‘The fate of nations and the fall of kingdoms’: History’s epic theories of what causes aurora

From creation myths to political omens, different cultures have had vastly different interpretations of the dramatic natural phenomenon.

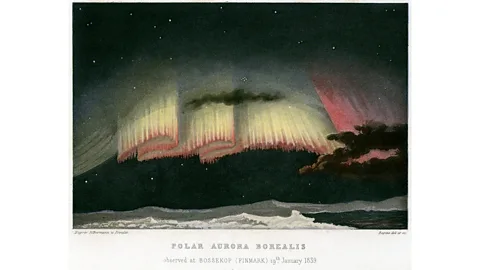

In the days after a Jacobite uprising was quashed in England in 1716, strange lights were seen streaking across the night skies.

They were variously described as looking like “pure flame”, “something resembling the pipes of an organ”, and a “shower of blood”. People also had different interpretations of what they were seeing, from giants with flaming swords to armies fighting in the sky.

During the Jacobite Rebellion, the deposed Catholic Stuarts sought to regain the English throne from the Protestant monarchy, and the interpretation of these visions depended on an individual’s political and religious leanings. As one English clergyman and writer wrote at the time, some viewed the “portentous stranger” with anxious amazement. Others, he added, “read, in its glaring visage, the fate of nations, and the fall of kingdoms”.

In Finnish Lapland, the Northern Lights were the flick of an arctic fox’s tail through a snowdrift, a story still embedded in their Finnish name ‘revontulet (fire fox)’

Today we know that the playful displays of colour and shape from the aurora borealis are caused by activity on the surface of the Sun. These light up the skies beyond its usual haunts when solar activity spikes. In recent days, a strong geomagnetic storm has made the northern lights visible in many areas of the UK and the US.

But written records and oral traditions show that people have been fascinated by these dancing colours for millennia – and have come up with some intriguing theories of what was causing them.

Some of these stories are relics of the past. Norse cosmology’s Bifröst, the rainbow ridge that connected the land of mortals with the realm of the gods, for example, may have been a reference to the aurora.

But others remain part of oral storytelling traditions, typically viewed as cultural heritage or moral teaching rather than literal belief.

‘Burning flame’

Until a few decades ago, the earliest reference to aurora was thought to be from China from 193 BCE, when an emperor of the Western Jin dynasty wrote that “the sky opened in the north east”.

But scholars are now finding even older possible references. Ancient Greek texts, for example, such as Aristotle’s Meteorologica from around 330 BCE, may be referring to aurora. This describes night-time visions that sometimes take on the “appearance of a burning flame, sometimes that of moving torches and stars”.

There’s also the mention of a “very red rainbow stretched in the east” contained within astronomical diaries on clay tablets from Babylonia from 567 BCE, as well as Assyrian records that predate it by at least a century. Assyrian scholars carved these references to “red glow”, “red cloud” and “red sky” on ancient cuneiform tablets alongside an interpretation of what they represented – such as omens for historical events – to inform their kings.

But the known oldest reference may now be a 3,000-year-old text written some 300 years earlier on bamboo slips. In a 2023 paper, researchers identified a mention of aurora in The Bamboo Annals, a chronicle of ancient China. It describes a “five-coloured” event occurring during the night, which the researchers say indicates a “possible extreme space weather event” in the early 10th Century BCE.

Researchers can make educated guesses that these poetic descriptions were of aurora by cross-referencing historical accounts with scientific data like past solar activity and the position of Earth’s shifting magnetic field, and by ruling out other celestial phenomena.

Fire, blood and death

These examples are noteworthy because they provide evidence from places where the aurora is seldom seen. But for people living at high latitudes – Iceland, Greenland, northern Scandinavia, Alaska, Canada, and northern Russia – the Northern Lights are a regular occurrence. Here, aurora have long been a part of a broader worldview connecting people and their environment.

Traditions vary widely between different communities, from creation myths to navigation and weather predictions. For some the Northern Lights represent ancestors or shamanic powers.

“Indigenous peoples throughout the Arctic area combine their spiritual understanding of the Northern Lights with their physical relationship to them, often through stories,” wrote Mel Olsen and Faith Fjeld, who are both involved in a North American Sami reawakening, in a 2020 article.

Death and struggle are common themes. The aurora certainly inspired fear in some Sami communities, write Olsen and Fjeld. Their appearance would prompt warnings to be quiet when the aurora shone – and certainly not to tease it – and advice to women to cover their hair to avoid becoming entangled in its rays.

Similar warnings are still shared among Alaska’s Indigenous people today, some of whom say they were told stories as children of the Northern Lights playing football with their heads to frighten them into coming home on time.

