The sounds revealing the secrets of world’s most elusive whales

Beaked whales have rarely been seen. Now scientists are using underwater sounds to help identify these mysterious creatures.

On a bright, almost windless day in early June 2024, scientist Elizabeth Henderson was aboard a boat off the sun-drenched coast of Baja California. She and her team perched halfway up the vessel’s mast, wielding powerful binoculars and peering round at the calm water.

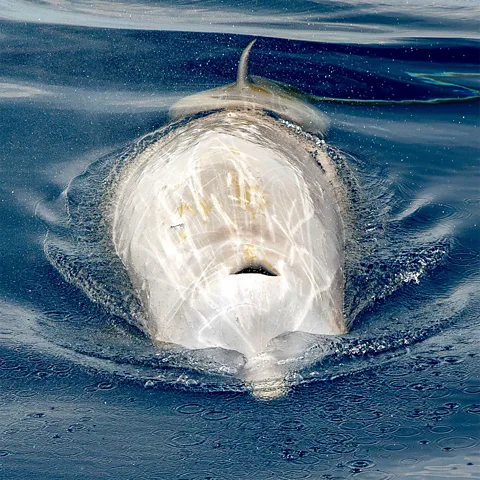

They were looking for beaked whales, a group of species that aren’t often sighted because they dive deeper and longer than any other mammal – with some known to dive nearly 2 miles (3km). Even when they surface, their relatively small, light grey bodies are hard to spot. “Depending on the light, they could just look like a wave,” Henderson says.

It was a few days into their expedition, and Henderson and her team had no luck. But then a cry came up from the boat below – it was the captain, whose eyes were on the water closer to the vessel. “There’s a whale next to us!” he exclaimed. It was actually a pair of juveniles, and they were swimming alongside the boat.

“One assumption about beaked whales that has always been made is that they don’t like boats,” says Henderson, a bioacoustic scientist at the US Navy Marine Mammal Programme where she studies the vocalisations and behaviour of marine mammals. “But they were not boat-shy at all. They were curious about us.”

Little is known about beaked whales. Currently 24 species are known to science, thought to make up around 25% of all whale and dolphin species. Some species have never been seen alive, and are only known about because their bodies have washed up on the shore. But new ways of listening to them, and more studies that are capturing their distinctive underwater clicks and squeaks, are slowly revealing the secrets of the world’s most elusive whales.

Henderson’s sighting came as a surprise in more ways than one. Based on sound alone, the team weren’t expecting to come across this beaked whale species. They had heard the BW43 pulse (BW for “beaked whale”, with a peak frequency of 43kHz), thought likely to be associated with the endangered Perrin’s beaked whale. But they took a biopsy, and the lab results would later reveal that this was another species: the gingko-toothed beaked whale, named after the distinctive gingko-leafed shape of its teeth.

“It was amazing, it was so unexpected – and for a species that has never been seen alive in the water, or in the wild. It’s a family of species that you assume you’re never going to see up close. To have them right next to us was the coolest thing ever,” says Henderson.

Beaked whales’ long, deep dives mean they’re difficult to study, explains Oliver Boisseau, senior research scientist at Marine Conservation Research, a UK non-profit. “Beaked whales have traditionally been overlooked,” he says. “They’re often offshore, they’re hard to access, and they’re cryptic, which means they’re hard to see.”

It’s quite something in the 21st Century to still be discovering new mammal species that are the size of family cars – Oliver Boisseau

A new species, Ramari’s beaked whale, was discovered as recently as 2021. “It’s quite something in the 21st Century to still be discovering new mammal species that are the size of family cars. It’s quite mind-boggling,” Boisseau says.

Recent scientific interest has been prompted by mass strandings, thought to be caused by navy sonar. Scientists don’t understand the exact relationship between sonar and beaked whales, but one theory is that navy sonar prompts the mammals to surface too quickly, causing bubbles in their blood similar to when scuba divers suffer from “the bends”. “There’s sudden strong interest in this quite acute conservation challenge,” Boisseau says.

It is sound that is harming the whales – but it is also sound that is helping science understand them. “They rely primarily on their acoustics,” Boisseau says – they make and listen to sounds to help them forage, mate and navigate. “This is really how they interpret the world around them. So that’s an excellent window into their world below the water.”

Using microphones placed anywhere from 10 to nearly 5,000m (33-16,400ft) underwater – called hydrophones – scientists are listening to beaked whales’ echolocation clicks and buzzes, which they use to navigate the dark ocean depths. Each species has a unique echolocation pulse, creating an audio signature that tells scientists which is which.

