‘The most desolate place in the world’: The sea of ice that inspired Frankenstein

This French glacier has given rise to countless works of art in the past 200 years, including Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Paintings, photographs and modern satellites reveal how the site has dramatically transformed since Shelley was first transfixed by it.

In the 1800s, above the town of the Chamonix in the French Alps, there was a sublime sight known as the “sea of ice” that provoked both awe and a touch of dread. Those who climbed up the mountain trails to see it would encounter an icy, barren expanse of white, dark blue and aquamarine. Visitors described a scene akin to a torrent of waves and whirlpools frozen in time; an unrelenting frost extending boundlessly into the mountains.

Many artists at the time painted this icy sea, but one of the most striking images is an early photograph: a gloomy daguerreotype taken by an assistant of the writer John Ruskin in the 1850s (above).

This was the “Mer de Glace” glacier – a mass of compacted snowfall, creeping down from the Mont Blanc massif. For centuries, it has remained the largest glacier in France, and was one of the first to be studied scientifically.

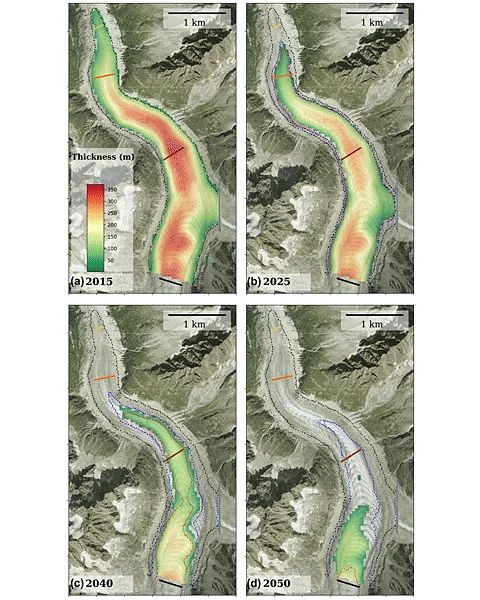

Sadly, it has shrunk profoundly since then – more than 2.5km (1.6 miles) since the mid-1800s – and as I discovered following a recent visit, it is barely visible from the same point that the Ruskin photo was taken. The melting is accelerating, and by 2050, scientists anticipate it could retreat by at least 2km (1.2 miles) further, even with stringent emissions reductions.

Unlike many glacier retreats around the world tracked via remote sensing or ground measurements, the Mer de Glace is unusual because its changes have been captured in painting, photography and literature. Over the centuries, many writers and artists have come to feel overwhelmed by its scale.

And among the most notable was a young Mary Shelley. In 1816, the writer had yet to publish Frankenstein – the book she’d later call her “hideous progeny” (most recently adapted into a film directed by Guillermo del Toro). But her hike to the glacier would prove to be a major influence, providing her with the setting for a pivotal scene between Viktor Frankenstein and the creature.

By comparing Mary and her contemporaries’ descriptions with paintings and photography across the years, it’s possible to see how this once-stunning sea of ice has transformed.

In the 1800s, the Mer de Glace was so big that it almost nosed into settlements in the Chamonix valley below, as this painting from the 1820s shows:

Samuel Birmann

Samuel BirmannAround this period, taking the “Grand Tour” across Europe was fashionable, which meant many artists and writers passed through the Alps en route to Italy.

After Charles Dickens visited in 1847, he wrote how the glacier and other sights of Chamonix “are above and beyond one’s wildest expectation. I cannot imagine anything in nature more stupendous or sublime. If I were to write about it now, I should quite rave – such prodigious impressions are rampant within me.”

This is how the artist JMW Turner painted the Mer de Glace when he came in 1802:

Alamy

AlamyAnd in 1826, a Swiss artist composed this scene from roughly the same point as the Ruskin daguerrotype, looking south-east from the Refuge du Montenvers hotel:

Samuel Birmann/ Swiss National Library

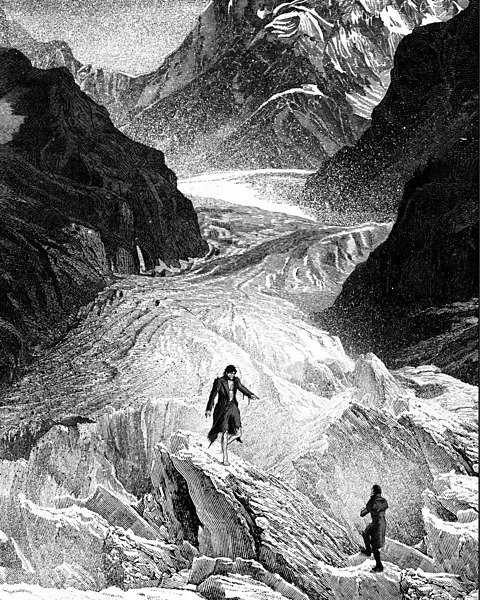

Samuel Birmann/ Swiss National LibraryWhen 18-year-old Shelley – then Wollstonecraft Godwin – visited, the icy sea would make a deep impression. In 1816, the so-called “Year Without Summer”, she travelled up to the glacier with her stepsister Claire Clairemont and soon-to-be husband Percy Shelley, the poet.

