What lies ahead for the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh?

After Azerbaijan’s lightning military offensive, the future of the 120,000 ethnic Armenians who dominate the Nagorno-Karabakh region hangs in the balance.

The latest clash of a decades-old conflict broke out on Tuesday, but ended a day later with Armenian separatists agreeing to lay down their arms.Azeri President Ilham Aliyev declared victory over the enclave on Thursday, saying it was fully under Baku’s control and that the idea of an independent Nagorno-Karabakh was finally confined to history.

He promised to guarantee the rights and security of Armenians living in the region, but years of hate speech and violence between the rivals have left deep scars.

Thousands of ethnic Armenians massed at Stepanakert Airport after the ceasefire was agreed, ostensibly fearing a crackdown.

Many in Nagorno-Karabakh say they have little trust in any reintegration process.

“Integration in this situation means nothing else than captivity,” said Yani Avanesyan, a doctoral researcher at Artsakh State University; Armenians have self-styled Nagorno Karabakh as the Republic of Artsakh.

“I don’t know anybody here, any Armenian in Nagorno-Karabakh that could imagine being integrated and being safe at the same time,” said journalist Siranush Sargsyan, speaking from Stepanakert, the de facto capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, called Khankendi by Azerbaijan.

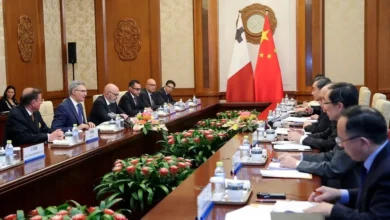

Officials from Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh met on Thursday to discuss security guarantees and humanitarian assistance. But as of Friday, no deal had been reached, besides the entry of a humanitarian convoy into the region.

The humanitarian aid group HART, which has been active in the region for 30 years, warned of a humanitarian catastrophe due to a nine-month blockade, which has stretched supplies.

In December last year, Baku closed off the Lachin Corridor, the only road connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, causing a dire humanitarian crisis.

Residents said they felt alarmed when they heard the separatist forces were surrendering; displaced people were out on the streets clinging onto their bags, while crowds flocked to the airport of Stepanakert, an area controlled by Russian peacekeepers.

Artak Beglaryan, an ex-state minister of the self-styled Artsakh and head of the human rights ombudsman during the 2020 war, called for global support.

“Without international high-level guarantees, it’s impossible [to sign an agreement] given the depth of the conflict,” Beglaryan told Al Jazeera. “People here fear that we are still under high risk of genocide and ethnic cleansing, and that’s why an overwhelming majority is thinking of fleeing the country.”

The Armenian government says it is preparing to accept tens of thousands of people who leave Nagorno-Karabakh if it becomes impossible for them to stay under Azerbaijani rule.

While there has not been agreement yet on security guarantees, Azerbaijan says that the ethnic Armenian fighters who have agreed to disarm will have a choice whether to stay or leave.

“We agreed that [those] who put down their guns and do not use force against Azerbaijani forces, simply they should be set free and they should decide whether they would stay in Karabakh or go to Armenia,” said Hikmet Hajiev, foreign policy adviser to Aliyev. “It is their ultimate decision.”

Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognised as part of Azerbaijan but is predominantly populated by ethnic Armenians who have long sought independence from Baku.

In the early 1990s, Armenian forces gained full control of the enclave and surrounding territories causing an exodus of Azeris.

Figures from the UN Human Rights Office show that Azerbaijan hosted more than 800,000 internally displaced Azeri refugees in 1994. More than 300,000 ethnic Armenians living in Azerbaijan escaped to Armenia.

But the power dynamic in the region shifted in the decades that followed. Resource-rich Azerbaijan used oil and gas proceeds to expand its military capacity while strengthening ties with international powers, especially neighbouring Turkey. On the other side, Armenia found itself increasingly isolated and economically weakened.

So in 2020, when Azerbaijan launched another military operation in Nagorno-Karabakh, it was able to swiftly regain control of districts in and around the enclave and resettle some internally displaced Azeris in the territory.

With that, years of discussion to grant autonomy to Nagorno-Karabakh and special rights to its citizens were thrown out of the window, said Artin Dersimonian, research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft’s Eurasia Program.

“Since then Azerbaijan became much more arrogant, emboldened by its victory and considering Nagorno-Karabakh an internal matter – one in which no one had the right to dictate what rights should be guaranteed and to whom,” said Dersimonian.

“Azerbaijan has been steady in rejecting any conversation on minority rights protection, though this might change with outside pressure. But regardless of that, even if there was a wide range of guarantees, they [Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh] will not trust Baku to enforce them,” he added.

But Esmira Jafarova, board member of the Center of Analysis of International Relations, said Azerbaijan has long sought dialogue that was rejected by the separatist forces.

“Under these conditions now, they have agreed to talk,” said Jafarova, who is also a former Azeri diplomat and adviser to the minister of energy. “The Azerbaijani authorities have put forward plans for their reintegration, for their cultural rights, educational rights and this is all under discussion and I am sure that both sides could find common ground in the coming meetings.”