UK rocket failure is a setback, not roadblock

The failure of the first ever satellite mission launched from UK soil is a setback but not a roadblock to the country’s space plans.

The rocket suffered an “anomaly” late on Monday night after its release by a jumbo jet operated by the American Virgin Orbit company.

The satellites it was carrying could not be released and were lost.

But plans for the UK to become a satellite-launching state are already well advanced.

Launches are planned in Scotland, from Sutherland and Shetland.

These would be the more traditional type of launch system in which the rocket goes straight up from the ground.

The mission had been billed as a major milestone for UK space, marking the birth of a home-grown launch industry. The ambition is to turn the country into a global player – from manufacturing satellites, to building rockets and creating new spaceports.

Deputy CEO of the UK Space Agency, Ian Annett, said it showed “how difficult” getting into orbit actually was – but predicted further launches within the next 12 months.

“It’s still an immense moment of national pride. It would have been the first time that anyone in Europe had managed to put satellites into orbit,” he said.

“We go back, we get up, we do it again, and that defines our future.”

Space consultant Adam Baker, who is independent of the launch team, told BBC News that he believed that the setback would be temporary.

“This is typical early difficult days for a new launch company and a launch from a brand-new site with a number of new staff.

“So, while it is disappointing, it is short term. I think it will get fixed.

“This is the start of a much longer commercial spaceflight journey that the UK is only just starting to make”

Crowds that had gathered on Monday night at Spaceport Cornwall, from where the jumbo jet took off, were deeply disappointed.

“Any kind of failure, it’s how you react to it, so for us it’s to get right back up again,” said Melissa Thorpe, who heads the spaceport. “We’re here to support and get Virgin back up and get another rocket over here in the near future, hopefully, and just keep going.”

It’s clear that Spaceport Cornwall has tried to create a business model that is not solely reliant on Virgin Orbit.

It wants to be a focus for a cluster of space companies, and so far this seems to be working. Its new office centre is over-subscribed. And, of course, the spaceport is just one part of the larger Newquay Airport complex.

Josh Western, CEO of Space Forge, an aerospace company headquartered in Cardiff that lost one of its satellites in the failed launch, told BBC News that he would be prepared to launch from Spaceport Cornwall again with Virgin Orbit.

“We didn’t get to orbit but to see that plane take off with a rocket strapped under its wing, from a very blustery part of Cornwall and ignite that first stage and almost make it… it’s really quite profound that we achieved so much in so little time,” he said.

Mr Western said the trip was meant to test a new way of returning satellites from space to Earth, bringing them back gently enough that the company could for the first time ever re-use and re-launch satellites.

He said the satellite was insured and that the main loss to the start-up company had been in terms of time spent on the project rather than money.

The establishment of the spaceport and the mission have cost roughly £20m. That includes money from local government in Cornwall and national funding through the UK Space Agency.

Shares in Virgin Orbit fell more than 20% in pre-market trading on Tuesday after the failed launch.

