The secret sauce for Taiwan’s chip superstardom

When 23-year-old Shih Chin-tay boarded a plane for the United States in the summer of 1969, he was flying to a different world.

He grew up in a fishing village surrounded by sugarcane fields. He had attended university in Taiwan’s capital Taipei, then a city of dusty streets and grey apartment buildings where people rarely owned cars.

Now he was off to Princeton University. The US had just a put a man on the Moon and the Boeing 747 in the skies. Its economy was larger than those of the Soviet Union, Japan, Germany and France combined.

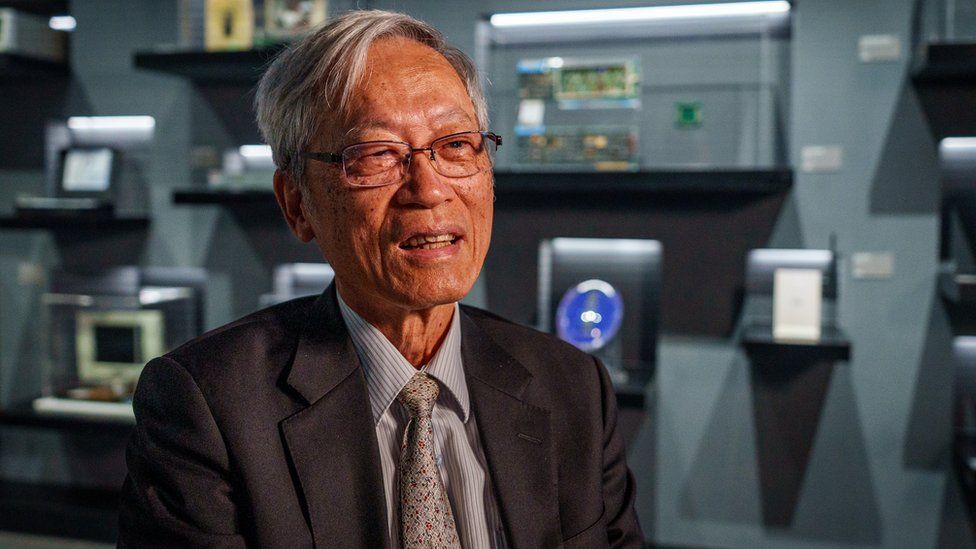

“When I landed, I was shocked,” Dr Shih, now 77, says. “I thought to myself: Taiwan is so poor, I must do something to try and help make it better off.”

And he did. Dr Shih and a group of young, ambitious engineers transformed an island that exported sugar and t-shirts into an electronics powerhouse.

Today’s Taipei is rich and hip. High-speed trains zip passengers along the west coast of the island at 350km/h (218mph). Taipei 101 – briefly the tallest building in the world – towers over the city, an emblem of its prosperity.

Much of that is down to a tiny device no larger than a fingernail. The silicon semiconductor – wafer-thin and best-known now as a chip – sits at the heart of every technology we use, from iPhones to airplanes.

Taiwan now makes more than half the chips that power our lives. Its biggest manufacturer, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), is the ninth-most valuable business in the world.

That makes Taiwan nearly irreplaceable – and vulnerable. China, fearing it could be cut off from the most advanced chips, is spending billions to steal Taiwan’s crown. Or it could take the island, as it has repeatedly threatened to do.

But Taiwan’s path to chip superstardom will not be easy to replicate – the island has a secret sauce, honed through decades of laborious work by its engineers. Plus, the manufacturing relies on a web of economic ties that the escalating US-China rivalry is now trying to undo.

Sugar to silicon

When Dr Shih arrived at Princeton, “the US was just beginning the semiconductor revolution”, he says.

It had just been a decade since Robert Noyce made the “monolithic integrated circuit”, packing electronic components onto a single wafer of silicon – an early version of the microchip which kickstarted the personal computer revolution.

For the two years after Dr Shih graduated, he designed memory chips at Burroughs Corporation, second then to IBM in computer-making.

