US education: The endless burden of deliberate ignorance

Donald Earl Collins

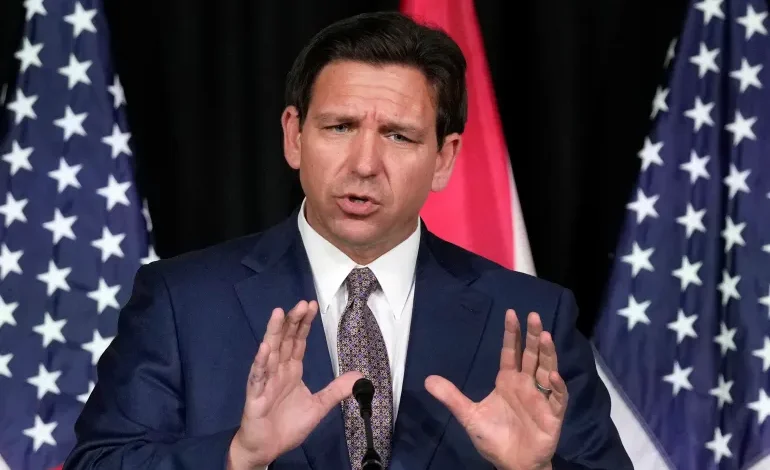

This January, Florida’s Republican Governor Ron DeSantis blocked a proposed Advanced Placement (AP) African American studies course in his state claiming that it had “a political agenda” and included a study of “Queer Theory” and mentions of “Critical Race Theory”. A few weeks later, he threatened to ban the entire AP programme, which offers undergraduate university-level curricula and examinations to high school students.

The governor’s move to block the proposed AP African American studies course and his wider attacks on the programme that helps prepare young people for college was a predictable effort to increase his popularity with Donald Trump’s base and his chances of securing the Republican presidential nomination. It was also in line with other Republican leaders’ interventions in curriculum and book bans elsewhere in the country aiming to prevent anyone from teaching anything dealing with race, sexual orientation and gender identity to American youths.These attacks on so-called “woke education” will have innumerable consequences. The biggest one, perhaps, is one that has gone mostly undiscussed.

If K-12 students are forbidden to learn about the history of racism and anti-racism in the US, about the existence and the struggles of Black folk and queer folx, then when would they learn all this? An undergraduate course on US or African American history would then become the first time millions of these students will learn about the good, the bad and the ugly in these histories. That is, of course, if they ever attend college at all. And those who encounter these subjects in an educational setting for the first time in university inevitably show some resistance. They try to hold on to stereotypes about Black people, queer people and all the other marginalised groups in the US that they picked up from media and society at large, turning education into a battle for lecturers attempting to teach them the truth about the US and the world.

This battle, sadly, has been under way for a very long time.

I have taught more than 100 college-level courses in my academic career, including more than two dozen courses in African American history and African Diaspora studies and I have spent so much of that time dispelling stereotypes about Black Americans and racism. Not just with my white students or with students of colour who aren’t Black. With all of my students. Stereotypes like all Black people are either mired in endless poverty or super wealthy like Oprah or LeBron James. Stereotypes like African Black folk and Asian Americans achieving success in the US because of their belief in individualism and hard work while African Americans lie around waiting for the US government to cut them a welfare cheque. Or even bigger stereotypes, like the only form of racism in the US is as obvious as the Ku Klux Klan in white sheets and white hoods burning crosses or deranged white Americans yelling the n-word.When, as a college professor you are dealing with undergraduates who have heard and taken to heart these and so many other racist stereotypes, and never received any meaningful pushback in K12 classrooms, every lecture, every discussion, and every reading can be like Sisyphus pushing a boulder uphill. Over and over again, I have read writing assignments where students have concluded, “Slavery was a long time ago. We should leave the past in the past and move on.” Or, “America has made so much progress on race relations since the Civil Rights Movement,” as if racism no longer exists.

