World breaches key 1.5C warming mark for record number of days

The world is breaching a key warming threshold at a rate that has scientists concerned.

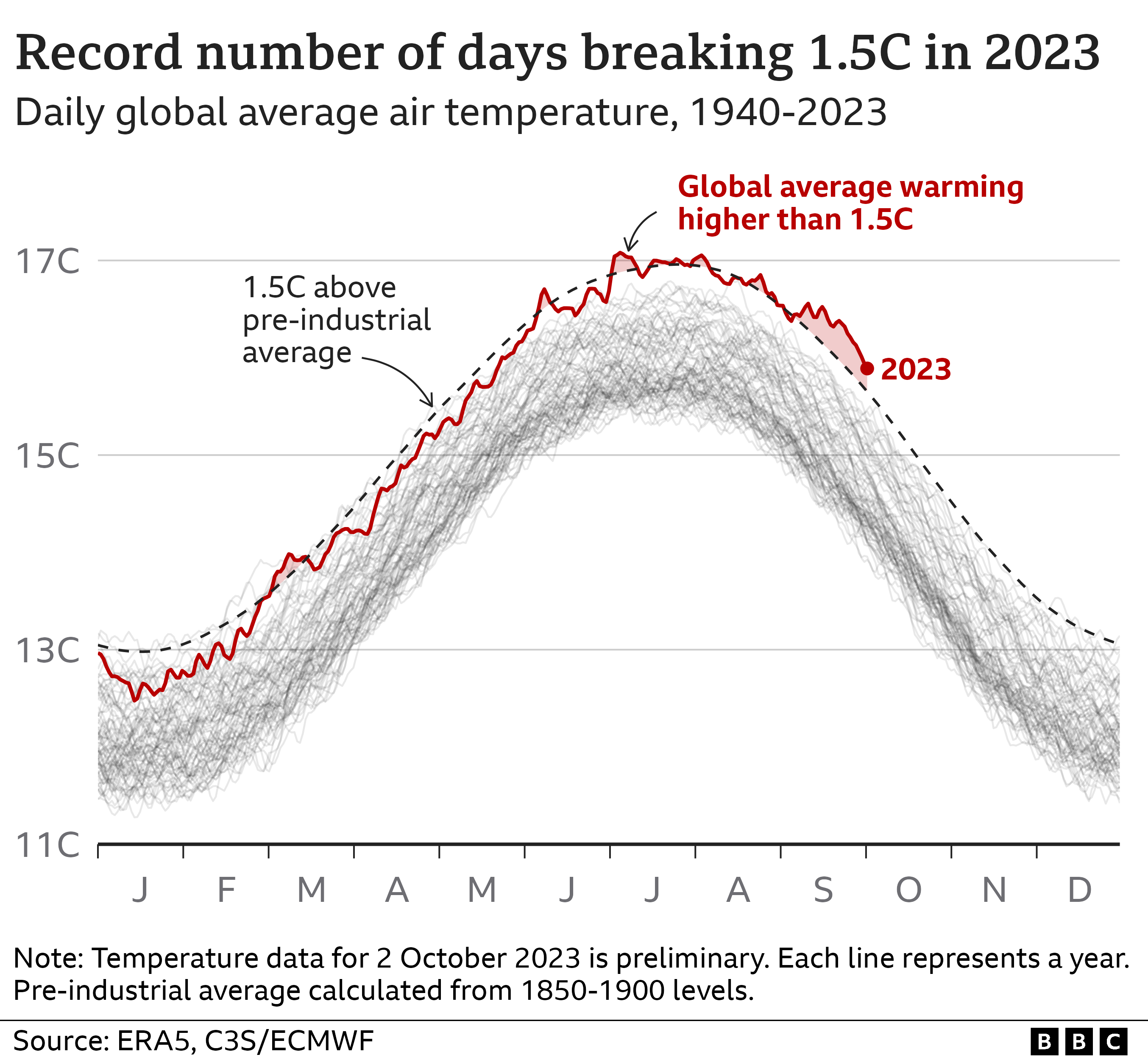

On about a third of days in 2023, the average global temperature was at least 1.5C higher than pre-industrial levels.

Staying below that marker long-term is widely considered crucial to avoid the most damaging impacts of climate change.

But 2023 is “on track” to be the hottest year on record, and 2024 could be hotter.

