In pictures: Hidden history of Coventry revealed in saved photographs

Rare glimpses of a city’s medieval past and long-gone street scenes have been revealed in a collection of photographs that were saved from destruction.

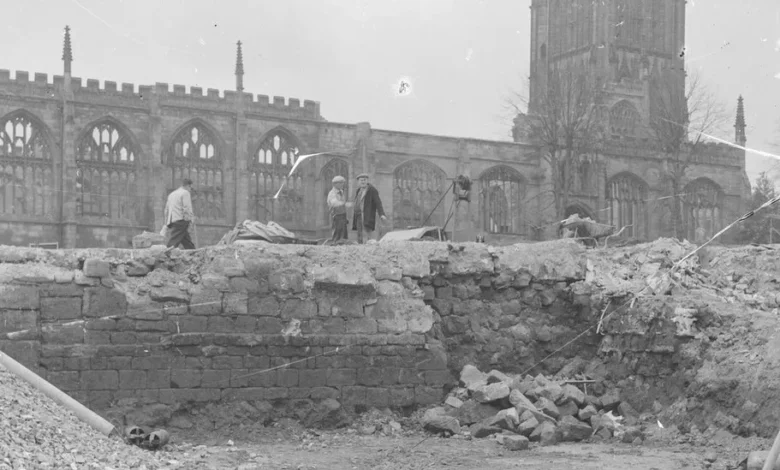

About 800 more negatives, handed to a city archive by a cameraman who saved them from being dumped, also show early excavations for the building of Coventry’s modern cathedral.

They have added to a collection of over 8,000 images taken by Arthur Cooper from the 1930s to the 1960s, and made available to the public as part of the Coventry Digital project.

After the photographer’s death his glass plate negatives, destined for the tip, were rescued by Ian Hollands before the majority were sent to publishing company Mirrorpix.

As well as the city streets, weddings, parades and visiting celebrities are among the collection from the photographer who captured everyday life in the city.

The new collection contained “significant” images that would “greatly enhance” Coventry Cathedral’s archive, said Martin Williams.

The chairman of the Friends of Coventry Cathedral has helped digitize the latest collection as well as identify people and events depicted.

“It’s been quite exciting working through them but some of them were really badly damaged, which is a shame because they are moments in history that have gone,” he said.

Some of the latest collection shows parts of the city’s cathedral and priory site, St Mary’s, dating back to the time of Leofric, the Earl of Mercia and Lady Godiva.

The walls were uncovered during construction of the new cathedral in the mid-1950s.

The photographs “show the scale of the priory complex,” destroyed following the dissolution of the monasteries, said Mr Williams.

City archaeologist at the time, John Shelton, can be seen pictured at the site, he explained.

“He tried to preserve the history of the city before we did archaeology in a big official way, before it became as important as we regard it today,” he added.

There was little organisation in the city at the time “that could bring pressure to bear to make sure our archaeological sites were properly examined,” added Dr Ben Kyneswood, director of the Coventry University initiative.

“What I like about these photographs is they give you a real sense that there is archaeology there, going back a thousand years, nearly, and I’d never seen that before.”

“If it were today there would have been some significant research involved,” he added.

