The mysterious black fungus from Chernobyl that may eat radiation

Mould found at the site of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster appears to be feeding off the radiation. Could we use it to shield space travellers from cosmic rays?

In May 1997, Nelli Zhdanova entered one of the most radioactive places on Earth – the abandoned ruins of Chernobyl’s exploded nuclear power plant – and saw that she wasn’t alone.

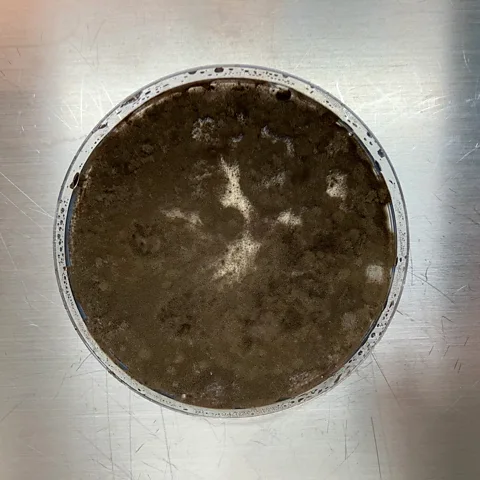

Across the ceiling, walls and inside metal conduits that protect electrical cables, black mould had taken up residence in a place that was once thought to be detrimental to life.

In the fields and forest outside, wolves and wild boar had rebounded in the absence of humans. But even today there are hotspots where staggering levels of radiation can be found due to material thrown out from the reactor when it exploded.

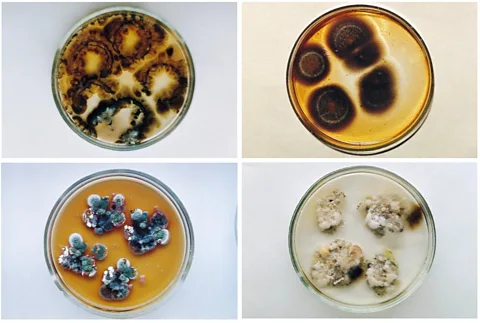

Like plants reaching for sunlight, Zhdanova’s research indicated that the fungal hyphae of the black mould seemed attracted to ionising radiation

The mould – formed from a number of different fungi – seemed to be doing something remarkable. It hadn’t just moved in because workers at the plant had left. Instead, Zhdanova had found in previous surveys of soil around Chernobyl that the fungi were actually growing towards the radioactive particles that littered the area. Now, she found that they had reached into the original source of the radiation, the rooms within the exploded reactor building.

With each survey taking her close to harmful radiation, Zhdanova’s work has also overturned our ideas about how radiation impacts life on Earth. Now her discovery offers hope of cleaning up radioactive sites and even provide ways of protecting astronauts from harmful radiation as they travel into space.

Eleven years before Zhdanova’s visit, a routine safety test of reactor four at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant had quickly turned into the world’s worst nuclear accident. A series of errors both in the design of the reactor and its operation led to a huge explosion in the early hours of 26 April 1986. The result was a single, massive release of radionuclides. Radioactive iodine was a leading cause of death in the first days and weeks, and, later, of cancer.

In an attempt to reduce the risk of radiation poisoning and long-term health complications, a 30km (19 mile) exclusion zone – also known as the “zone of alienation” – was established to keep people at a distance from the worst of the radioactive remains of reactor four.

But while humans were kept away, Zhdanova’s black mould had slowly colonised the area.

Like plants reaching for sunlight, Zhdanova’s research indicated that the fungal hyphae of the black mould seemed attracted to ionising radiation. But “radiotropism”, as Zhdanova called it, was a paradox: ionising radiation is generally far more powerful than sunlight, a barrage of radioactive particles that shreds through DNA and proteins like bullets puncture flesh. The damage it causes can trigger harmful mutations, destroy cells and kill organisms.

Along with the apparently radiotropic fungi, Zhdanova’s surveys found 36 other species of ordinary, but distantly related, fungi growing around Chernobyl. Over the next two decades, her pioneering work on the radiotropic fungi she identified would reach far outside of Ukraine. It would add to knowledge of a potentially new foundation of life on Earth – one that thrives on radiation rather than sunlight. And it would lead scientists at Nasa to consider surrounding their astronauts in walls of fungi for a durable form of life support.

At the centre of this story is a pigment found widely in life on Earth: melanin. This molecule, which can range from black to reddish brown, is what leads to different skin and hair colours in people. But it is also the reason why the various species of mould growing in Chernobyl were black. Their cell walls were packed with melanin.

Just as darker skin protects our cells from ultraviolet (UV) radiation, Zhdanova suspected that the melanin of these fungi was acting as a shield against ionising radiation.

Just as those black moulds colonised an abandoned world at Chernobyl, perhaps they could one day protect our first steps on new worlds elsewhere in the Solar System

It wasn’t just fungi that were harnessing melanin’s protective properties. In the ponds around Chernobyl, frogs with higher concentrations of melanin in their cells, and so darker in colour, were better able to survive and reproduce, slowly turning the local population living there black.

In warfare, a shield might protect a soldier from an arrow by deflecting the projectile away from their body. But melanin doesn’t work like this. It isn’t a hard or smooth surface. The radiation – whether UV or radioactive particles – is swallowed by its disordered structure, its energy dissipated rather than deflected. Melanin is also an antioxidant, a molecule that can turn the reactive ions that radiation produces in biological matter and return them to a stable state.