Setting off on horseback, the trio navigated a vertiginous path with pine trees and snowy hollows. At one point, a mule slipped and they almost fell into the valley. As they ascended, the scenery became ever more barren and dreadful, until they eventually reached Montenvers, where they could walk onto the glacier.

“This is the most desolate place in the world – iced mountains surround it – no sign of vegetation except on the place where we view the scene,” Shelley wrote in her diary. “It is traversed with irregular crevices whose sides of ice appear blue while the surface is of a dirty white.”

Her partner Percy was similarly struck. Later, he recalled “a scene in truth of dizzying wonder”. And his description of the glacier captured why it had been named a “sea”: “The vale itself is filled with a mass of undulating ice,” he wrote. “It exhibits an appearance as if frost had suddenly bound up the waves and whirlpools of a mighty torrent…The waves are elevated about 12 or 15ft (4 or 5m) from the surface of the mass, which is intersected by long gaps of unfathomable depth, the ice of whose sides is more beautifully azure than the sky.”

The trip would later inspire the couple’s literary writing. For Percy, the Alpine landscape would feed into his much-studied 1816 poem Mont Blanc. And in one scene in Frankenstein, Mary would place her characters upon the icy ocean’s surface.

In Chapter 10 of the 1818 edition, Victor Frankenstein visits Chamonix in search of solace. Struck by guilt following the creature’s murder of his brother – as well as the unjust execution of the girl blamed – the scientist climbs to the Mer de Glace in the hope that “the awful and majestic in nature” might salve his woes. Hiking across it, he describes the glacier as “rising like the waves of a troubled sea, descending low, and interspersed by rifts that sink deep”. However, a moment later, his solace is punctured when he sees the creature bounding towards him across the ice for a confrontation.

John Coulthart

John Coulthart Elsie Russell

Elsie RussellIn the summer of 2023, I visited the Mer de Glace while researching the Shelleys for a writing project, in the hopes of seeing the glacier for myself. I arrived in Chamonix mid-afternoon, too late to catch a ticket for the train that now transports tourists. So, I hiked the steep path instead, up through a forested valley where fountains of glacial meltwater streamed down from the peaks.

The valley that once held a roiling ocean of crevasses is now bare, apart from powdery moraine and the trickle of meltwater

Two hours later, I arrived at Montenvers – where the Shelleys had their lunch and Ruskin’s assistant took his daguerrotype. I looked out into the valley, hoping for a hint of the unrelenting frost. But there was no sea. Instead, all I saw was an absence. I knew beforehand that the glacier had retreated due to climate change, but it was shocking to discover just how much. The valley that once held a roiling ocean of crevasses is now bare, apart from powdery moraine and the trickle of meltwater. The glacier is there, but it has almost fully recoiled out of view behind the curve of the mountainside in the distance.

Later, I tried to piece together the glacier’s retreat using images taken from the same Montenvers viewpoint. As little as 100 years ago, it was still an icy sea. Here is how it looked in 1926:

Alamy

AlamyHowever, by the start of the 21st Century, it sat far lower in the valley, with fewer crevasses and a coating of powdery moraine. In 2002, the retreat began to accelerate. Here is the glacier in 2014:

Guilhem Vellut

Guilhem VellutIn 2018, the artist Emma Stibbon made the following cyanotype. Having seen the Ruskin daguerreotype (at the top of this article), she wanted to produce an image that echoed the style – and show how much it had changed since then. (She also contributed to a radio documentary, aiming to paint some of the same landscapes that Turner depicted when he visited.)

Emma Stibbon

Emma StibbonAnd finally, here is how it looked when I visited in summer 2023, following the particularly hot summer in 2022 when there was record ice loss from glaciers across the Alps:

Richard Fisher

Richard FisherToday, the glacier has retreated so far that you need to take a cable car, installed in 2024, down into the valley if you want to see it up close.

Scientists have modelled the glacier’s extent over the next century. With climate change causing hotter summers, they anticipate it could retreat by a further 2km (1.2 miles) by 2050, even with stringent emissions reductions. That’s roughly the same distance it shrunk between Shelley’s visit in the 1800s and the turn of the 21st Century. In the worst-case scenario models, it disappears entirely by 2099 (but fortunately that emissions pathway is now considered unlikely.)

When Frankenstein arrives at Mer de Glace in Mary Shelley’s novel, ruing the creature he created, he describes a sublime, uplifting scene that the writer herself would have encountered in 1816:

“The sea, or rather the vast river of ice, wound among its dependent mountains, whose aerial summits hung over its recesses,” he narrates. “Their icy and glittering peaks shone in the sunlight over the clouds. My heart, which was before sorrowful, now swelled with something like joy.”

Yet if Mary were alive to encounter the glacier today, she would see something quite different: the impact of climate change on France’s largest glacier. No sea of ice, but instead a landscape that is monstrously man-made.