Nigeria’s elections have bigger problems than vote trading

Ayisha Osori

When veteran politician Ayo Fayose contested — and won — the June 2014 gubernatorial elections in the southwestern Nigeria state of Ekiti, he mocked Kayode Fayemi, the incumbent who had lost. “People don’t want road infrastructure; they want stomach infrastructure,” Fayose said.

Overnight, he introduced a new lexicon for a decades-old practice and triggered an outsized focus on the sale of votes, or vote trading, as a critical challenge to election integrity in Nigeria.

Indeed, elections in the country have repeatedly been marred by allegations of votes being bought and sold. If the rate was allegedly between $8 and $13 a vote when Fayemi came back to power in 2018 in Ekiti, the stakes are even higher nationally.

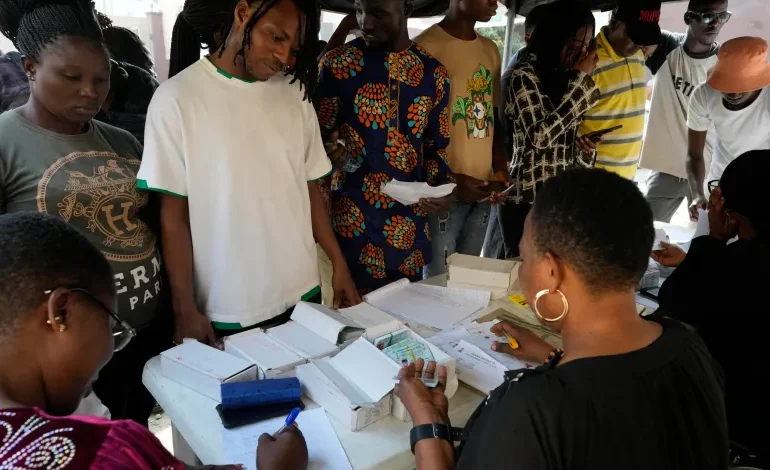

As Nigerians prepare for one of the country’s most decisive and divisive elections since 1999 to pick their president, vice president and members of parliament on February 25, many believe that vote trading will play a determining role.

After all, the primaries of the two main parties, the governing All Progressives Congress and the main opposition Peoples Democratic Party, were particularly contentious in 2022, with allegations of delegates receiving as much as $25,000 each to vote in favour of those paying them.

Yet the focus on vote trading obfuscates far deeper problems with Nigeria’s electoral democracy, and risks covering up for those flaws.

To be sure, vote buying is a major threat to Nigeria, one that is not new. In fact, it is part of Nigeria’s history of transactional politics and elections, where votes are exchanged for food, favour and cash. Before “stomach infrastructure” there was “democracy of the stomach” coined by Ozumba Mbadiwe, a federal minister in the years just before and after independence from the United Kingdom.

The problem is also not unique to Nigeria: At least 165 countries have laws against vote trading. Like Nigeria, votes are influenced by payments or allurements in many other developing world democracies.

Tackling this menace isn’t easy. When the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) announced in October 2022 a move towards a cashless economy and declared that current notes would be no longer valid in the days leading up to the presidential election, many concluded that the move, in part, was targeted at politicians and their cash stockpiles used for vote-buying. Yet days later, the central bank governor Godwin Efemiele found himself in the crosshairs of allegations from the government that he was involved in financing terrorism, charges that many independent analysts do not buy.

Whatever the merits of the allegations against Efemiele, the large question remains: Are Nigeria’s electoral problems fundamentally about vote buying?

Today there are 133 million Nigerians in multidimensional poverty; living on or below the national poverty line of 376.50 naira ($0.51) in earnings a day.

When votes fetch several times that amount, voters are not illogical to sell. They have delayed gratification, between one election cycle and the next, and are not swayed by narratives of future accountable governance and public goods they have never known. Money, food and jobs are concrete and complete the calculation, hardwired into Nigeria’s political culture, that the bird in hand is the only bird. Nigeria’s political economy is extractive and transactional – and financial imperatives are built into every process from the emergence of party candidates to securing judgments at election tribunals.

The Independent Corrupt Practices Commission, an autonomous agency set up by the government in 2000, estimated that 9.4 billion naira ($26 million) were exchanged in bribes for favourable judgements in election-related cases between 2018 and 2020 alone. Voters know this murky reality and expect their cut at the polling unit.

This explains why vote trading prevails despite the increasing sophistication of scripted ‘”do-not-sell-your-vote” messages in pidgin and other languages, and a formal ban against the practice. And if Nigeria’s corrupt electoral system is to be truly reformed, the attention that vote-buying draws must be put in context.

No politician can pay off 50 percent of Nigeria’s 93 million registered voters. Vote-buying strategies work when there are fewer people to pay and when politicians can confirm, or convince voters that they can confirm, whom they actually voted for.

This requires at least three things: low voter turnout arranged through pre-election and election day violence; amplified narratives about the power of vote trading in determining elections to dissuade “unsold” voters from bothering about going to the ballot box; and politicians’ access to voters’ ballots.