Why have there been no named winter storms this year?

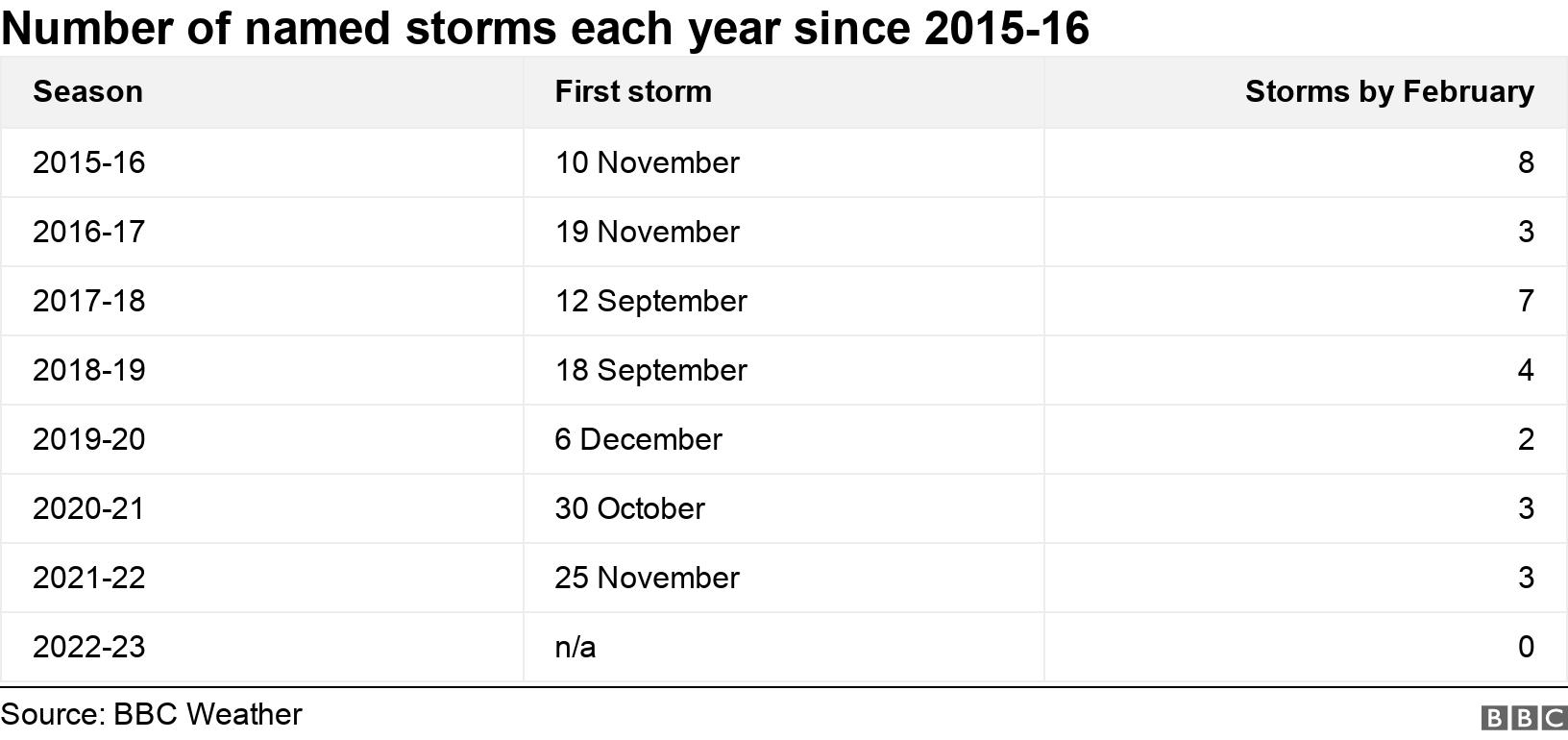

By February, the UK would normally have had around three storms given names by the Met Office – just like Arwen, Barra and Callum. But so far this autumn and winter, there hasn’t been a single one.

Weather patterns have been calmer across the Atlantic and towards northwest Europe. But why?

There are a number of factors at play – and the forces behind this year’s lack of storms were also instrumental in December’s cold snap.

In previous years, the first named storm has taken place by early December. And by the end of January, typically three storms would have formed, bringing impacts to the UK.

Storms can bring a danger to life and cause millions of pounds worth of damage from strong winds, heavy rain and even significant snowfall.

The busiest autumn/winter season was 2015-16, when a total of eight named storms had hit the UK by the start of February.

During February 2022, three storms were named within a week. Dudley, Eunice and Franklin impacted hundreds of thousands of homes.

The insurance payouts resulting from the three storms was close to £500 million, according to the Association of British Insurers.

Storm Eunice was one of the worst storms to hit the UK in 30 years, with rare red warnings issued across south Wales and southern England.

Eunice was also responsible for a new England wind gust record of 122mph at The Needles on the Isle of Wight.

Windstorms in the UK are usually caused by little wobbles in an active jet stream (a corridor of strong winds around 30-40,000ft up in our atmosphere) over the Atlantic directed towards northwest Europe.

In some circumstances, the atmospheric conditions can create explosive cyclogenesis – or a weather bomb – just to the west of the UK, which can bring the most damaging winds.

Naming storms was started by the Met Office and Ireland’s Met Eireann in 2015, with the idea of being able to communicate the hazards and warnings associated with them.

The Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) joined the initiative in 2019 so also contributes names to the list.

Why so quiet this season?

Last year, our autumn – which, meteorologically speaking, runs from September to November – was the third warmest on record.

While rainfall increased after the very dry spring and summer, it was only marginally above average.

Into the start of winter, December was the first month in 18 where the average temperature went below average.

December’s cold snap was due in part to what is known as a “blocking weather pattern”. At the time, this pattern was over Western Europe, and preventing weather systems from reaching the UK.

The UK’s lack of named storms this season is likely to be due to the position of the Polar jet stream, a ribbon of strong winds high in the atmosphere that create and drive weather systems across the Atlantic to northwest Europe.

Other parts of Europe have had more than their usual share of named storms. There have been eight in the southwest Europe naming group, which includes France, Spain, Portugal and Belgium.

The UK’s cold snap may be partially due to the fact that a naturally occurring climate pattern called La Nina – which means large-scale cooling in the Pacific – is in its third consecutive year. This is known as a “triple-dip”.

In this phase, UK winters tend to be colder and calmer at the start then switch to milder, wetter and windier weather toward the end of the season.

Experts believe that rising global temperatures mean that La Nina and El Nino – the opposite of La Nina – events will become stronger by 2030.

What about the rest of winter?

The current forecast suggests high pressure will keep things relatively settled for most of the UK for the first week of February.

Any spells of wet and windy weather will be limited to northern areas of the UK.

Weather forecasts beyond a week ahead are generally uncertain but, into the middle of February, there are signs it could turn wetter and windier more widely.

How does climate change affect windstorms?

According to the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), the link between climate change and extra-tropical cyclones – the storms that normally affect northwest Europe – is currently unclear.

They suggest that European windstorms have actually reduced in frequency over the last few decades.

However, it is widely accepted that when we do get storms, climate change is likely to make them more extreme with higher rainfall totals and potentially greater impacts.