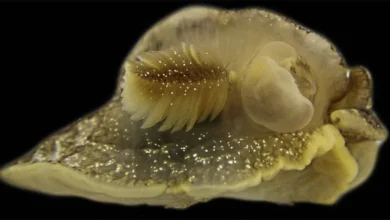

Meanwhile, the full majesty of the southern lights – the aurora australis – is largely seen only by penguins, but it is still sometimes visible to people who live very far south. Interpretations of aurora in First Nations traditions are often associated with blood, fire and death.

“Aurorae cause great fear in the people who witness them and in some communities they are taboo – only to be viewed and interpreted by initiated elders,” researcher Duane Hamacher, now a professor of cultural astronomy at The University of Melbourne in Australia, wrote in 2013.

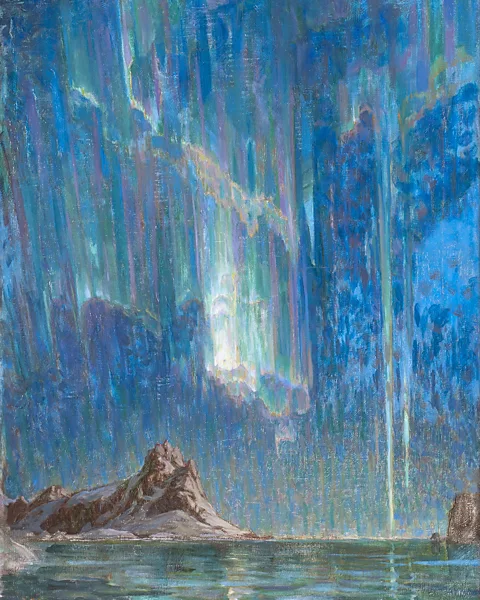

Shimmering dancers

Despite the breadth of historical allusions, the modern name of aurora borealis was not coined until the 17th Century. The first known recorded references come from Italian astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei in his 1619 work Discourse on the Comets, where he referenced Aurora, the goddess of dawn in Roman mythology, and Boreas, the Greek god of storms and the North wind. Its southerly counterpart, aurora australis, is named after Auster, the Roman god of the South wind.

Other names for the phenomenon give hints about how they are perceived. In Finnish Lapland, the Northern Lights were the flick of an arctic fox’s tail through a snowdrift, a story still embedded in their Finnish name revontulet (“fox fires”). In Shetland dialect they are the joyful mirrie dancers (“mirr” means “to shimmer”).

Meanwhile, the Sami word guovsahasat translates to “the lights you can hear”, says Fiona Amery, research fellow in history and philosophy of science at the University of Cambridge in the UK. This is a reference to the strange sounds people report occasionally experiencing alongside the aurora’s visual effects. “For [these people], the sound and the visuals are completely intertwined.”

In places where strange lights only occasionally appeared in the sky, people often had different responses to those in areas where they were a more regular occurrence. At times people would read deep political and religious significance into the appearance of aurora.

During the American war of independence in the 1700s, for example, Welsh poet Hugh Jones, interpreted auroral sightings as a sign that Britain should uphold the Protestant faith and make peace with America.

Nationalmuseum Sweden

Nationalmuseum SwedenAfter the 1716 sightings during the Jacobite Rebellion, astronomer Edmund Halley (after whom the famous comet was named) described the “surprising appearance” of these lights and tried to explain their scientific provenance. Still, when sightings of the aurora also coincided with the final rising in 1745, the visions of lights in the north were again interpreted as divine, with another Welsh poet describing them as arwyddion cryfion Crist (Christ’s strong signs).

These examples show how people would particularly project spiritual or political significance onto a natural event like the aurora during periods of upheaval or uncertainty, says Cathryn Charnell-White, a researcher in Welsh and Celtic studies at Aberystwyth University in Wales.

From stories to science

As fantastical as some of these stories are to the modern reader, they give us an insight into cultural attitudes towards natural phenomena. Auroral histories also illuminate the gradual process by which people learned how they work.

The sounds of the aurora, for example, were long considered a psychological phenomenon, says Amery, but once researchers began to better value the experiences of people living in northern territories they began to theorise that they are caused by the release of static charge.

Some histories are also helping scientists develop a more accurate understanding of the solar cycle and associated geomagnetic storms that can disrupt modern communications and navigation equipment.

Robert Marc Friedman, emeritus professor in the history of science at the University of Oslo in Norway, points out that there are still plenty of modern myths floating around about this completely natural phenomenon. One, he says, is that Japanese tourists travel to Scandinavia to have sex under the Northern Lights in the hope of conceiving a lucky child. The story may have been deliberately fabricated, but the idea is still being endorsed by canny tourism operators, so may have become self-fulfilling.