At the time, Taiwan was hunting for a new national industry following an oil crisis that had pummelled its exports. Silicon seemed like a possibility – and Dr Shih thought he could help: “I thought it was time to come home.”

In the late 1970s, he joined Taiwan’s best and brightest electrical engineers at a new research lab – the staid-sounding Industrial Technology Research Institute would play an outsized role in recasting the island’s economy.

Work began in Hsinchu, a small city south of Taipei – today it’s a global electronics hub, dominated by TSMC’s enormous fabrication plants. These chip factories, each the size of several football fields, are some of the cleanest places on earth. The finer manufacturing details are a well-guarded secret, and no outside cameras are allowed.

The newest factory – the nearly $20bn fab 18 in southern Taiwan – will soon start producing three-nanometre chips destined for next-generation iPhones.

All of this is far beyond what Dr Shih and his colleagues imagined when they opened an experimental factory in the 1970s. They were hopeful because they had technology licensed from a major US electronics maker – but to everyone’s surprise, the factory outperformed its parent. It’s hard to explain why and, to this day, the precise formula for Taiwan’s success remains elusive.

Dr Shih’s recollection is more prosaic: “Output was better than the original RCA plant, with lower costs. So, this gave the government confidence that maybe we really could do something.”

The Taiwanese government put up the initial capital – first for the United Micro-electronics Corporation, and then in 1987 for what would become the world’s biggest chip factory – TSMC.

To run it, they recruited Morris Chang, a Chinese-American engineer and former executive at US electronics giant Texas Instruments. It was a stroke of luck or genius, or both – today the 93-year-old is known as the father of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry.

Back then, he quickly realised that taking on US and Japanese giants at their own game was a losing proposition. Instead TSMC would only manufacture chips for others, and not design its own.

This “foundry model”, which was unheard of in 1987, changed the landscape of the industry and paved the way for Taiwan to become the pack leader.

And the timing couldn’t have been better. Silicon Valley’s new crop of start-ups – including Apple, Qualcomm, Nvidia – did not have the funds to build fab plants of their own. And they would struggle to find manufacturers for the chips that they couldn’t function without.

“They would have to go to leading semi-conductor companies and ask if they had any excess production capacity they could use,” Dr Shih says. “But then TSMC came along.”

Now California’s “fabless” companies could partner with Taiwan’s chip makers, who had no interest in stealing their designs or competing with them.

“Rule number one at TSMC is don’t compete with your customers,” Dr Shih says.

The secret sauce

The world produces more than a trillion chips a year. A modern car has anywhere between 1,500 to 3,000 chips. The iPhone 12 reportedly had around 1,400 semiconductors. A shortfall in 2022, driven by soaring demand for electronics during the pandemic, hit sales of washing machines and BMWs alike.

Taiwan’s extraordinary success – the island ships more than half of those trillion-plus chips, and nearly all of the most advanced ones – has been driven by its mastery of volume. In other words, Taiwanese manufacturing is incredibly efficient.

Making silicon chips is expensive and painstaking. It starts off with a large ingot of ultra-pure silicon grown from a single crystal. Each ingot may take several days to grow and could weigh up to 100kg.

After a diamond cutter slices the slab into skinny wafers, a machine uses light to etch tiny circuits onto each wafer. A single wafer may contain hundreds of microprocessors, and billions of circuits.

What matters eventually is the yield – the area of each wafer that is usable as a chip. In the 1970s US companies had yields as low as 10% and, at best, 50%. By the 1980s the Japanese were averaging at 60%. TSMC has reportedly surpassed them all with a yield that hovers around 80%.

Over time Taiwanese manufacturers have managed to cram more and more circuits into mind-bogglingly smaller spaces. Using the latest extreme-ultraviolet light lithography machines, TSMC can etch 100 billion circuits on to a single microprocessor, or over 100 million circuits per square millimetre.

Why are Taiwanese companies so good at this? No-one seems to know exactly why.

Dr Shih thinks it’s simple: “We had brand new facilities, with the most up-to-date equipment. We recruited the best engineers. Even the machine operators were highly skilled. And then we didn’t just import technology, we absorbed the lessons from our American teachers and applied continuous improvement.”

