Unseen images of code breaking computer that helped win WW2

GCHQ has released never before seen images of Colossus, the UK’s secret code-breaking computer credited with helping the Allies win World War Two.

The intelligence agency is publishing them to mark the 80th anniversary of the device’s invention.

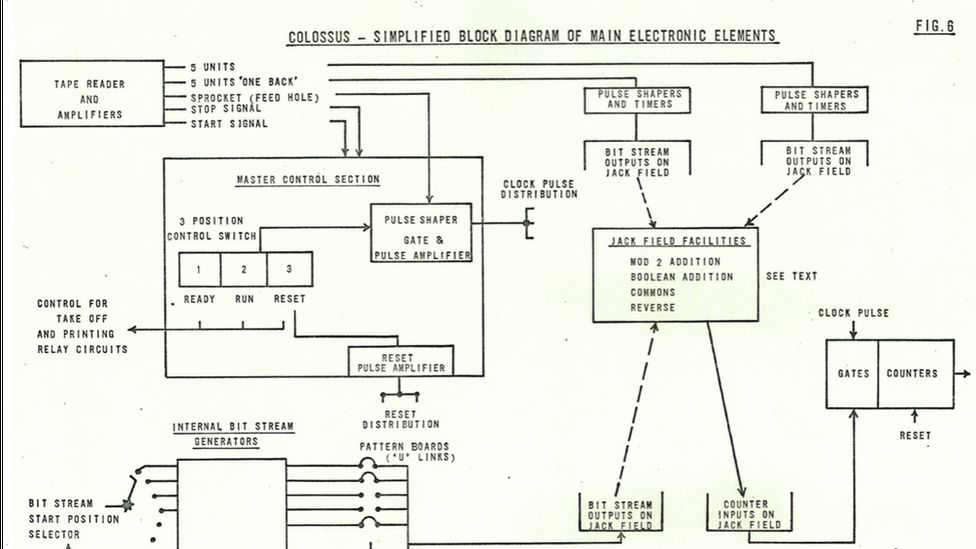

It says they “shed new light” on the “genesis and workings of Colossus”, which is considered by many to be the first digital computer.

Its existence was kept largely secret until the early 2000s.

Anne Keast-Butler, director of GCHQ, said the pictures were a reminder of the “creativity and ingenuity” required to keep the country safe.

“Technological innovation has always been at the centre of our work here at GCHQ, and Colossus is a perfect example of how our staff keep us at the forefront of new technology – even when we can’t talk about it”, she said.

The first Colossus began operating from Bletchley Park, the home of the UK’s codebreakers, in early 1944. By the end of the war there were 10 computers helping to decipher the Nazi messages.

