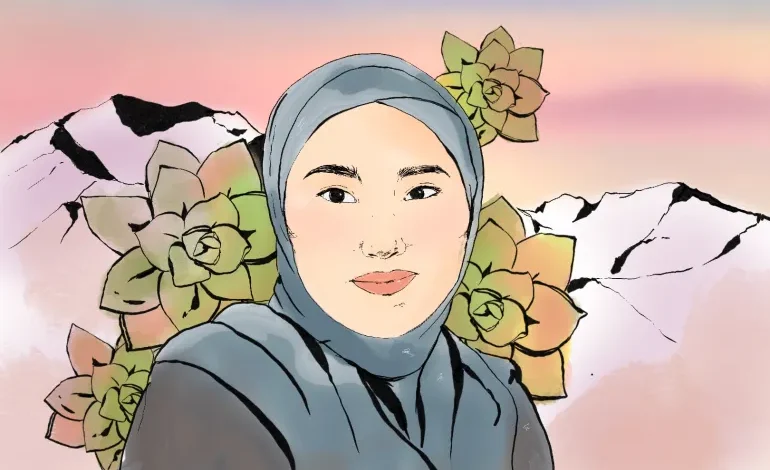

The girl with sun-shaped earrings: A family remembers a murdered daughter

When Mediyana Talantbekova was about 10 years old, she would watch over her family’s calves. One day, one of them went to graze in a field of clover, a plant that can cause deadly bloating, and died.

Mediyana, who lived with her family in Osh, a city in southwestern Kyrgyzstan, was distressed by the calf’s death and felt she was to blame.

When her father, Talantbek Ergeshov, a farmer, returned home that evening he found her sitting quietly in a corner of the house. “What’s wrong, my daughter? You seem upset,” he recalled asking her.

Mediyana started crying. “Dad, I killed a calf,” she told him.Talantbek comforted his daughter. “Aw my girl, don’t cry, it’s not such a problem,” he told her. He helped her understand that the calf’s death was not her fault and, to cheer her up, he told her he would take her to the bazaar the following morning to buy a pair of earrings.

That night, Mediyana got out of bed and went to wake her father. “Daddy, the sun is not rising,” she told him, impatient for the day to begin.

When morning came, Talantbek took his daughter to the gold bazaar to get her ears pierced. He then bought her a pair of earrings shaped like suns. He remembers how happy Mediyana was and how she told him: “Dad, from now on I will watch the calves so none of them dies.”

Twelve years later, on a winter’s day in January, Mediyana, a 22-year-old student, would fail to turn up for her dentistry exam. Her friends, family and the police would search for her for nine days until her body was discovered in the back yard of a house in Osh. Talantbek would go to the morgue to identify his only daughter, the sun-shaped jewellery still in her ears.

Mediyana was murdered by a classmate who, just a few weeks earlier, had drugged and raped her. The shame and stigma associated with rape, even more so in a deeply conservative society like Kyrgyzstan, meant Mediyana initially didn’t tell anyone. Instead, she felt compelled to “negotiate” a marriage to her rapist to secure a future where she could raise her unborn child.

‘She loved this house’

On a sunny day in early September 2022, Talantbek, 47, a small, solidly built man, dressed in a plain white T-shirt and lightweight grey pants, stood in front of the one-storey yellow brick house in central Osh where he had lived with Mediyana.

“She loved this house. While we lived here my daughter tried to do everything to make it cosy,” he said, describing how Mediyana had decorated the place with potted flowers, cactuses and succulents.

When it was warm, Mediyana and Talantbek would sit on the front porch on “toshoks”, colourful, burgundy-hued patchwork mattresses, drinking tea and talking about their day.

“She was always a very kind and smiley kid — very friendly,” Talantbek said.

Mediyana spent almost all her life in Osh – Kyrgyzstan’s second-largest city after the capital Bishkek – which lies close to the Uzbekistan border.

The city, which grew out of a settlement along ancient Silk Road trade routes, is known for the low-lying Sulaiman-Too Sacred Mountain, which has long attracted Muslim pilgrims and is one of three Krygyz UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Simple one-storey houses line narrow streets in the centre of the city of 300,000, while traditional eateries serve samsa, lamb or mutton pastries baked in clay ovens, and the bazaars are crowded and noisy.

In 2023, about 14 percent of Osh’s population lived below the poverty line, earning an average of $2 a day. Since the early 2000s, residents from Osh, and elsewhere in the cou

Potato pies and late-night studies

Mediyana’s family was no exception.

In 2011, her mother, Gulmayram, stopped working on the family farm to join her sister in the Russian capital to save money to build a new house. Later that year, Talantbek, Mediyana, then 11, and her younger brother, Adilet, then 9, joined her.

But the children didn’t like Moscow and returned to Osh to live with their relatives. They would visit their parents during the school holidays, and Mediyana would text and video call daily with Gulmayram, who still lives there, working as a cashier in a bakery.

Adilet moved to Moscow when he was 18 and found a job in a travel agency. Talantbek, who worked there as a security guard, returned to Osh in 2018 and lived with Mediyana while building a new two-storey family home in the quiet suburbs, growing apples and breeding horses.

, have migrated to Russia in search of better work opportunities.