“It is a sign that we’re reaching levels we haven’t been before,” says Dr Melissa Lazenby, from the University of Sussex.

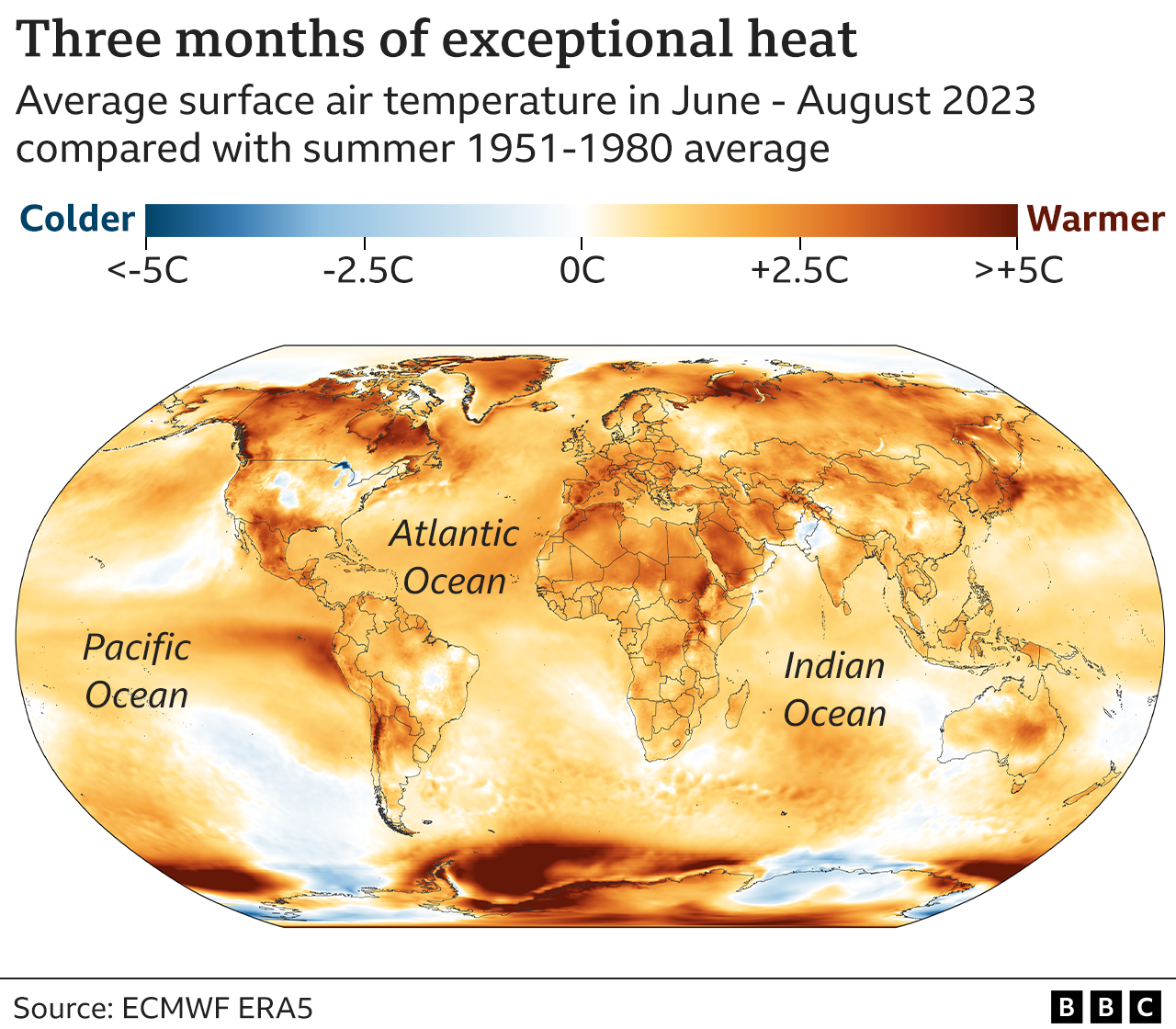

This latest finding comes after record September temperatures and a summer of extreme weather events across much of the world.

When political leaders gathered in Paris in December 2015, they signed an agreement to keep the long-term rise in global temperatures this century “well below” 2C and to make every effort to keep it under 1.5C.

