The undersea mountains where sharks rule

Under the vast undulating surface of the ocean, “constellations” of towering subsea mountains dot the Earth – and they are teeming with sharks.

Beneath the waves, ocean currents roar like the wind over the summits of long-extinct volcanoes. These seamounts rise steeply from the seafloor, soaring to heights of at least 1,000m (3,300ft). Some are pitted with craters, or lined with ridges. Others are topped with large, flat plateaus. Sometimes the peaks can even peep above the ocean’s surface, forming islands.

Seamounts are borderlands. Here, on the edge of the deep, reef-dwellers mingle with open-water species at every level of the food chain, from planktivorous fish to top predators.

Each seamount is unique and teeming with life. They bustle with corals, crustaceans, sponges, sea stars, fish, octopus, turtles, whales, dolphins, sharks and more. Compared to the flat seafloor, seamounts host a higher number and diversity of living creatures, many found nowhere else in the world. And there are likely many more yet to be discovered.

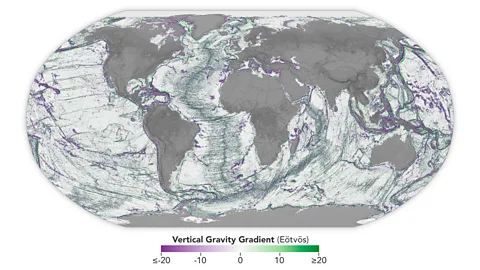

There are thought to be more than 100,000 undersea mountains spread across the globe – from the frozen waters of the North Atlantic to the abyssal depths of the tropical Pacific – but fewer than 0.1% have been explored.

“An unprecedentedly large number of volcanic seamounts have been found on the seafloor over the past couple of decades,” says Ali Mashayek, associate professor of climate dynamics at the University of Cambridge in the UK.

And today, as ocean exploration accelerates, more and more seamounts are being discovered. During one recent expedition to explore seamounts of the Atlantic Ocean, scientists discovered an unusual number of the ocean’s top predators: sharks.

“It was like living in a small village in the middle of nowhere,” says Sam Weber, who worked on the island of Ascension for seven years as its principal conservation scientist. “You know everyone. Not huge amounts to do, but good beaches, good diving, good walking.”

Ascension Island is “a tiny dot of green” halfway between Africa and Brazil, a lone speck of land in the tropical mid-Atlantic. But look beneath the waves of the seemingly endless ocean that surrounds the isle, and a different story emerges.

Ascension is the tip of an undersea volcano that has “breached the surface and become an island”, says Weber. It is just one in a chain of seamounts that stretches for hundreds of miles, “through St Helena and all the way to Africa – right across the Atlantic”.

Weber, now a lecturer in marine vertebrate ecology and conservation at the University of Exeter in the UK, explored three seamounts roughly 300km (186 miles) off the coast of Ascension Island. The summit of the Harris Stewart seamount is deep, only reaching as high as the twilight zone, the global layer of ocean which lies between the “sunlight” and “midnight” zones. At about 200 to 1,000m (650 to 3,300ft) depth, the twilight zone is bathed in perpetual dusky light.

The sister “Southern Seamounts” of Grattan and Young, on the other hand, are relatively shallow. Their peaks rise to around 100m (330ft) shy of the surface, and lie just 80km (49.7 miles) apart. These were “a very different place”, says Weber.

Why undersea ‘shark mountains’ are key to life on Earth

Alongside the British Antarctic Survey’s James Clarke Ross research vessel, Weber spent most of his 16 days at sea aboard a small longline fishing boat, catching and tagging sharks. “We were working with a crew of commercial fishermen – who were brilliant. They handled the catching very effectively, and then we did the tagging work. We all worked together, cooked together, ate together, slept together.”

