The problem with British policing is not ‘just a few bad apples’

Marienna Pope-Weidemann

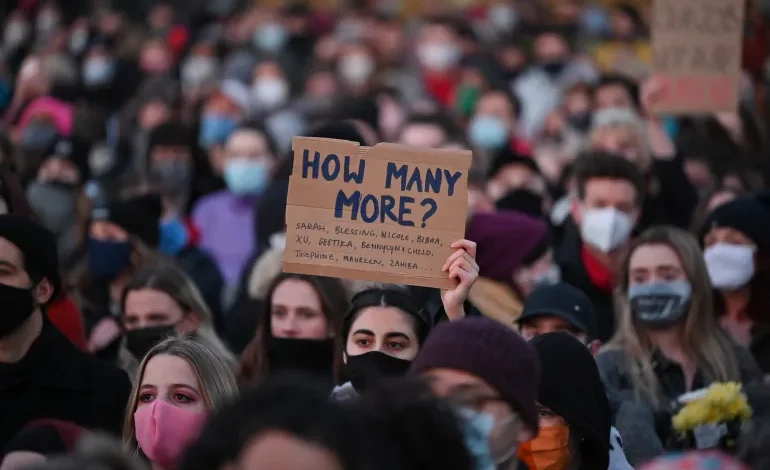

On February 29, an independent inquiry into the abduction, rape and murder of Sarah Everard by an off-duty police constable in London published its first damning report.

The Angiolini Inquiry focussed on the “career and conduct” of the murderer Wayne Couzens, who used his police warrant card and police powers to convince Sarah to get into the back of his car during a COVID-19 lockdown in March 2021. It found that he should never have been allowed to become a police officer let alone remain in the force for 20 years.

Metropolitan Police “repeatedly failed” to spot warning signs about his unsuitability to be an officer, the inquiry said. The many offences he has been accused of throughout his life include a serious sexual assault against a child before the beginning of his policing career and multiple counts of indecent exposure. According to the inquiry, one indecent exposure charge, to which he pleaded guilty, had occurred just days before Sarah’s murder. The police force consistently turned a blind eye to Couzens’ predatory behaviour, the report found, and missed multiple opportunities to stop him. Sarah’s family said if not for these failures, she would still be alive today.

The damning picture painted in the report – one of police incompetence, institutional misogyny and systemic apathy towards sexual violence – is devastating and truly frightening but what it is not is surprising.

After all, Metropolitan Police Commissioner Mark Rowley himself admitted in September that the force readily employs “hundreds” of officers who should have been sacked for misconduct. And another independent review tied to the Everard murder, this time looking into “the standards of behaviour and internal culture of the Metropolitan Police Service” and published in March 2023, found that it is “institutionally racist, misogynistic and homophobic”.

Although multiple inquiries have been restricted to scrutinising London’s Metropolitan Police, in truth this is a national issue. As thousands of women and girls harassed, abused, victimised and failed by police across the country know too well, if we were to broaden the scope of such inquiries and reviews, we would see many, if not most, police forces across the country are crippled by misogyny, racism and indifference to sexual violence.

Indeed, according to a 2023 report by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), from October 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022, at least 1,483 unique allegations of violence against women and girls were recorded against 1,539 police employees. Last year, even the former head of the so-called Independent Office for Police Conduct – the watchdog we rely on to protect us from police corruption and abuse – was charged with raping a child.

Sarah was the victim of a national crisis of policing that threatens public safety and wellbeing. Police routinely fail to apprehend repeat abusers like Couzons before their behaviour escalates to murder, and this failure is not limited to predators among their own ranks. On average, two women are killed by their domestic partners each week, often after contacting police or other public services and asking for help.

According to a new report by the NPCC, from April 2022 to March 2023, police recorded 242 domestic abuse-related deaths in England and Wales, including 93 suspected victim suicides. There are many ways that the trauma of abuse can change or take a life, particularly when that trauma is amplified by a discriminatory state response. Countless are lost to suicide and addiction related to the impact of prolonged abuse by their abuser(s) and neglect by the state. In this country today less than one in 100 rape cases lead to conviction; less than two in 100 are even being charged.

