The photos that chronicle the cost of dying

The cost of dying for those already facing financial pressure is the subject of a new photo exhibition.

Terminally-ill patients allowed award-winning photographer Margaret Mitchell to chronicle their final weeks alive.

The subjects and their loved ones also recorded their struggles as they navigated money worries and illness.

The free exhibition, which has just opened at the University of Glasgow, is the culmination of a four-year study into end-of-life financial pressures.

The aim was to allow participants to tell their own story in words and images.

Stacey: Struggling with taxi fares for appointments

Stacey, 39, lived with a rare hereditary genetic condition called Li-Fraumeni syndrome, which makes a person susceptible to developing cancer. She lived with her partner and her mother in a one-bedroom high-rise flat in Glasgow.

Taxi fares for medical treatment were a burden. “I’m in the health centre for blood Monday, that’s £20. Then to get injections Tuesday – £25. Then to see my surgeon on Thursday at the hospital – £20,” she described.

Stacey’s partner Joost took unpaid leave from his job to care for Stacey and said they struggled financially.

He told BBC Scotland: “In the last month at home, it was three people in one house and that was crowded.

“Stacey’s mum had to sleep in the living room on a couch and we had the bed.”

Stacey died recently.

Liz: Living alone in a leaky flat

A love for fashion and dress-making allowed Liz to create a haven where she felt comfortable.

She knew her own flat was not perfect. Her photographs document the black mould in her bedroom and a leaky ceiling. She knew people might see it as “cluttered” but it was home to her.

Following a diagnosis of terminal lung cancer, Liz struggled to get support. She was estranged from her family and lived alone. She had a partner but they did not live together as she faced her own health issues.

She visited charity, vintage clothes shops and the Mitchell library, partly for warmth but also for conversation.

Her religious faith also provided solace. “I’ve survived with using the radio. When I can’t get to church, I listen to this,” she explained in handwritten notes.

In her final days, faced with reductions in her care package due to staff shortages, she accepted a hospice bed.

Max: An army veteran who wanted to be with his dog

For army veteran Max, remaining at home for the end of his life was a priority. He had experienced homelessness and struggled with institutions. He wanted to be in his local community with friends and his dog, Lily.

“I prefer being at home. No one wants to be in a hospital. I want to do my own thing,” he said.

His home was unfit for his needs, with four sets of stairs and a bath he could not climb into. He was moved into a hospice by concerned carers but before long Max made “a great escape”, according to his friends.

“He did a runner from the hospice basically to get back to his dog,” they recalled.

With their help and support from his care team, Max was able to stay at home with Lily until the last week of his life.

Margaret: Thinking about her daughter’s future

Having grown up in the city, 64-year-old Margaret attributed her cancer diagnosis to pollution. She had lived on a busy road and worked above a bus station for years.

She said: “We went to school in the peasouper. You were all holding onto each other, it was so thick. You couldn’t see anything”.

Margaret left home aged 16 and worked throughout her life. Following her diagnosis, her main concern was making sure her teenage daughter was financially taken care of when she was gone.

With the help of a hospice social worker, Margaret tried to check which benefits she would be eligible for. She was upset when she discovered she would not be able to access her pension.

“I’ve never claimed unemployment benefits, ever. Talking about national insurance stamps, I’m fully booked up. I’m going to lose my old-age pension which I never, ever received”.