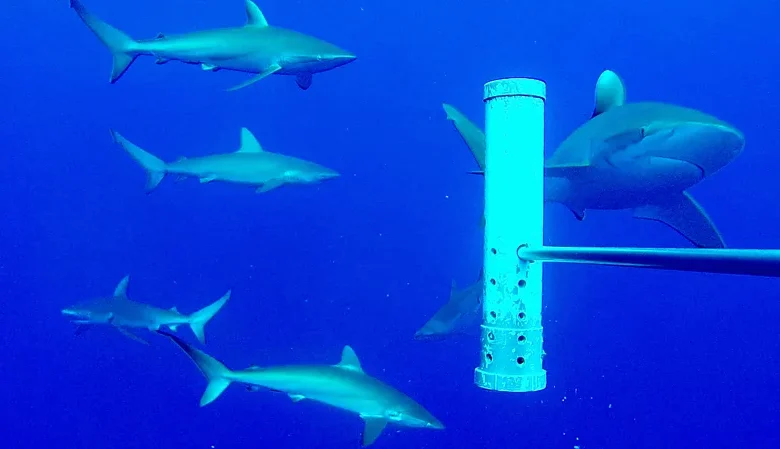

It was on the Southern Seamounts that the Weber and his colleagues found a whopping 41 times more sharks, in terms of biomass, than out in the open ocean.

Compared to surrounding oceanic waters, Weber and his team found the Southern Seamounts supported five times higher diversity, and 30 times higher biomass, of sharks and large predatory fishes combined. There was also a significantly higher number of several threatened and near-threatened species – including silky sharks – and commercially exploited species such as yellowfin and bigeye tuna.

These boom-bust fisheries turn up and go, ‘Whoa, there’s loads of fish’. They scoop them all up, and they’re gone – Sam Weber

“Sharks, including deep-sea and migratory sharks, love to be around seamounts – across all the global oceans,” comments Lydia Koehler, an expert in ocean governance and associate lecturer at Plymouth University School of Biological and Marine Sciences in the UK.

Why seamounts attract so many top marine predators, though, remains somewhat of a mystery.

A planet-sized world map made of giant magnets

It is thought animals may visit seamounts for shelter, cleaning or food. Or they could use them as landmarks for navigation.

A seamount forms when volcanic rock, containing tiny iron atoms, cools and solidifies. The iron atoms – which become aligned with the local magnetic field of the Earth – are frozen in time and the seamount’s unique magnetic field is locked in. Both whale and shark species may use seamounts’ unique geomagnetic signatures as waymarkers, says Weber.

“Seamounts have a really strong magnetic signature that a lot of these species are attuned to,” he says. “The seamounts we looked at are at the tip of a very long chain of seamounts, all about 100 to 200km (62 to 124 miles) apart. We’re really interested to find out whether [animals] are using them as stepping stones along their migratory corridor.”

Then there are the creatures that call seamounts home. There are two theories that could explain this predator-aggregating effect of seamounts: the oasis and hub hypotheses.

“All the life on the seamounts, including the predators at the top of the food chain, are a concentration of energy,” explains Weber. “That energy can come from two main places. Either it can be generated on the seamount itself – so the seamount is creating or concentrating energy. This is the oasis hypothesis, meaning, the seamount is like an oasis that supports and nourishes life. “Or the seamounts are acting as gathering places for animals that are feeding elsewhere, then bringing that energy back to the seamount,” says Weber – which is the hub hypothesis.

Stirring rods of the ocean

In 1998, pioneering oceanographer Walter Munk described seamounts as “the stirring rods of the ocean”, which could help explain how a seamount might become a fertile, nourishing oasis.

The deep waters around a seamount can be chaotic and turbulent. When ocean currents hit the steep slopes of an undersea mountain, water is forced up and over the summit, thrusting the cold nutrient-rich water towards the sunlit surface.

“We have realised that the turbulence generated by the interaction of oceanic deep flows with these seamounts plays a significant role in driving deep ocean circulation,” says Mashayek. In fact, according to Mashayek and his team, the stirring around seamounts contributes to roughly a third of all global ocean mixing.

“Seamount-induced mixing,” adds Laura Cimoli, physical oceanographer at the University of Cambridge and co-author of the paper, “exerts control on the deep ocean storage of natural and anthropogenic properties – such as nutrients, oxygen, heat and carbon.”

As the deep water is forced to the surface, the sudden upwelling of nutrients results in blooms of phytoplankton – tiny marine plants which are the first link in ocean food chains. And the seamount becomes a fertile oasis which, in turn, attracts larger predators like sharks.