As an historian and an American Black person, it is infuriating to spend so much time breaking down the legacy of systemic racism and anti-Blackness in the US, in Europe and in the world, only to see so little of what I’ve been teaching reflected in my students’ efforts. And that frustration builds up, semester after semester and year after year. It’s a wonder that I and more of my colleagues don’t end up resigning and leaving college teaching for good.

All of this is a result of a deliberately calibrated ignorance, part of what sociologist Crystal Fleming calls “racial stupidity”. As Fleming wrote in her 2018 book How to be Less Stupid About Race, “one of the main consequences of centuries of racism is that we are all systematically exposed to racial stupidity and racist beliefs that warp our understandings of society, history, and ourselves”.

Deliberate actions to ban curricula and books on race and racism in the US will inevitably continue to leave higher education faculty like me swimming against a tsunami of racist ideas and students who, more often than not, are proud of their ignorance. And it will set Black, Brown, and queer students up for a traumatising educational experience – one where they will face racist and queerphobic slurs and erasure in classrooms, hallways, playgrounds, auditoriums, media rooms and lunchrooms, from age five until adulthood, every day.Yet there is no Ron DeSantis, Moms for Liberty, or Moms for America working to keep marginalised students from experiencing the default deluge of racism, homophobia and transphobia in America’s schools.

Those who are working to end so-called “wokeness” in American schools do not care about the trauma marginalised students will experience as a result of their efforts. They only care that people like them – people who are very white and very heteronormative – continue to control the world unchallenged.

Some universities have moved, rather reluctantly, to try to bridge the gap K-12 education leaves around history, race and racism, and queer and gender studies with a first-year course or two on anti-racism and social identity.

American University and the University of Pittsburgh are just two examples of institutions that have moved to implement such courses. American University began requiring AUx I (American University Experience) and AUx II as first-year core courses in 2018, in the aftermath of a series of racist and anti-Semitic incidents on campus and demands from student groups to do more to protect marginalised students.

The University of Pittsburgh (my undergraduate alma mater) put together its required Anti-Black Racism: History, Ideology, and Resistance course for all first-year students in “response to the 2020 police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade and many others”.

It is still too early to tell if courses like these will work to close the yawning chasm of racist and transphobic ignorance incoming college students hold. As University of Pittsburgh alumna Sydney Massenberg said on the eve of Pitt’s implementation of its anti-racism course, “Racism is definitely not going to be something we eradicate by putting students in a couple of classes. Being an anti-racist requires a lifetime of work on everyone’s part.”

And there are other issues with trying to address this ignorance with a few undergraduate courses. Although it is true every student will have certain degrees of ignorance and blind spots around racism and queerphobia, by the time they reached university, most Black and Brown and queer students would have already experienced these -isms, systemically, institutionally, and interpersonally. “Of course … some people are more afflicted by racial stupidity than others,” Fleming wrote regarding Americans with various layers of privilege, insulating them from confronting their -isms. So these courses may well be setting such students up for more trauma, especially at predominantly white institutions.

This is already the case for faculty teaching such courses. “We had our qualifications challenged, we had a lot of coded racist language thrown at us that amounted to ‘what about the white students?’ They were particularly concerned over conservative white students,” Roshan Abraham, a one-time AUx II adviser and an adjunct professor of religion at American University said.

According to one report, at least a half-dozen advisers in the AUx programme had resigned between 2018 and 2020, due in part to the existing institutional racism and the emphasis on not traumatising white students over their racism and other blind spots.

Whatever the case, the questions remain: Will the politics of intolerance continue to burden the handfuls of professors like me with the task of dispelling never-ending amounts of racism and stereotypes while attempting to teach? Will universities continue to use cover-your-butt one-credit courses as a way to at least alert students to their own ignorance about marginalised groups in the US and the West? And, most crucially, will the US continue to feed this deliberate ignorance and allow students coming out of its schools steeped in dangerous -isms to destroy any hope of a sustainable future for all Americans in this country?