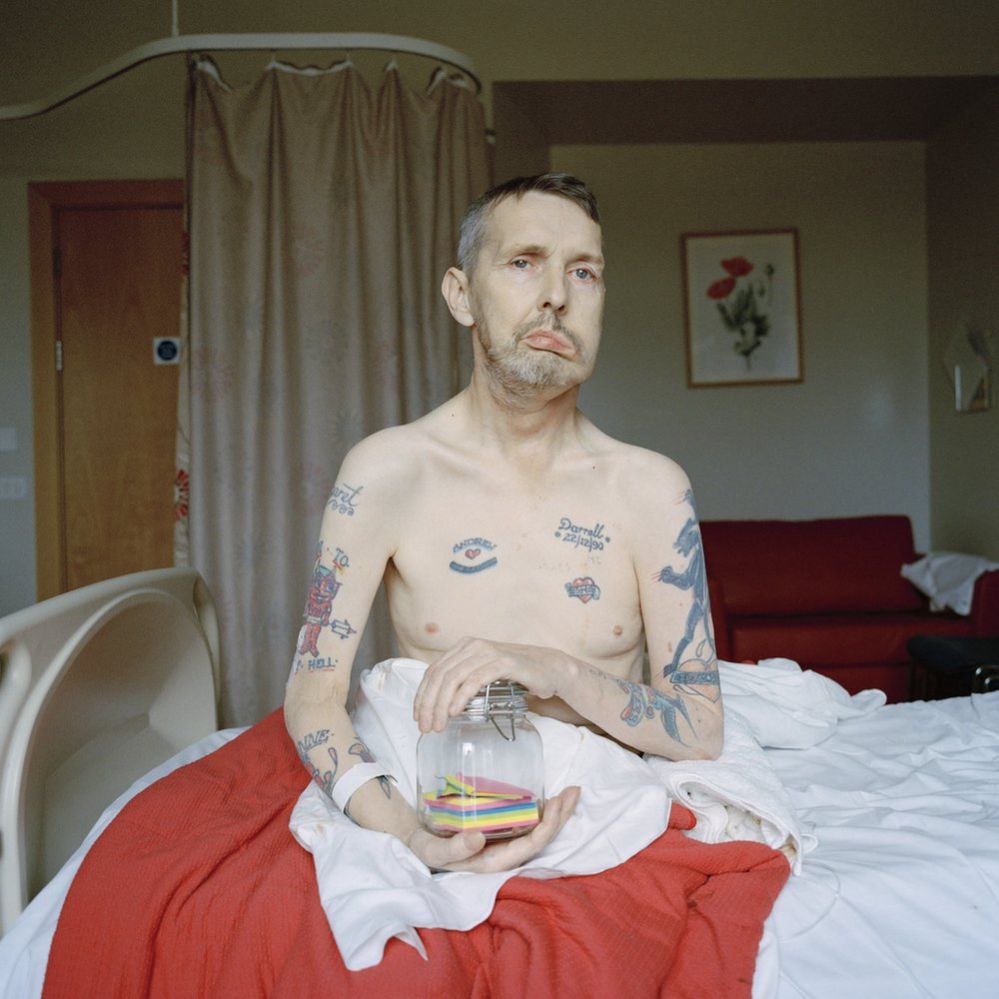

Andy: Leaving notes for his granddaughter

When 53-year-old Andy arrived at the hospice, he was concerned about naming his estranged family in his admission forms in case they were left burdened with his funeral costs.

His diagnosis of throat cancer made it hard for him to communicate. He was very sick and “simply wanted to die”.

Hospice staff were able to help Andy reunite with his family – his daughter and a granddaughter he never knew he had.

The photos that Andy contributed to the exhibition show bags of food his daughter brought him in the hospice.

Photographer Margaret Mitchell noticed a jar with sticky notes by his bedside. Andy explained that he was writing notes to leave to his granddaughter when he was gone.

The Cost of Dying exhibition is the culmination of a four-year University of Glasgow study supported by Marie Curie, called Dying in the Margins.

Through their Glasgow hospice, Marie Curie recruited participants to share their stories in the exhibition.

The charity’s head of research and innovation Dr Emma Carduff said: “Financial hardship should never be a barrier to accessing compassionate end of life care and a dignified end of life experience.

“The majority of stories and images included in this exhibition feature people supported by Marie Curie and highlight the systemic issues faced by those who live in poverty.

“This exhibition, which is the first of its kind, aims to bring these issues to the fore, challenge assumptions and promote action.”

By 2040, it is estimated that up to 10,000 more people than now, will be dying with end-of-life support needs in Scotland.

Researcher Dr Naomi Richards said: “We worked very intimately and closely with our research participants to try to get a sense of their lives – things that give them meaning and the struggles they are having because they are experiencing financial hardship and deprivation.”

Participants told of struggles with income as they were unable to work. Common themes were costs of travel for medical care, utility bills as they spent more time at home and worries about funeral costs.

“The participants were all given cameras and were asked to document through photographs the things that were important to them and the struggles they were having,” she said.

Professional photographer Margaret Mitchell was also asked to create a body of work reflecting their stories and emotions.

“It was a really challenging project but at the same time that’s really rewarding because you feel like you’re going to perhaps make a form of legacy for them,” she said.

“When people come along to see it, hopefully it’s a way of entering peoples lives and trying to understand the situations that they’re in at this time and also some of the issues that are being raised by that.”