‘We fled oppression, not our home’: Albania to Australia and back again

Almost every evening during the summer of 1975, Bajram Fezollari’s father, Feridon, would take him on a walk along the banks of Lake Ohrid.

But these were not simply strolls for bonding purposes between a once-distant father who had spent more than a decade behind bars and his teenage son. In reality, the two were on a stealth mission.

On and off for four years, Feridon had been strolling along the Pogradec lakeside, meticulously monitoring how and when the police patrolled the waters and the surrounding area.

He observed how many guards were on duty at any given time, when they would change over, how many lights they would project onto the lake at night, and from what positions.

Then, one night in the summer of 1975, after years of watching and months of planning, the family made their move for freedom from the political persecution they had endured for years.

Feridon, a 16-year-old Bajram and 14 members of their extended family set out in the dead of night, boarded a wooden boat they had built themselves and made a gruelling, eight-hour journey across the lake to what is now North Macedonia in neighbouring Yugoslavia, before eventually travelling to Australia where they claimed political asylum and made a new life.

No exit

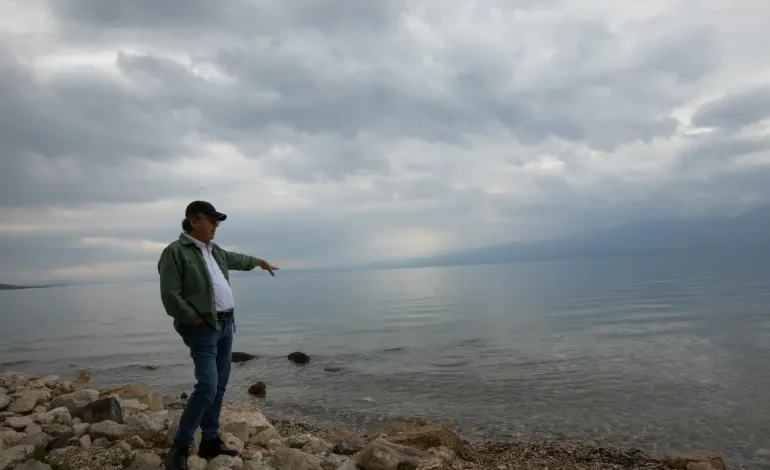

Nearly 50 years since that night, Bajram stands at the bar he now owns on the banks of Lake Ohrid and recalls the journey his family took from this same spot – one that turned into a round-trip decades later when he decided to return.

When the Fezollaris left Albania, the country was in the iron grip of dictator Enver Hoxha, under whom, for more than 40 years, it became one of the most isolated and repressive places in the world.

During the communist regime, which lasted from 1945 to 1991, emigration from Albania was officially prohibited and anyone caught trying to leave the country could be shot or punished with prison terms of anything from 10 to 25 years.According to a recently disclosed November 1990 Ministry of Interior document marked “Top Secret” and signed by the minister at the time, Hekuran Isai: “From 1944–1989, the number of people escaping from Albania were 13,692 people, of whom 988 died.”

Even in 1990, by which time restrictions had been somewhat eased, 54 people were killed at Albanian borders – although the identities of those responsible have never been made clear.

Along border areas like Lake Ohrid, guards would patrol, tasked with not allowing anyone to leave. In some cases, they were even instructed to shoot those caught trying.

“When I think back, our chances of not being detected by the guards or drowning [the night we left] were a mere 5 percent,” Bajram says now, reflecting on how lucky they were to have made it out.

A ‘segmented’ brain drain

Emigration among Albanians is not new. Like the Fezollaris in the 1970s and, later, other families who moved when the country opened up to the world in the 1990s, people have regularly been on the move.

According to data from the Albanian Institute of Statistics and the United Nations, from the fall of communism in 1991 until 2022, more than a third of the population is thought to have left the country. Between 1.2 million to 1.4 million people left Albania in that time, while the population has fallen from 3.3 million in 1991 to 2.8 million overall in 2023.

By 2011, Albanians had gained the right to travel visa-free to the European Schengen area, and in recent years, professionals have been given the right to work in some countries such as Germany.

Today, it is estimated that 42,000 Albanians migrate each year. Young professionals such as doctors and nurses are those who do so the most, creating a void in the country, which is proving difficult to fill.

A report on this issue by the University of Sussex in 2023 concluded, “This loss of doctors represents a massive loss of both human capital and investment in the production of that human capital.”

The longer-term trend of migration for Albanians has persisted despite the fact they have not always been warmly welcomed in other countries. In 2022 and 2023, Albanian migration to the United Kingdom was thrust into the spotlight when the British government raised the alarm about the numbers crossing the perilous English Channel in small boats.

In 2023, the flow of Albanian asylum seekers towards the UK saw a significant decrease, partly because of measures taken by the governments of both countries. But the racism and violence that many endure have persisted.

None of this has stopped Albanian emigration, however. The study by the University of Sussex found that “Most Albanian emigrant doctors do not plan to return to Albania. The obstacles deterring return are more or less the same as those driving emigration. [There is a] general feeling that ‘there is no future in Albania’.”

A few like Bajram, however, have bucked this trend.