‘Very thin budget’: Forex shortage triggers cost-of-living crisis in Malawi

Joe Kambale has been stitching men’s suits from his living room in Blantyre, Malawi’s commercial hub, for the last eight years. Sometimes he makes about 200,000 kwacha ($173) a week, decent wages in a country where half of the population lives on $1 daily or less, according to data from Malawi’s National Statistical Office.

He was often so swamped with work that he was sometimes unable to take on new customers for up to a month. But in the last two weeks, the 35-year-old tailor’s pair of sewing machines have been idle because demand is dwindling.And now he is finding it hard to cater to the needs of his wife and one-year-old son.

“The high cost of living has driven clients away,” he said, with a look of despair in his eyes. A month ago, two of his most loyal customers suspended orders indefinitely, telling him that they are now prioritising spending their earnings on basic needs.

The rising cost of materials is also eating into the small profit margins for Kambale’s business, which is run on a shoestring budget.

“Most of the materials that we use in tailoring are imported. When I go to the market to buy them, I find prices have increased because of dwindling imports. Almost every day prices are changing,” said Kambale. “Raising the prices of my suits is difficult because I might lose customers. I’m making losses.”

Life in this southern African country of 20 million people has become harder in recent years.

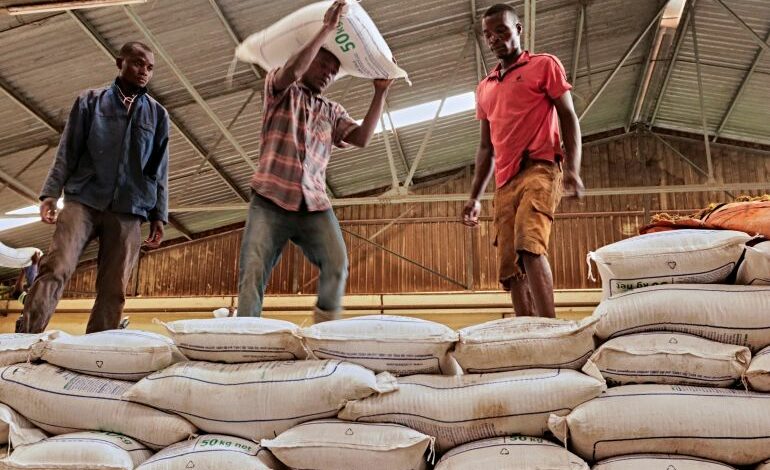

Since 2021, the country has been experiencing acute foreign currency shortages, a consequence of reduced exports, experts say. This has led to a scarcity of essential goods such as food, medicine, fertiliser and fuel. In June, spokesperson for the Reserve Bank of Malawi, Ralph Tseka, told local media that the foreign exchange reserves were “nearly empty”.

Analysts like Betchani Tchereni, associate professor of economics and dean at the Malawi University of Business and Applied Sciences say Malawi is still feeling the effects of COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine on the global supply chain. Since the conflict began in February 2022, the price of bread has increased by at least 50 percent.

“The pandemic destabilised tobacco export and when the war started, the prices of chemical fertiliser skyrocketed, meaning that we couldn’t afford the quantities that we needed any more,” he said. “This also came at a time global inflation in general went up meaning that we couldn’t afford many imports. It further drained our forex and led to inflation.”

‘The worst is yet to come’

To stabilise dwindling forex reserves, Malawi’s central bank devalued the kwacha by 25 percent last May. As of this October, the currency had further weakened by 4.87 percent. Due to rocketing year-on-year inflation – 28.6 percent as of September – everything from food to electricity has gone above the reach of most people.

For instance, Malawi’s main staple, maize, has increased by 15 percent, according to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network. As of June, a family of six in an urban setting needed 377,892 kwacha ($326.53) per month to survive, up from 257,028 kwacha ($222.09) during a similar period last year, according to the Centre for Social Concern-CfCS, a local research-based non-profit.

“The worst is yet to come,” John Kapito, executive director of the Consumers Association of Malawi, told Al Jazeera. “For a long time, the country has failed to balance its imports against exports and has relied heavily on donors for its forex reserves. Our government is in no position where it can cushion anyone. Its revenue collection has drastically gone down as a result of market inactivity and [it] is currently struggling to pay its oversize civil service.”

Agriculture predominantly powers Malawi’s economy, contributing approximately a third of its gross domestic product. Yet, even annual revenue from tobacco, the country’s major foreign exchange earner with $283m in sales already this year, is insufficient to cover the country’s imports bill. According to the Reserve Bank of Malawi, the country requires $3bn annually to meet import requirements but only earns about $1bn.

“For a predominantly exporting country like ours we want the exchange rate to be as strong as possible because that makes the goods affordable but that works if forex is available and obviously that’s not the case with us,” said Tchereni. “It means that every time we are devaluing the kwacha against the US dollar and other currencies, commodities become expensive, disproportionately affecting the ultra-poor people, as is the current situation.”

With the country’s economy in bad shape, the need to move towards greater economic stability has become increasingly urgent. Tchereni believes the private sector is the engine to drive that development. “It is the role of the private sector to generate forex and engage in import substitution. Regrettably, as a country, we’ve fallen short in this area,” he told Al Jazeera.