In 2007, Ekaterina Dadachova, a nuclear scientist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, added to Zhdanova’s work on Chernobyl’s fungi, revealing that their growth wasn’t just directional (radiotropic) but actually increased in the presence of radiation. Melanised fungi, just like those inside Chernobyl’s reactor, grew 10% faster in the presence of radioactive Caesium compared to the same fungi cultured without radiation, she found. Dadachova and her team also found that the melanised fungi that were irradiated appeared to be using the energy to help drive its metabolism. In other words, they were using it to grow.

Zhdanova had suggested that these fungi could be harnessing the energy from radiation, and now Dadachova’s research appeared to be building on this. These fungi weren’t just growing towards radiation for warmth or some unknown reaction between radiation and its surroundings as Zhdanova had suggested. Dadachova believed the fungi were actively feeding on the radiation’s energy. She called this process “radiosynthesis”. And melanin was central to the theory.

“The energy of ionising radiation is around one million times higher than the energy of white light, which is used in photosynthesis,” says Dadachova. “So you need a pretty powerful energy transducer, and this is what we think melanin is capable of doing – to transduce [ionising radiation] into usable levels of energy.”

Radiosynthesis is still just a theory, as it can only be proven if the precise mechanism between melanin and metabolism is discovered. Scientists would need to find the exact receptor – or a particular nook in melanin’s convoluted structure – that is involved in converting radiation into energy for growth.

In more recent years, Dadachova and her colleagues have started to identify some of the pathways and proteins that might underlie the fungi’s increase in growth with ionising radiation.

Not all melanised fungi show a tendency for radiotropism and positive growth in the presence of radiation. A 2006 study from Zhdanova and her colleagues, for example, found that only nine of the 47 species of melanised fungi they collected at Chernobyl grew towards a source of radioactive caesium (caesium-137).

Similarly, in 2022, scientists at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico found no difference in growth when two species of fungi (one melanised, one not) were exposed to UV radiation and caesium-137.

But that same year, the same tendency for fungal growth when exposed to radiation was found again – in space.

Different from the radioactive decay found at Chernobyl, so-called galactic cosmic radiation is an invisible storm of charged protons, each travelling near the speed of light through the Universe. Originating from exploding stars outside our solar system, it even passes through lead without much trouble. On Earth, our atmosphere largely protects us from it but for astronauts travelling into deep-space it has been called “the greatest hazard” to their health.

But even galactic cosmic radiation was no problem for samples of Cladosporium sphaerospermum, the same strain that Zhdanova found growing throughout Chernobyl, according to a study that sent these fungi to the International Space Station in December 2018.

“What we showed is that it grows better in space,” says Nils Averesch, a biochemist working at the University of Florida and co-author of the study.

Compared to control samples back on Earth, the researchers found that fungi that faced the galactic cosmic radiation for 26 days grew an average 1.21 times faster.

Even so, Averesch is still unconvinced that this is because C. sphaerospermum was harnessing the radiation in space. The increased levels of growth could also have been the result of zero gravity, he says, another factor that fungi back on Earth didn’t experience. “Averesch is now conducting experiments using a random positioning machine that simulates zero gravity here on Earth to parse these two possibilities.

But Averesch and his colleagues also tested the protective potential of the melanin in C. sphaerospermum by putting a sensor underneath a sample of the fungi aboard the International Space Station. Compared to samples without fungi, the amount of radiation blocked increased as the fungi grew, and even a smear of mould in a petri dish seemed to be an effective shield.

“Considering the comparatively thin layer of biomass, this may indicate a profound ability of C. sphaerospermum to absorb space radiation in the measured spectrum,” the researchers wrote.

Averesch says it’s still possible the apparent radioprotective benefits of fungi are due to components of biological life other than melanin. Water, for example, a molecule with a high number of protons in its structure (eight in oxygen and one in each hydrogen), is one of the best ways to protect against the protons that zoom through space, an astrobiological equivalent of fighting fire with fire.

Even so, the findings have opened intriguing prospects for solving a problem of space-based living. Both China and the US plan to have a base on the Moon in the coming decades, while Texas-based SpaceX aims to have its first mission to Mars blast off by the end of 2026, and land humans there three to five years later. Any people living on these bases will need to be protected from cosmic radiation. But using water or polyethylene plastic as a radioprotective cocoon for these bases might be far too heavy for liftoff.

Metal and glass present a similar problem. Lynn J Rothschild, an astrobiologist at Nasa’s Ames Research Centre, has likened transporting these materials into space to build space bases to a turtle carrying its shell everywhere it goes. “[It’s] a reliable plan, but with huge energy costs,” she said in a 2020 Nasa release.

Her research has led to fungal based furniture and walls that could be grown on the Moon or Mars. Not only would such “myco-architecture” reduce the cost of lift-off, but – if the findings from Dadachova and Averesch prove correct – it could also be used to form a radiation shield, a self-regenerating barrier between the space-faring humans and the storm of galactic cosmic radiation outside.

Just as those black moulds colonised an abandoned world at Chernobyl, perhaps they could one day protect our first steps on new worlds elsewhere in the Solar System.