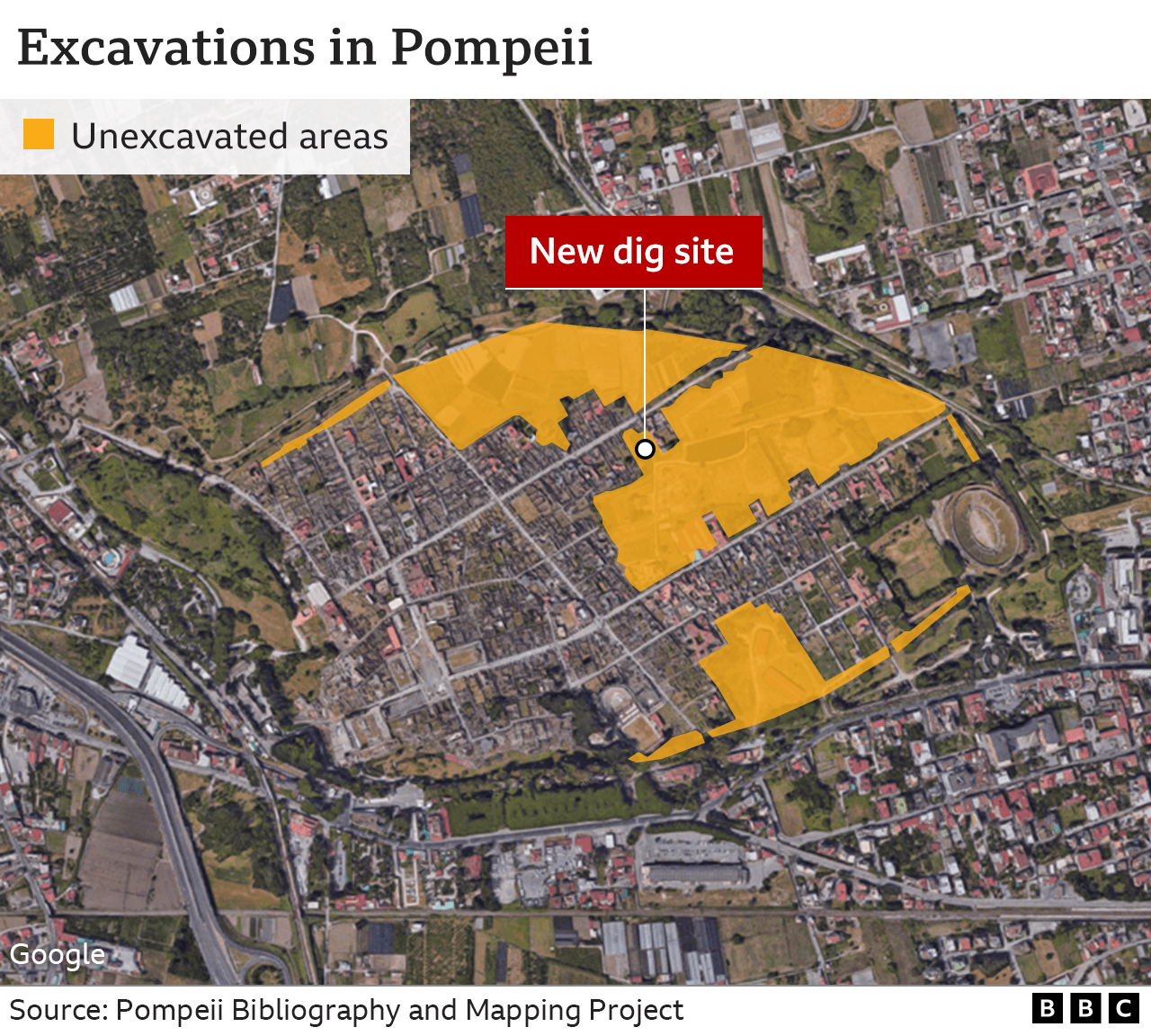

It’s extraordinary to think that one-third of the city buried under pumice and ash has yet to be excavated.

“Much of that will be for future generations,” says Alessandro Russo, the co-lead archaeologist on the new dig.

“We have a problem to conserve what we’ve already found. Future generations may have new ideas, new techniques.”

The latest work returns to a sector in the park last explored in the late 19th Century.

Back then, archaeologists had opened up the frontage of houses on Via Di Nola, one of Pompeii’s main thoroughfares, but hadn’t delved far behind.