I have heard the same story of neglect, discrimination and corruption from more survivors than I can count. People started sharing their stories with me when I started speaking out and campaigning for change following the loss of my cousin Gaia. She was 19 years old in November 2017 when she died of hypothermia after going missing in Dorset during a mental health crisis. This was less than two years after reporting to Dorset police that she was a victim of child exploitation. Like so many others, the police in Dorset repeatedly failed to listen to Gaia or take action to keep her safe and this paved the way for her preventable death.

They failed to fully investigate Gaia’s and others’ allegations against the known child sex offender she accused of rape, refused her a restraining order and failed to make so much as a safeguarding referral despite innumerable pleas for help. She went missing just a few hours after a police officer hung up on her, accusing her of talking “a load of rubbish”. She was already dead when they finally agreed to start properly searching for her.

Just like London Met, Dorset Police has an an appalling record of investigative failure and harbouring perpetrators. A Dorset woman was strangled to death by a serving officer in 2020.

Survivors are dying as a result of police indifference to sexual violence and a systematic refusal to thoroughly investigate abuse within communities as well as in their own ranks. These failures cannot be allowed to continue.

The routine negligence and discrimination that met Gaia and meets so many survivors who report to the police – including many of those who tried to report Wayne Couzen’s past abuses – has been normalised to the point of routine. But if the police had really listened to survivors’ accounts, both Sarah and Gaia might still be with us today.

This is why since 2022 I have been campaigning for the “Gaia Principle”, which would compel officers to “join the dots” between any similar allegations against the same suspect, rather than treating them in isolation. This would improve the investigation of serious sexual abuse and help ensure that survivors of harassment and abuse can no longer be so easily denied justice or left in danger by police who cannot or choose not to investigate properly. By legislating that such negligence is a professional standards and ultimately a misconduct issue, the Gaia Principle offers a mechanism for survivors and their advocates to hold police officers to account. Put simply, an officer who cannot or will not do their job might lose their job.

There is already guidance in place that, if followed in full, would vastly improve the police investigation of sexual assault. Following years of campaigning by survivors and allies, the College of Policing’s new National Operating Model for Violence Against Women presented a detailed blueprint of how officers should safeguard survivors and conduct an thorough investigation. For example, it tells officers to be “suspect focused” in their investigations, and focus on “the behaviour of the suspect to see whether they have committed a crime, not the victim’s character”.

The fact is however that in the absence of accountability mechanisms like the Gaia Principle, these are all just words on paper. Many officers at the inquest into Gaia’s death testified that they had not read or even heard of the guidance they were supposed to be following.

The problem of British policing, the reason why women like Gaia and Sarah keep needlessly dying, is not a few rotten apples and incompetent officers but systemic misogyny, institutional indifference to sexual violence and patriarchal attitudes that enable officers to turn a blind eye to serial offenders and revictimise survivors with their subpar investigations.

Because if there are no consequences either way, guidance on issues that are not a priority will not be prioritised. And the truth is that neither for our institutionally misogynistic police nor for the patriarchal state it serves has the harassment, rape, abuse, neglect and murder of women and girls ever been a priority.

If we want to see change in our lifetime, we must make sure that Angiolini’s findings are understood not as one rotten apple slipping into the barrel or one toxic London police force in an otherwise functional system, but instead as the consequence of patriarchal culture within the police and the state as a whole that is so deeply rooted that it has completely normalised the routine dismissal and disbelief of survivors while actively sheltering perpetrators within its own ranks.

The Gaia Principle is now being considered in Parliament, having been tabled as an amendment to the Criminal Justice Bill. The modicum of basic accountability it offers in a bill that otherwise leaves police power practically unchecked is absolutely essential at this point when the time to trust the police to police themselves has so clearly passed.

It represents one step on a long road. Ultimately, we must go on to move public debate beyond the “one rotten apple” narrative that has excused so many abuses of power. It is this same narrative which normalises the institutional homophobia, ableism and racism which contributes to so many preventable deaths in custody or following police contact. We must pull up the whole rotten tree, roots and all.