Why boarding schools for toddlers are gaining popularity in Lesotho

It’s a bright, cloudless day in Maseru and within the confines of a small green-and-white-fenced compound, about a dozen children in yellow school uniforms – many of them toddlers – run around.

A middle-aged woman saunters through the school’s gate. All of a sudden, the children stop playing and rush forward, swarming her like a bike of bees. She complains good-naturedly that she is tired but this doesn’t stop her from hugging the little ones. It’s almost like she is their mother.

It’s a bright, cloudless day in Maseru and within the confines of a small green-and-white-fenced compound, about a dozen children in yellow school uniforms – many of them toddlers – run around.

A middle-aged woman saunters through the school’s gate. All of a sudden, the children stop playing and rush forward, swarming her like a bike of bees. She complains good-naturedly that she is tired but this doesn’t stop her from hugging the little ones. It’s almost like she is their mother.Although it is difficult to track the number of boarding schools for toddlers that exist – a request Al Jazeera sent to the Ministry of Education went unanswered – the phenomenon is spreading in Lesotho, according to local media.

“These schools [are] … particularly helping parents eager to seek employment in foreign lands but cannot take their children along,” said an April report published in the Lesotho Times.

“We take in children from an age range of two years to 12 years,” Phalatse told Al Jazeera. CGC’s fees are 2,500 South African rand ($144) a month, which pays for classes, lodging, food and general care.

Lesotho has a 16.5 percent unemployment rate. Although this is lower than its bigger neighbour, a government policy document said that between 2018 and 2023 only 10 percent of Lesotho’s population of 2.3 million was employed in the formal sector and that the country is “among the 10 most unequal countries in the world”.

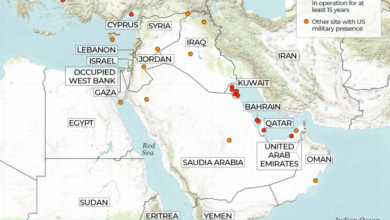

Being entirely surrounded by South Africa, Lesotho’s economy is also largely dependent on its neighbour, through which it receives all imports. It is also one of the most migration-dependent countries in the world, a report prepared for the International Organization for Migration (IOM) noted.

Many people from Lesotho – particularly lower-skilled and informal sector workers, including supermarket cashiers, domestic helpers and factory workers – migrate to South Africa in search of economic opportunities and leave their children behind, NGOs note.

According to Integral Human Development, “43% of the households in Lesotho have at least one of its members living away from home.”

While the IOM says there isn’t much reliable migration data for Lesotho, according to 2022 data from the World Bank, remittances contribute about 23 percent to the country’s GDP.

A ‘safe’ place

“In general, people leave Lesotho and their children to look for better jobs in South Africa,” said Thapelo Khasela, the general manager at Action Lesotho, an anti-poverty NGO that has worked to support orphans and other vulnerable people.

In most cases, the parents who leave are lower-skilled workers who feel there are more opportunities for them in a much larger economy.

“For instance, the same factory worker who earns 2,500 rand ($144) in Lesotho can earn a minimum of 4,000 rand ($231) in South African factories using a piece rate system … It is relatively easy for unskilled labour to get employed in South Africa than it is in Lesotho,” he told Al Jazeera.

Lesotho’s mandated minimum monthly wage is between $120 and $130, which puts boarding schools like CGC out of reach for many. But for parents living in neighbouring countries who can earn a bit of a higher salary, the schools are a better option than leaving their children with nannies or relatives.