The agreed limits refer to the difference between global average temperatures now and what they were in the pre-industrial period, between 1850 and 1900 – before the widespread use of fossil fuels.

Breaching these Paris thresholds doesn’t mean going over them for a day or a week but instead involves going beyond this limit across a 20 or 30-year average.

This long-term average warming figure currently sits at around 1.1C to 1.2C.

But the more often 1.5C is breached for individual days, the closer the world gets to breaching this mark in the longer term.

The first time this happened in the modern era was for a few days in December 2015, when politicians were signing the deal on the 1.5C threshold.

Since then the limit has been repeatedly broken, typically only for short periods.

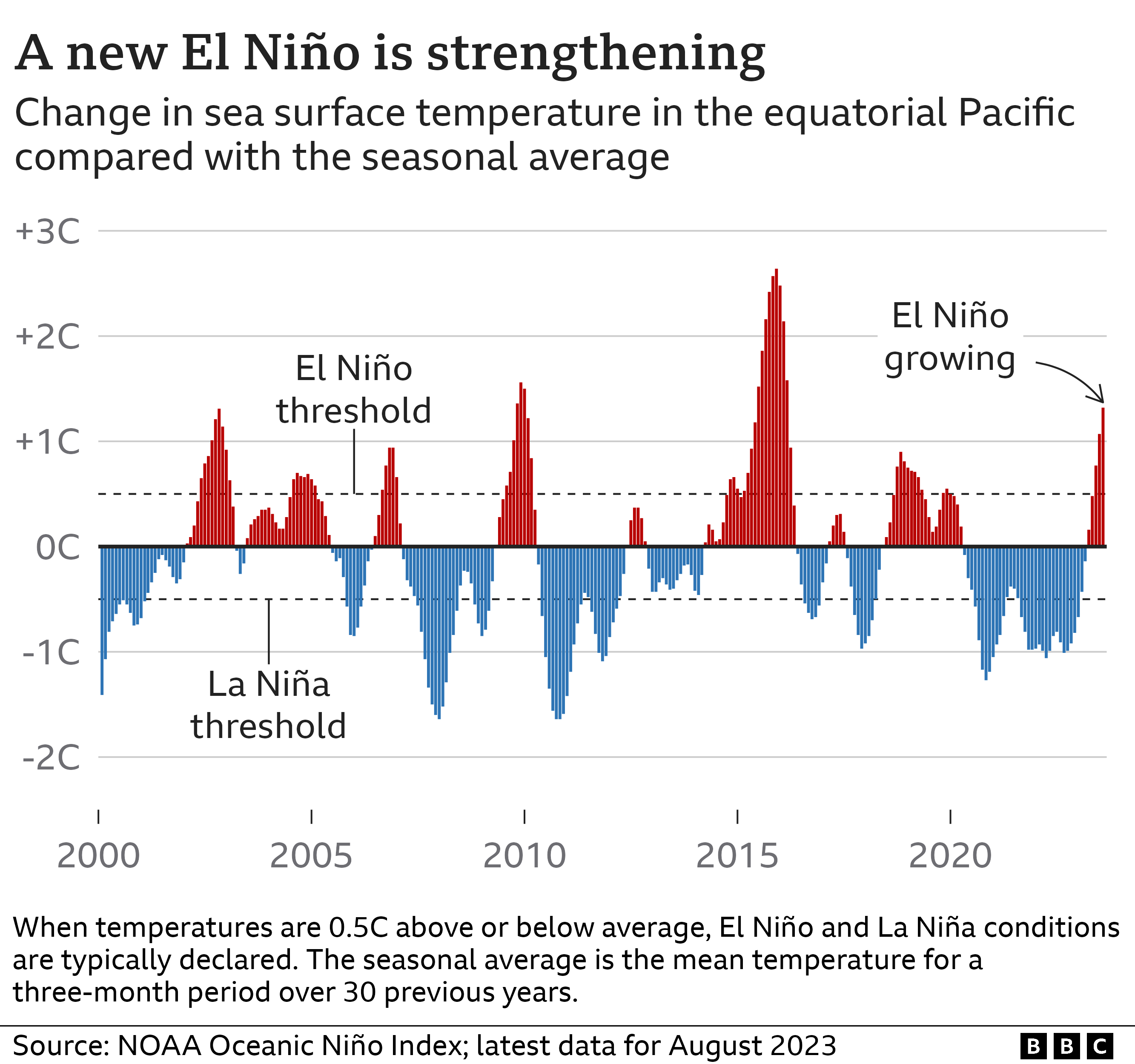

In 2016, influenced by a strong El Niño event – a natural climate shift that tends to increase global temperatures – the world saw around 75 days that went above that mark.