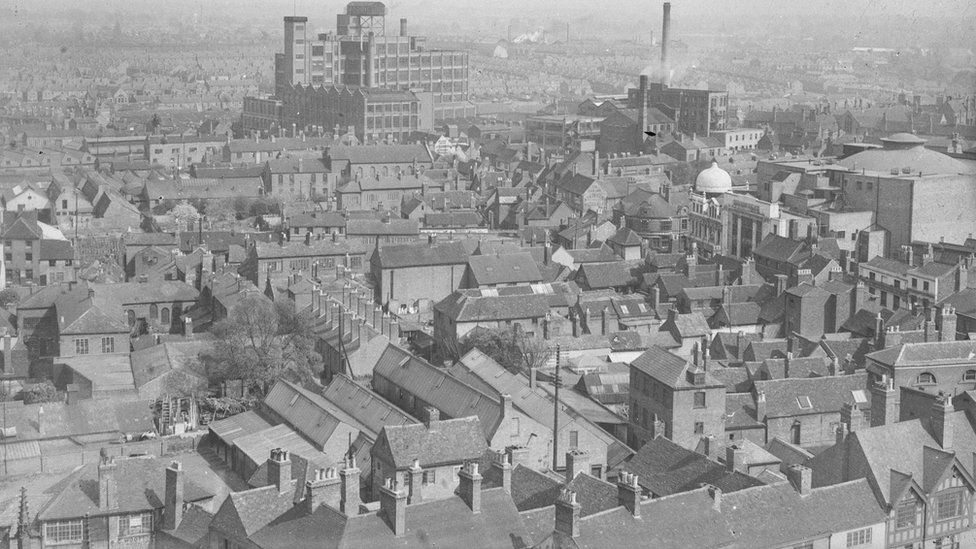

Other pictures show hundreds of concrete piles being driven to form the cathedral’s foundations, and pre-war streets already being cleared under plans to modernise the city, before German bombing accelerated the process.

A mid-1930s view of the city centre shows how planners had “completely changed the road system,” added Dr Kyneswood.

“This whole area was a very narrow medieval street pattern that was all cleared to make way for this brand new Trinity Street which allowed the traffic – increasingly larger vehicles and buses – to travel through through the city centre.”

“Unfortunately, Coventry had a council at the time that was only looking in one direction,” he added, leading to the “tragic” destruction of many mediaeval buildings.

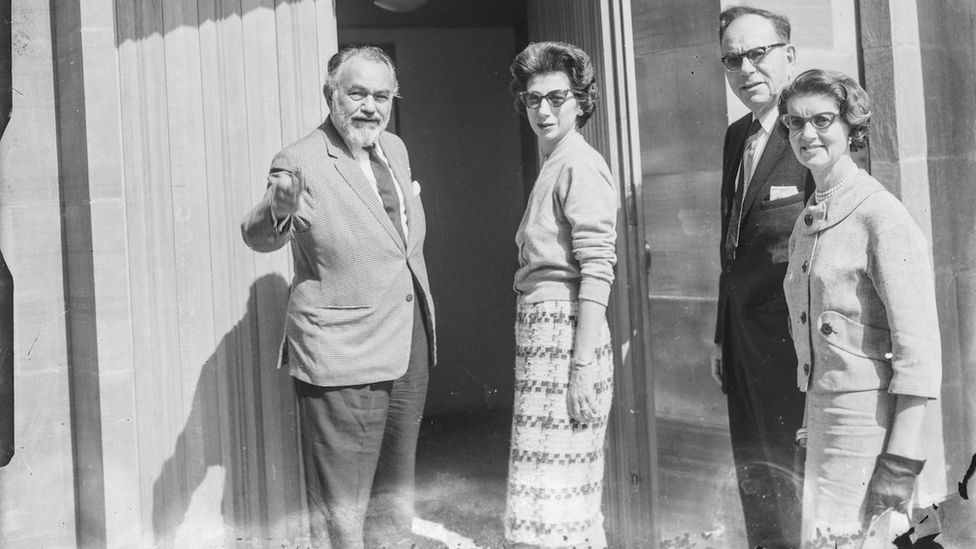

Another picture shows a visit to the city by actor Edward G Robinson, who had been identified by members of the Friends of Coventry Cathedral, said Mr Williams.

“My guess is that he visited Coventry in the summer of 1962 and contrary to the gangster image that he portrayed in many of his roles, he was in person a gentle man with a serious interest in art.”

An image of Pearl Hyde, the first female Lord Mayor of the city, pictured with a Russian icon, was another favourite, he said.

“[The icon] arrived in a parcel with no information so she took it over to the cathedral because she thought it was perhaps a place that should have it,” he explained.

“And then about six weeks later a letter arrived saying it was a gift from Kazan Cathedral in Stalingrad.”

Dr Kyneswood said he would again be working with volunteers around the city to crowdsource information about the photographs.

“The pictures are brilliant, but the main thing is people like Martin and the Historic Coventry Forum and other groups have logged in and said ‘this is what you’re looking at,’ and they’ve told the story, and it’s their version of history.

“And suddenly we get a biography of the photo, which is way more than you would ordinarily get if you go on any website,” he said.

The work with Mirrorpix and owner Reach PLC on the Arthur Cooper collection was “really important, because it is telling that kind of street-level working class stories,” he added.