However, Weber found little evidence of increased primary productivity of phytoplankton at the Ascension seamounts. Instead, an increase in biomass over seamounts of animals in the low and mid-levels of the food chain was driven mainly by vertically migrating mesopelagic species – creatures rising up from the twilight zone.

Filter feeders, says Weber, may benefit from prey being concentrated at one point on the peak – a process known as “trophic focussing”.

“Seamounts can act like giant traps for planktonic organisms that are blown across it constantly,” says Weber. “And, as this plankton moves up and down, the seamount can trap it on the summit. [The energy] then cascades up through the food web, to all the things above it.”

The ‘service station hypothesis’

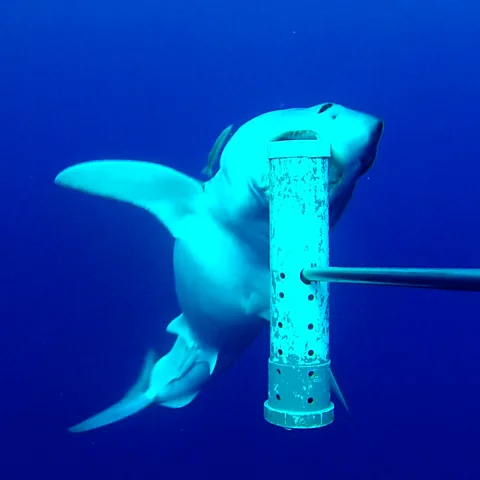

And, while some individual animals are “resident” – calling a particular seamount home for most of the time – Weber’s findings suggest some species, such as Galapagos and silky sharks, as well as yellowfin and bigeye tuna, gather at seamounts after foraging in the open ocean.

“The energy is generated off the seamount and the foragers – the mobile predators – go and collect it and bring it back.” This is where “hub theory” comes in: that seamounts may act as a place to gather, socialise, mate or rest, or a base to return to after hunting in the open ocean.

There are a few particular spots on the seamounts that the sharks seem to prefer, continues Weber. “You get very large numbers all aggregating in that one location. Maybe those are the thermal areas, the energetically favourable areas, where everyone wants to gather to swirl and save energy.”

This, says Weber, is his favourite hypothesis – which he calls the “service station hypothesis” – and one that he hopes to investigate further. “We want to test if they use [seamounts] as an energy-saving refuge.” Many species of shark need to swim constantly in order to keep pumping water over their gills. “The fact that they can’t stop swimming incurs an energetic cost.”

So, much like an eagle soaring on a thermal updraft in the sky, Weber thinks the same may be happening as water wells up around the seamounts. This upwelling could allow sharks to float and save energy while they’re not feeding, “then they go back off and feed in the blue again”.

One particular silky shark the team tagged left the seamount every night to forage, travelling up to 100km (62 miles). “They can obviously navigate to these seamounts very effectively,” says Weber. “They can swim for long periods of time and then, quite quickly, they can beeline straight back to again. Then, off they go again.”

The silky shark they observed moved in a figure of eight pattern on its foraging trips. But why it would behave in such a way, Weber says, remains unknown. “Maybe it’s to hold its position in the ocean, or – I don’t know – to check in with other silky sharks? I don’t know why it kept coming back. But it supports the hub theory.”

One thing the researchers do know is that some of the tagged silky sharks vanished from the seamount for around a year. “Which would suggest they are using them as almost like a service station,” says Weber. “On a long journey, they check in, maybe feed, then carry on their migration. They’ve got a long way to go, and [seamounts] have loads of food, so they just stop off as they go.”

The halo effect

It seems both oasis and hub theories may apply to seamounts – with a mixture of resident populations, regular visitors, as well as some that are just passing through.

The study also found these remarkable habitats influence the oceans that surround them. A “halo” of increased marine life was found to extend far beyond the summits – spreading at up to 6km (3.7 miles) into the open ocean. Other studies have found this halo effect could extend as far as 40km (25 miles) into the open ocean.