But BBC analysis of data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service shows that, up to 2 October, around 86 days in 2023 have been over 1.5C warmer than the pre-industrial average. That beats the 2016 record well before the end of the year.

There is some uncertainty in the exact number of days that have breached the 1.5C threshold, because the numbers reflect a global average which can come with small data discrepancies. But the margin by which 2023 has already passed 2016 figures gives confidence the record has already been broken.

“The fact that we are reaching this 1.5C anomaly daily, and for a longer number of days, is concerning,” said Dr Lazenby.

One important factor in driving up these temperature anomalies is the onset of El Niño conditions. This was confirmed just a few months ago – although it is still weaker than its 2016 peak.

These conditions are helping to pump heat from the eastern Pacific Ocean into the atmosphere. This may explain why 2023 is the first year in which the 1.5C anomaly has been recorded between June and October – when combined with the long-term warming from burning fossil fuels.

“This is the first time we’re seeing this in the northern hemisphere summer, which is unusual, it’s pretty shocking to see what’s been going on,” said Prof Ed Hawkins, from the University of Reading.

“I know our Australian colleagues are particularly worried about what’s going to be the consequences for them with their summer approaching [for instance extreme wildfires], especially with El Niño.”

Days when the temperature difference has exceeded 1.5C continued into September, with some more than 1.8C above the pre-industrial average.

The month as a whole was 1.75C above the pre-industrial level, and the year to date is around 1.4C above the 1850-1900 average, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

While 2023 is “on track” to become the warmest year on record, it is not expected to breach the 1.5C warming threshold as a global average across the full 12 months.

Contributing factors

The world’s oceans have also been experiencing unusually high temperatures this year and in turn, releasing further heat into the atmosphere.

“The North Atlantic Ocean is the warmest we’ve ever recorded, and if you look at the North Pacific Ocean, there’s a tongue of anomalously warm water stretching all the way from Japan to California,” said Dr Jennifer Francis from the Woodwell Climate Research Centre in the US.

While greenhouse gas emissions are increasing average temperatures, the precise reasons for why these sea temperatures have surged is not fully known.

One theory – which is still uncertain – is that a fall in air pollution from shipping across the North Atlantic has reduced the number of small particles and increased warming.

Up until now, these “aerosols” had been partly offsetting the effect of greenhouse gas emissions by reflecting some of the sun’s energy and keeping the Earth’s surface cooler than it would have been otherwise.

Another perhaps less well-known factor is the situation around Antarctica.

There have been ongoing concerns about the state of sea ice around the coldest continent, with data showing the levels far below any previous winter.

But according to some experts, two spikes in temperature in recent months in Antarctica – triggered by natural variability – have boosted the global average. However, it’s difficult to identify the precise influence of long-term human-caused warming.

“In early July, Antarctica got really warm, they saw record temperatures, which is still 20 or 30 degrees Celsius below zero,” said Dr Karsten Haustein, from the University of Leipzig.

“And what we see with 1.5C and 1.8C anomalies we are seeing now, it is partially down to Antarctica again.”

While the northern hemisphere will naturally cool in autumn and winter, there is a view that the large temperature differences from the pre-industrial period may persist, especially as El Niño reaches a peak at the end of this year or early next.

Researchers believe that these ongoing high temperature anomalies should be a wake-up call for political leaders, who will gather in Dubai in November for the COP28 climate summit.

Action on emissions is needed, they say, and not just in the long-term.

In March, the UN urged countries to accelerate climate action, stressing effective options to reduce emissions were available now, from renewables to electric vehicles.

“It’s not just about reaching an end goal, of net zero by 2050, it’s about how we get there,” said Prof Hawkins.

“The IPCC [the UN’s climate body] very clearly says we need to halve emissions over this decade, and then get to net zero. It’s not just about reaching net zero at some point, it’s about the pathway to get there.”

And as this year’s extreme weather events have shown – from heatwaves in Europe to extreme rainfall in Libya – the consequences of climate change increase with every fraction of a degree of warming.