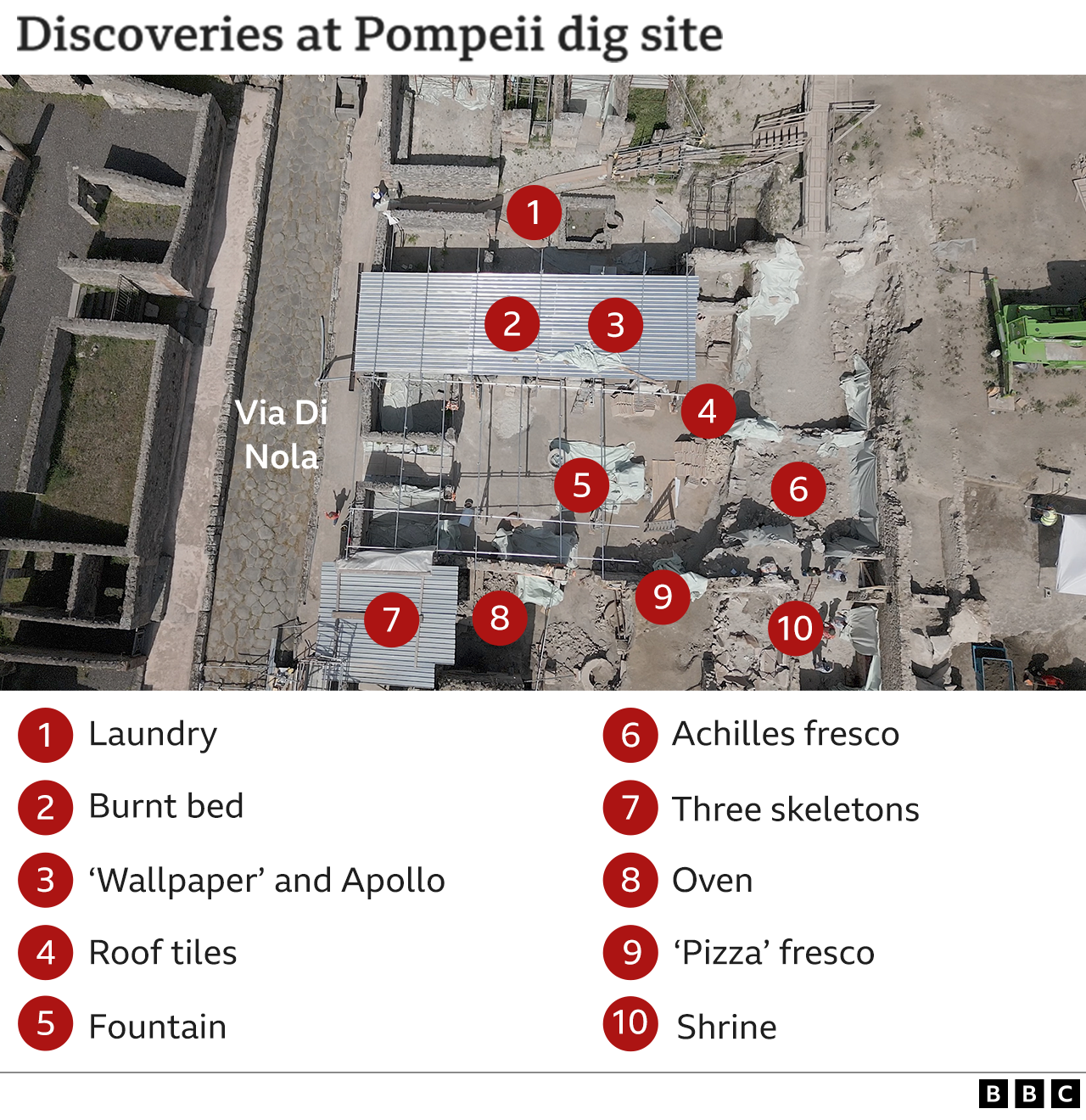

They had identified a laundry but that was about it.

Now, the diggers are progressively pulling away the volcanic ash and pea-sized stones, known as lapilli, that smothered Pompeii during the two catastrophic days of the Vesuvian eruption.

The dig site is, in effect, a whole city block. It is known as an insula and is some 3,000 sq m (32,000 sq ft) in size.

BBC News has been given exclusive access to the investigation with Lion TV, which is making a three-part series to be aired early next year on the BBC.

The oven

“Every room in every house has its own micro-story in the grander story of Pompeii. I want to uncover those micro-stories,” says Gennaro Iovino.

The other co-lead archaeologist wants you to imagine that you are entering a delightful atrium – an entrance hall – with a hole in the roof where lion figureheads direct rainwater down onto a fountain, next to a statue.

The builders were clearly doing some repairs at the time of the eruption because the roof tiles are neatly stacked in two piles. But this is not a magnificent villa, like some of the imposing homes found elsewhere in Pompeii.

This building would have been part-commercial because, on turning right, you are confronted by a giant oven, big enough to be producing 100 loaves a day.

Roughly 50 bakeries have already been found in Pompeii. This, however, can’t have been a shop because there is no shop front.

It’s more likely to have been a wholesaler, distributing bread across town, perhaps to the many fast-food joints for which Pompeii was so famous.

That ‘pizza’

The discovery of a fresco depicting a piece of round flatbread on a silver tray, accompanied by pomegranate, dates, nuts and arbutus fruits, caused a sensation when it was announced to the world in June.

It’s not a pizza, though. Tomatoes and mozzarella, two ingredients in the classic Neapolitan recipe, were not available in Italy in the first century AD.

Perhaps it’s a piece of focaccia? The pizza thing started as a bit of a joke, says Gennaro. “I emailed a picture to my boss, saying ‘first the oven, now the pizza’.”

