‘They give me hope’: Beating HIV stigma with community support in Zimbabwe

When Wonder Mwatamawenyu tested positive for HIV as a young man more than two decades ago, he thought he had signed his death warrant.

His society told him that HIV and AIDS, which were spreading rapidly in Zimbabwe in the 1980s and 1990s, had no treatment.

Mwatamawenyu tested HIV-positive in 2003 after going to donate blood at a health facility near his house in Matika village, just outside Mutare in eastern Zimbabwe. “I was shocked. I did not believe it,” the 51-year-old father of six told Al Jazeera.

“I later got sick and health workers encouraged me to take antiretroviral therapy (ART) medicine which I have been taking since 2004,” the tall, wiry man said, referring to the standard HIV treatment that was first rolled out in the country that same year.

Mwatamawenyu is one of about 1.3 million people living with HIV in Zimbabwe today. In the 20 years since he was diagnosed, much has changed.

When ART was first introduced around the world, patients used to take a combination of many drugs, but the treatment is now available in fixed-dose combinations that allow people to take just one or two pills. Taken every day for the rest of a person’s life, ART remains the most accessible HIV treatment globally because it is effective in stopping the virus from replicating in the body and is cost-effective, particularly in low-income communities.

Though ART does not cure HIV and AIDS – there is no cure – it helps patients’ immune systems and reduces mortality and morbidity. The disease is also no longer a death sentence, despite its seriousness.

AIDS-related deaths peaked in Zimbabwe in the 1990s and new HIV infections were high in the early 2000s when Mwatamawenyu was diagnosed. But the figures have declined over the years because of interventions like ART, and awareness campaigns on preventing mother-to-child transmission.

Stigma

Mwatamawenyu, who speaks at a million miles a minute, is the preacher of a small religious group. He said that when news reached his congregants that he had HIV, most left him.

“They thought I was dying. About 70 percent left. They thought I could transmit HIV to them just through a handshake.”

People became aware of his health status because of his frequent visits to the local clinic, walking distance from his home, to collect his medication and for routine checkups, Mwatamawenyu said.

He had also lost his father to AIDS in the mid-1990s.

While his congregants were afraid, his family was always supportive, particularly his mother.

“She encouraged me to take ART,” he said, also adding that his wife was HIV-negative but passed away in 2007 from an unrelated illness.

Born and raised in Chimanimani, some 150km from Mutare, Mwatamawenyu shares his story with others who are part of a group of people living with HIV from their village.

Group member Ruth Mlambo, a mother of four, tested HIV-positive in 2002 when a doctor revealed that her husband was positive and had been taking ART medicine.

“He hid it away from me. It was painful,” the 53-year-old former bookkeeper and healthcare worker said, recounting the distressing memories.

Mlambo said they kept the diagnosis a secret from the community at the request of her shy husband until he passed away in 2004. When she finally revealed she had HIV, she faced stigma and discrimination.

95-95-95

Last year Zimbabwe reached the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) target dubbed 95-95-95, whereby 95 percent of people living with HIV should be diagnosed while 95 percent of those living with HIV should be on ART medication and 95 percent of those should achieve viral suppression.

This helps in reducing HIV transmission and mortality as the 95-95-95 target results in 85 percent of all people living with HIV with viral load suppression, according to UNAIDS.

More than 1.2 million out of 1.3 million people living with HIV in Zimbabwe are on medication, according to government officials. About 97 percent of those have achieved viral suppression.

Over the years, the numbers of people dying from AIDS have also been declining. In 2002, 130,000 AIDS-related deaths were recorded compared with 20,200 in 2021, according to a report from the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Behind these strides in HIV prevention and treatment are men and women like Mwatamawenyu and Mlambo who fought hard to change their predicament.

Two years ago, there was a successful campaign to remove a law criminalising the wilful transmission of HIV, because research showed that women were being charged for this crime when venturing out in search of healthcare.

Recently the government tried to sneak it back into law, but lawmakers resisted and it was removed.

Daniel Molokele, chairperson for the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Health, told Al Jazeera they spoke strongly against it. The Ministry of Justice was trying to get it recriminalised to protect minors, but gender activists said criminalising sexually transmitted infections violates human rights and increases stigma.

“We hope that in the updated version of the bill that clause around wilful transmission will be totally removed,” Molokele said.

Evellyn Chamisa, the national coordinator for the Network of Zimbabwe Positive Women, an activist group, said involving all stakeholders – especially policymakers and beneficiaries in everything from prevention and treatment to awareness – made successful strides in achieving the UNAIDS target.

“Letting the people own the epidemic and put them in front in programming is important,” she said.

Community support

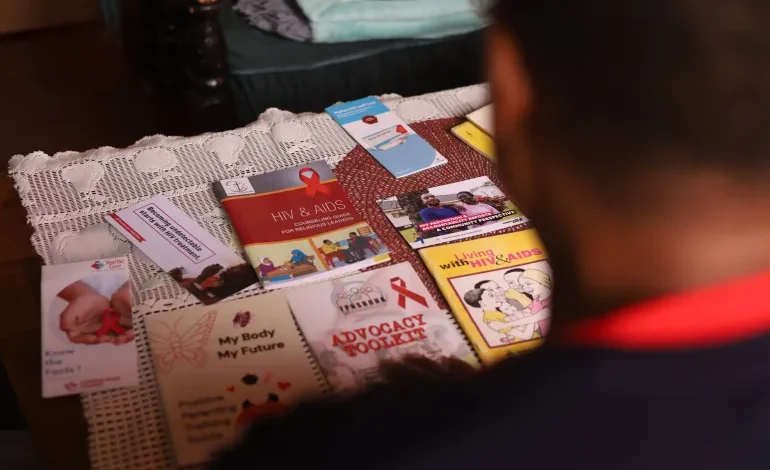

Community health groups like the one Mwatamawenyu belongs to create a platform for people living with HIV to get counselling, financial resources and other social support.

Back in 2004, he said the odds seemed impossible, but discovering there were many like him was a huge relief.

“I joined some groups of people living with HIV and this was a boost. I had developed low self-esteem. They gave me hope,” said Mwatamawenyu, his smile bright.

Looking at ease, Mlambo said she started taking ART medication in 2014 after falling sick, but HIV and AIDS-related awareness campaigns on radio and in the community changed her life.

She also took on entrepreneurship projects and started attending counselling sessions, she said, adding that the idea was to keep herself busy so that she did not stress.

Groups of people living with HIV share an unbreakable bond and where there is a bond there is hope, said Mlambo.

A devout Christian who goes to the Anglican Church, she is also popular in her village, having appeared on national TV talk shows, in church and on different platforms, inspiring many with her journey.

Martha Tolana, an HIV/AIDS activist, said while there has been great political will in the fight against the disease in Zimbabwe, HIV support groups provide a haven for people living with it.

“Providing peer counselling, advice and support on appropriate nutrition, treatment and adherence support, dealing with stigma and discrimination, as well as livelihoods support has been a game changer,” she said.

“Home-based care also started in the support groups,” Tolana said, referring to psychosocial support given to people living with HIV in their homes by informal or formal caregivers.

Zimbabwe has also been making progress in reducing mother-to-child transmission. It is mandatory for pregnant mothers to get tested for HIV and if they are positive, they get medication to prevent transmission to their unborn baby.

Though the current mother-to-child transmission rate is eight percent, which is still high, it has declined from 30 percent in 2004, according to UNICEF.