In the initial identification of a species, genetic analysis is important, too: scientists use a crossbow to take a skin biopsy, and collect water samples to analyse environmental DNA. For Henderson’s identification of the gingko-toothed beaked whale, this genetic material was “the missing piece that we needed,” she says. Taking this material comes with important ethical considerations, but thankfully only needs collecting once. “It does have the potential for possible injury,” Henderson says. “So as research scientists, we don’t want to be casual about it.”

A microphone, on the other hand, doesn’t cause harm. “It’s not impacting them at all, because it’s just passively listening,” Henderson says – especially when it’s stationary in the water, independent of a boat. “Once we have the genetics and we’ve confirmed what echolocation pulse goes with what species, we don’t need the genetics anymore. We just need the bioacoustics. We almost don’t even need to see them anymore, because we can just listen.”

And when an animal spends as much time deep below the surface as beaked whales do, hearing them is dramatically easier than seeing them. There’s no need for a vessel, or calm conditions. “You’re able to put acoustic recorders out and get data on any species of beaked whale that’s out there. You can get all the information that you need about a species just using passive acoustic monitoring,” Henderson says.

Other studies have involved tagging the whales, capturing acoustic data during their day-to-day movements. This has revealed how they forage for food: beginning to send out clicks only once they’re deep underwater, where they use sonar to locate squid and fish to eat. Their clicks speed up to a buzz when they get closer to their prey, helping them locate it precisely.

Tagging studies have also revealed that young beaked whale calves start deep diving much earlier than other types of whale. “You have this tiny calf, but they go down on a dive with the mum and often it’s quite a long dive. Everything the beaked whales seem to be doing is really pushing the limits of what’s achievable with their biology,” Boisseau says.

A priority for studies is to find out which beaked whales live where. “We’re just getting a handle on the basic question right now of who everybody is and where everybody’s distributed,” Henderson says. Her sighting of the ginkgo-toothed beaked whale off California was unexpected – this species was thought only to live on the other side of the Pacific, towards Japan and New Zealand.

Boisseau has conducted acoustic surveys on both sides of the Atlantic, in the Mediterranean Sea, and the Indian Ocean. His goal is to count the whales and to find out how many of them live in which areas. But for now, population data is limited – which means we don’t know which populations are under threat. Because of this, Boisseau says, it’s important that scientists “err on the side of caution”.

“It’s frustrating that we should really be pushing to protect these species in a more robust fashion, but we just don’t have the numbers to say, ‘this species is at threat of extinction’,” he says.

Learning which species are under threat is important if we’re to prevent harm to them. Navy sonar continues to be a concern, though it has been banned in the Canary Islands following multiple mass strandings there. No stranding events have happened since the ban was introduced in 2004. “We feel that [banning navy sonar] may be very effective. But it’s a dicey conversation to have in terms of national security,” Boisseau says. Since 2016, there have also been some restrictions on navy sonar in waters near Hawaii and California.

Fishing is becoming another issue, Boisseau adds. “Beaked whales are beginning to get caught a bit more in [shallow] fishing nets. Maybe there’s more we can be doing to mitigate the effects of fishing on these species of which we know so little.”

Plastic is another problem for whales, even at deep depths. They’re mistakenly eating plastic bags, ropes and bottles, because the acoustics of plastic debris are similar to the squid they’re looking for.

Preventing harm to beaked whales is important in its own right. But protecting these whales also has wider benefits. They recirculate nutrients around the ocean – a process known as the “whale pump”. By feeding on squid and fish deep in the water and then defecating at the surface, “they’re bringing carbon and nutrients from the depths”, Boisseau explains. This feeds phytoplankton, which play a huge role in taking up carbon and sinking it in the ocean. “This whale pump phenomenon can be a very useful tool in helping us to tackle the climate crisis,” Boisseau says. One whale can capture an average of 33 tonnes of carbon dioxide over its lifespan.

There’s much more to learn about the mysterious lives of beaked whales – their habits, their hardships, their relationships. Listening to the deep is likely to give scientists more clues, and more data to piece together. “To put [the data] together and solve that puzzle is a very exciting thing,” Henderson says.

And in a changing ocean – one that is warming, and filled with plastic – this understanding can’t come fast enough. “They are just fascinating creatures,” Boisseau says. “We really want more people to know about them and care for them.”