The world just went crazy after that. A cover will soon be built over the fresco to try to protect it from the elements.

The 20,000 visitors who come to Pompeii every day will demand to see the “ancestor to the pizza”, as some are now describing the fresco subject.

The skeletons

It’s easy to forget that Pompeii was a human tragedy. We have little idea how many died. You have to believe most residents left when they saw the horror unfolding at the top of Vesuvius.

Skeletons have been recovered, perhaps 1,300 to 1,500 in total, and the new dig has its own examples: two women and a child of unknown sex.

Looking at where the victims were found, it’s obvious that they were trying to take cover, hoping that by hiding under a staircase, they would be safe.

What they hadn’t counted on was the roof collapsing from the weight of all the lapilli and ash. The heavy stonework smashed their bodies.

The burnt bed

The drama of those momentous days in October AD79 are also revealed on the other side of the atrium in what was once a bedroom.

The bed itself is a charred mass – caused by a fire. It is barely recognisable apart from its broad outline seared into the walls and floor.

If you look closely at the debris, you can see blackened fragments of the textile bedclothes and even the filling from the mattress.

Archaeologists can tell from the position of these carbonised remains that the fire occurred relatively early in the eruption. They speculate that a lamp might have been knocked over in the panic to get out.

“It would be interesting to understand who were the people that didn’t make it,” wonders park director Gabriel Zuchtriegel.

“Were they the poor? More women than men? Or maybe people who had property and tried to stay to protect what they had, while others who had nothing just took off and ran.”

The shrine

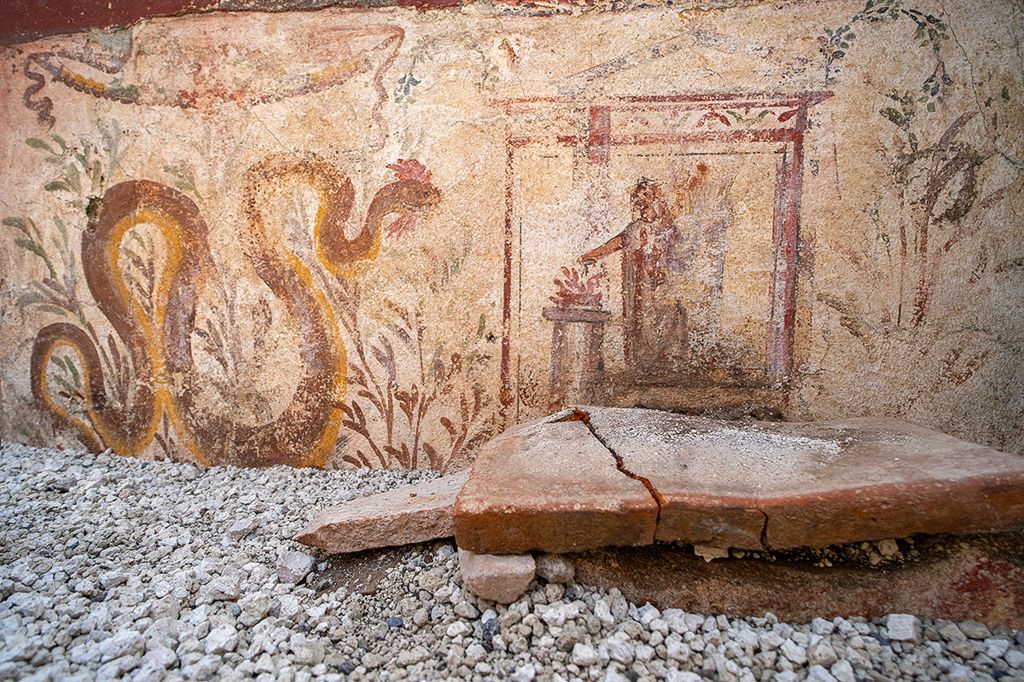

Towards the back of the area so far excavated there is a wall that encloses three rooms. It’s here that the removal of lapilli and ash has exposed more astonishing artwork.

In the middle room, covered by a tarpaulin, is yet another elegant fresco. It shows the episode in the myth of Achilles where the legendary hero soldier – with his unfortunate Achilles heel – tried to hide dressed as a woman to avoid fighting in the Trojan War.

In the third room, I pull back another tarp to reveal a magnificent shrine. Two yellow serpents in relief slither up a burgundy background. “These are good demons,” says Alessandro. He points to a fresco further down the wall just above an opening to a box of some kind.

“This room is actually a kitchen. They would have made offerings here to their gods. Foods like fish or fruits. The snake is a connection between the gods and the humans.”

As the insula is further revealed, scaffolding is being put up around what remains of the buildings to make protective roofing. In the future, the park hopes to erect a high walkway so tourists can see the new treasures that are emerging.

“People sometimes ask [us], ‘What would you like to find? What are you looking for?'” explains Gabriel. He says such questions are misleading.

“What we’re really looking for is what we don’t know. We’re always looking for a surprise. It’s all emerging evidence, leading us somewhere, but we don’t know where that journey goes.”