“You can go kilometres away [from the summit] and still find higher predator abundance,” says Weber. “And it’s very deep by that point – thousands of metres deep.”

Silky sharks, yellowfin tuna, and bigeye tuna travelled hundreds of kilometres from seamount summits but seemed to remain “site-attached”, says Weber. Acoustically tagged Galapagos and silky sharks were also seen to travel the 80km (50 miles) between the two Southern Seamounts, as if they considered both the two summits home.

Meanwhile, silky sharks moved off the seamount summits at night only to return at dawn – indicating the “halo” of enhanced predator abundance expands and contracts in unison with night and day.

“So, it’s a zone of enrichment, and they connect to each other. When you’re thinking about protected area design, you need to be thinking bigger than just the summit itself,” says Weber.

Evidence is mounting that shows seamounts are irreplaceable oases of biodiversity in the deep ocean and of vital importance to elasmobranchs – which include sharks, rays and skates – some of the most endangered animals on the planet.

“Sharks are a crucial part of the entire marine ecosystem, from shallow to deep, from coastal to offshore,” says Koehler. “With over a thousand species, you can imagine each of those single species has their own role to play.”

But gathering together in one place is risky. For decades, seamounts – where desirable fish like the bigeye tuna can readily be found – have been subject to bottom trawling by industrial fisheries.

“The biggest threat to sharks is overfishing,” says Koehler. “That includes commercially targeted fishing, but also bycatch. This is where they don’t intentionally go for sharks – but due to the gear they use and the places they go, they do catch a lot of sharks. And they land them, and market them.”

Bycatch is one of the five biggest threats to life in the ocean, and sharks are amongst the most vulnerable. It’s not known how many sharks are killed by commercial fisheries every year but the number is thought to be in the hundreds of millions.

Bottom trawling is a particularly destructive method of fishing, says Koehler. “A heavy net, that’s weighed down, is dragged across the seafloor,” she explains. “You can imagine how much damage that does to the fine sponges, the corals, all those really fragile ecosystems. You basically remove them. And what you’ve got left is just a bare field of nothing.”

Everything in the fishers’ path is scraped up from the ocean floor, not just the target species but any species that happens to be there.

“Bottom trawling demolishes the benthic ecosystem. The whole food web – decimated,” adds Weber, “And a lot of these species that live on seamounts are very slow-growing. They have very slow life histories. Then these boom-bust fisheries turn up and go, ‘Whoa, there’s loads of fish’. They scoop them all up, and they’re gone.”

The impact of bottom trawling on seamounts can last for decades, adds Koehler. “It will take more than a human’s lifetime – more than multiple lifetimes – for these ecosystems to regenerate and to recover. And in the meantime, you remove these really important services: food sources, nursery grounds. They are not functional anymore for those species that really depend on them.”

However, knowing where sharks gather is also vital knowledge for advancing conservation. In 2024, Emanuel Gonçalves, chief scientist at the Oceano Azul Foundation led an expedition to the Gorringe Seamount, Western Europe’s tallest – albeit underwater – mountain, off the coast of Portugal. The following year Portugal’s government announced the creation of a new protected marine area.

“Seamounts rise thousands of meters from the abyssal plains and attract or are home to a myriad of ocean life,” says Gonçalves. “Deep water corals and sponges can live for thousands of years on their slopes. Deepwater fish and invertebrates, whales, sharks and tuna – and many [species] still undescribed to science. Seamounts are unique and need to be protected. “

In the Ascension Islands, too, the entire Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) was closed to commercial fishing in 2019. In 2021, the United Nation’s Second World Ocean Assessment stated, “Fishing, especially bottom trawling, constitutes the greatest current threat to seamount ecosystems.” And, in October 2025, the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s “Motion 032” was adopted – calling for a global transition away from bottom trawling on seamounts by the end of 2026.

However, Weber says, preventing bottom trawling alone is not sufficient as top predators are often caught by pelagic longlines too. “Predators are the species that have been hammered most by commercial fishing. I would definitely be supportive of having at least some seamounts shut down altogether, like we’ve done in Ascension Island. Get rid of trawling, get rid of longline fishing. Protect the whole ecosystem.”