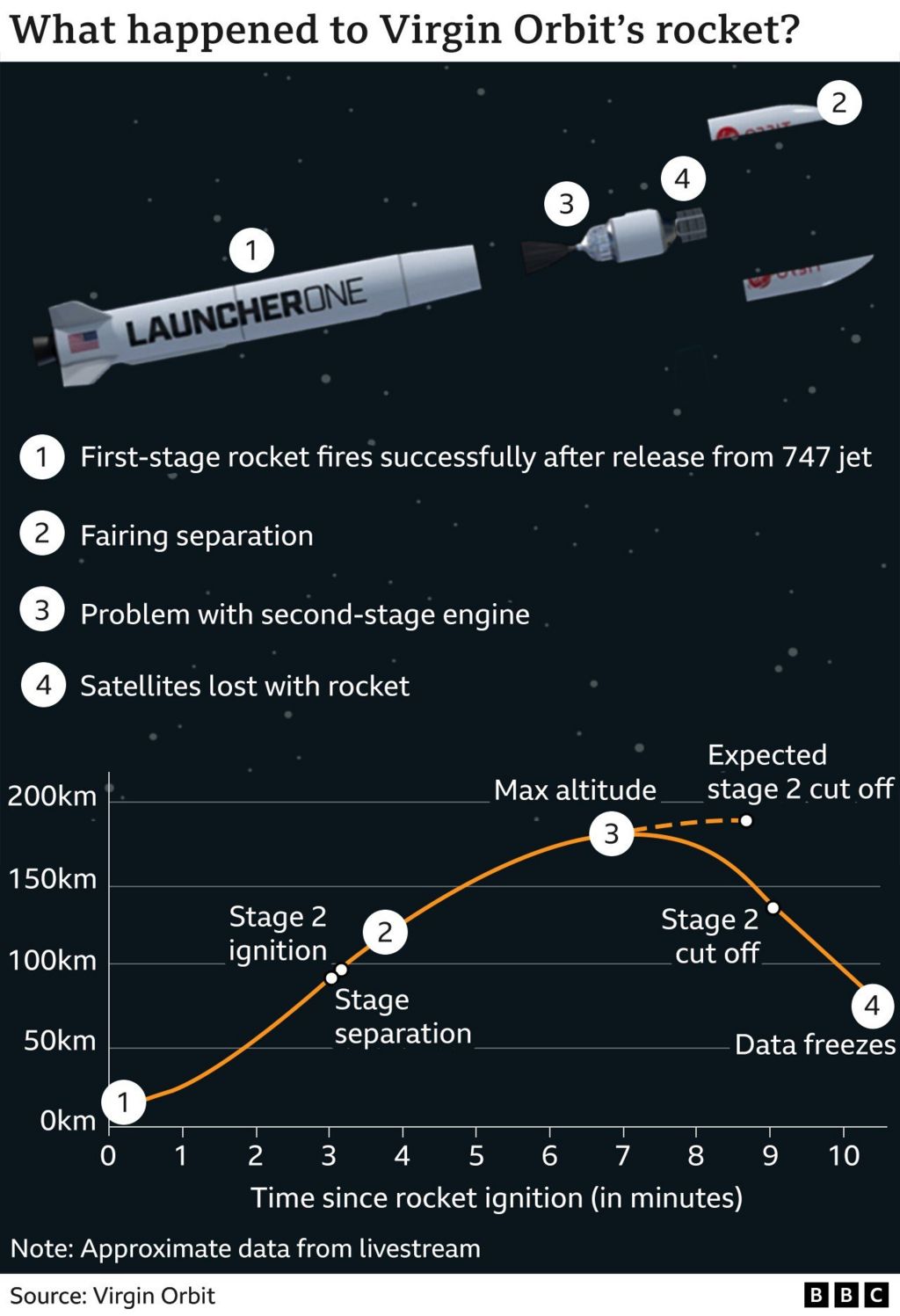

The rocket ignited and appeared to be ascending correctly. But word then came from the company that the rocket had suffered its anomaly.

We’ll have to wait for the official investigation but it’s already apparent the Virgin Orbit rocket ran in to trouble during the engine burn on its upper-stage.

The LauncherOne rocket is a two-stage vehicle, meaning it has two propulsive sections, one that should fire for about three minutes and then fall away, and a second one that should fire for roughly six minutes. A further manoeuvre on the second stage would ordinarily be required to fine-tune the orbit before the satellites are set free to circle the Earth.

The six-minute burn on the upper-stage looks to have been completed, but by its end the rocket was not at the altitude it should have been and seemed to be falling fast. When the data stream eventually froze on Virgin Orbit’s webcast, the vehicle was described as being at only 75km (245,000ft) in altitude.

It’s difficult to judge much on a webcast. The data jumps around a lot as telemetry drops out when the rocket finishes talking to one ground station without yet picking up the next communication point. But Virgin Orbit should have a mass of data to go through to enable engineers to find the cause of the anomaly and to fix it.

The 747 jumbo that carried the rocket to its launch altitude returned to Newquay Airport safely and stands ready to be used on future missions already booked with Virgin Orbit.

The company only managed two flights last year and has a backlog of customers it needs to get into space. It will be looking for a swift return to flight. The Virgin Orbit factory in Long Beach, California, has rockets being produced on a production line.

All the rocket hardware from Monday’s flight – or at least any debris from the mission – is likely now sitting on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. The southward trajectory of the rocket was carefully chosen so that populated areas were avoided in the event of a failure. Warnings were also issued in advance to aircraft and ships to stay clear of obvious danger zones.

The first stage and the rocket fairing – the nosecone that protects the satellites through the thick, lower-reaches of the atmosphere – would have come down off the coast of Portugal as planned anyway. The faulty second stage and those nine small satellites probably returned to Earth somewhere off the coast of Africa.

A Virgin Orbit mission costs in excess of $10m to purchase. This one was bought by the US National Reconnaissance Office and based in the UK so that the American and British governments could fly satellites containing technologies of future interest in the realms of defence and security.

These included advanced radios to track illegal fishers and smugglers at sea. The satellite manufacturers and operators would obviously also have sunk considerable investment into their missions. A number of the payloads were said to be insured, however.

Virgin Orbit is a young company trying to establish itself in the highly competitive launch market.

Customers are acutely sensitive to the price of a launch but even more so to the reliability of the vehicle performing that launch. Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne rocket has now flown six times with two failures.

That’s not unusual in an immature system, but when so many new rockets are coming into the market, a track record of successful launches is what stands out in the crowd. And being a young company, Virgin Orbit is in that growing phase where it’s not currently making money. Quite the opposite. There’s an urgency to get back flying successfully and regularly.