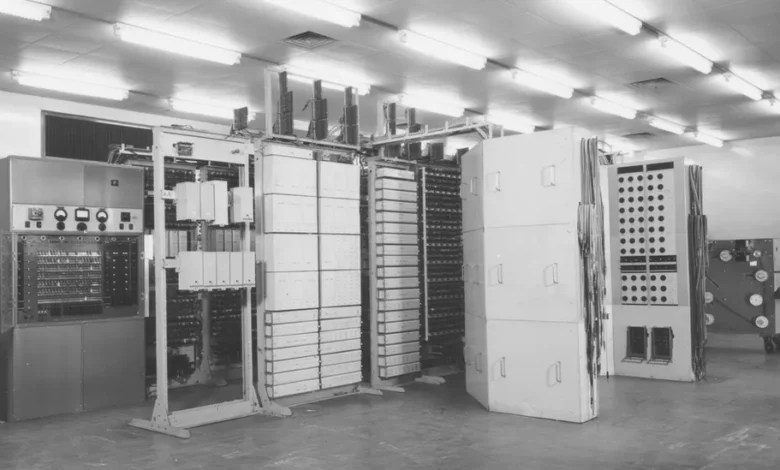

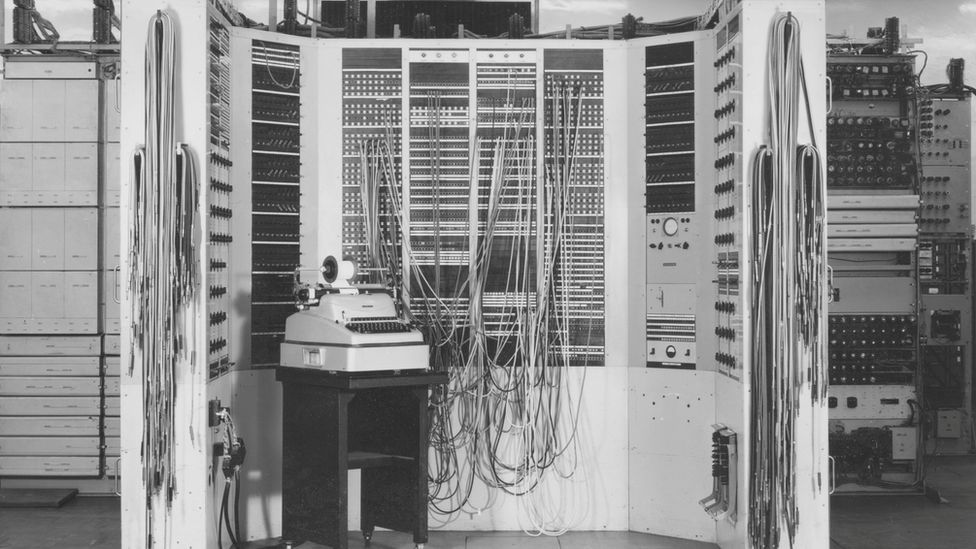

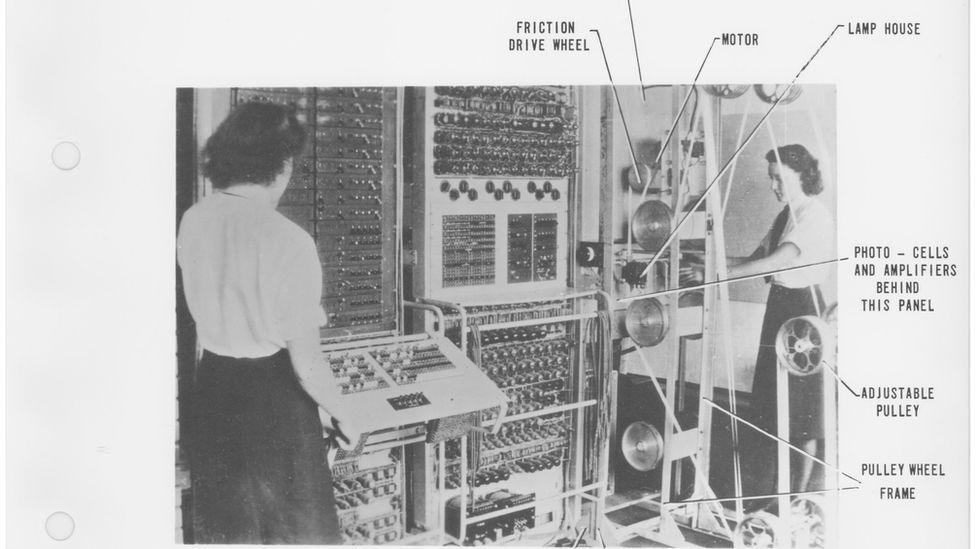

Fitted with 2,500 valves and standing at more than 2 metres tall, Colossus required a team of skilled operators and technicians to run and maintain it.

Often they were members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (Wrens) – one of the new images shows Wrens working on the machine.

Blueprints of its inner workings have also been made public for the first time, along with a letter referring to “rather alarming German instructions” intercepted by Colossus, as well as an audio clip of the machine at work.

By the end of the war, 63 million characters of high grade German messages had been decrypted by the 550 people working on the computers.

One of its notable successes was helping the Allies know that Hitler had swallowed the bait that the D-Day landings in June 1944 would be at Calais rather than Normandy.

Historians think the computers shortened the war and saved many lives.

In the dark

Despite its huge impact, engineers and codebreakers who had worked on the Colossus programme were sworn to secrecy and the existence of this vital piece of machinery was kept from the history books for almost six decades.

Colossus wasn’t formally acknowledged by the UK intelligence services until the 2000’s.

After the war eight of the 10 computers were destroyed.

The engineer who designed it, Tommy Flowers, was ordered to hand over all documentation on the machinery to GCHQ.

The attempts to keep it secret were so successful that Bill Marshall, a former GCHQ engineer who worked on Colossus in the 1960s, said he had no idea about its wartime role.

He said he was now “very proud to have been involved with Colossus even in just a small way.”

Andrew Herbert, chairman of trustees at the National Museum of Computing, which is based at Bletchley Park, said the release of the images was another opportunity to celebrate the lasting impact Colossus had had.

“From a technical perspective, Colossus was an important precursor of the modern electronic digital computer,” he said.

“Many of those who used Colossus at Bletchley Park went on to become important pioneers and leaders of British computing in the decades following the war, often leading the world in their work”, he added.