A young man who spent several years working at one of Taiwan’s largest electronics companies agrees: “I think Taiwan’s companies are bad at making big breakthroughs in technology. But they are very good at taking someone else’s idea and making it better. This can be done by trial and error, continuously tweaking small things.”

This is important because in a semiconductor fab the machines need to be constantly calibrated. Making microchips is engineering. But it’s also more than that. Some have likened it to cooking – like a gourmet feast. Give two chefs the same recipe and ingredients – the better cook will make the better dish.

In other words, Taiwan has a secret sauce.

But the young man, who did not want to reveal his name, or that of the company, says Taiwanese companies have another advantage.

“Compared to software engineers in the US, even at the best companies here, engineers are paid quite badly,” he said. “But compared to other industries in Taiwan the pay is good. So, if you work for a big electronic company after a few years, you’ll be able to get a mortgage, buy a car. You’ll be able to get married. So, people suck it up.”

He described a six-day week which began each day with a meeting at 07:30 and would usually last until 19:00. He would also be called in on Sundays or holidays if there was a problem at the plant.

“If people weren’t willing to do the job the company would be finished. It’s because people are willing to put up with hardship that these companies succeed.”

The silicon shield

In December 2022 TSMC broke ground on a $40bn plant in the US state of Arizona. It was hailed by President Joe Biden as a sign that high-tech manufacturing was returning to American soil.

Since then the headlines have been somewhat less cheery.

They Wouldn’t Listen To Us: Inside Arizona’s Troubled Chip Plant, read one. Another said, TSMC Struggles To Recruit Workers While Facing Pushback From Unions.

Chip production was supposed to start next year. Now it’s been put back to 2025.

Former TSMC chairman Dr Chang was deeply sceptical from the start. Last year he described expanding chip production in the US as an “expensive, wasteful exercise in futility” because manufacturing chips in the US would be 50% more expensive than in Taiwan. But Taiwan’s chip-making prowess has put it at the centre of the tech war between the US and China.

Washington wants to prevent Taiwan supplying China with the cutting-edge chips it fears Beijing will use to accelerate its weapons programs and advance its artificial intelligence.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which strangled Europe’s gas supply, US politicians are jittery about Taiwan. They fear that the huge concentration of high-end chip production on the island makes the US economy hostage to a Chinese invasion.

But Taiwanese companies see little economic advantage in moving production off the island. They are doing so reluctantly under political pressure.

People in Taiwan resent the idea that they should be blamed for their success – and that Taiwan should voluntarily weaken what many regard as its “silicon shield”, while the rest of the world vacillates over whether the island and its democratic society is worth protecting from Chinese aggression.

Dr Shih says those who are seeking to forcibly restructure global chip production misunderstand its success.

“If you look at the history of semiconductors, no one country dominates this industry,” he says. “Taiwan may dominate the manufacturing sector. But there is a very long supply chain and innovation from every part of it contributes to the growth of the industry. “

Much of the world’s raw silicon comes from China, although most of it goes to the solar industry. Germany and Japan lead the charge in chemicals that are necessary to process the wafers.

Carl Zeiss, a German optoelectronics company better known for making eyewear and camera lenses, produces optical devices that go into the lithography machines made by a leading Dutch company, ASML. The laborious manufacturing works to designs that originate in American companies or the UK-based Arm.

Dr Shih is doubtful Beijing can recreate this supply chain – from materials to design to high-end production – inside China.

“If they want to create a different model then I wish them luck,” he says with a shrug. “Because if you really want innovation, you need everyone to work together from all around the world. It’s not one company or one country.”

He is just as doubtful about cutting China out as the US has been doing.

“I think that’s probably a major mistake,” he says. “When I look back, I feel lucky to have witnessed the extraordinary growth of Taiwan’s economy and this long period of peace. Now I see conflict in other parts of the world, and I worry it may come to Asia.

“I hope people appreciate the precious effort that we made and won’t destroy it.”