Sycamore Gap: New life springs from rescued tree

New life has sprung from the rescued seeds and twigs of the Sycamore Gap tree mysteriously cut down last year, giving hope that the iconic tree has a future.

Millions once visited the sycamore tree nestled in a gap in Hadrian’s Wall.

A national outpouring of shock and dismay followed its felling in September.

Police are still investigating what happened in what they call a “deliberate act of vandalism”. Two men remain on bail.

Just a stump is now left – if it is healthy, a new tree could eventually grow there.

Young twigs and seeds thrown to the ground when the tree toppled were salvaged by the National Trust, which cares for the site with the Northumberland National Park Authority.

When we inquired about what happened to those specimens, they invited us to see for ourselves.

We can’t disclose the exact location of the high security greenhouse, except that it is somewhere in Devon.

It guards genetic copies of some of the UK’s most valuable plants and trees.

Its hall of fame includes copies of the apple tree that Sir Isaac Newton said inspired his theories on gravity, and a 2,500-year-old yew that witnessed King Henry VIII’s relationship with Anne Boleyn in the 1530s.

These are back-up plants – insuring the nation’s heritage in case of an outbreak of disease, a devastating storm, or an attack on the trees.

No-one expected the sudden loss of the Sycamore Gap tree, once one of the most photographed spots in Britain.

Now the green shoots poking through large pots of soil give promise it will live on.

The National Trust is still deciding what to do with them once they are strong enough – schools and communities could be given saplings to grow their own Sycamore Gap tree, explains Andy Jasper, director of gardens and parklands. If the stump does not regrow, one might replace it.

But for now, the priority is nurturing the tiny shoots.

Before entering the greenhouses, we must walk through disinfectant to stop diseases contaminating the site. The blue plastic covers put on our shoes will be incinerated when we leave.

In September it was a race against time to get the seeds and living twigs to this special centre.

“As soon as you cut something down it’s dying,” explains Chris Trimmer who runs the nursery.

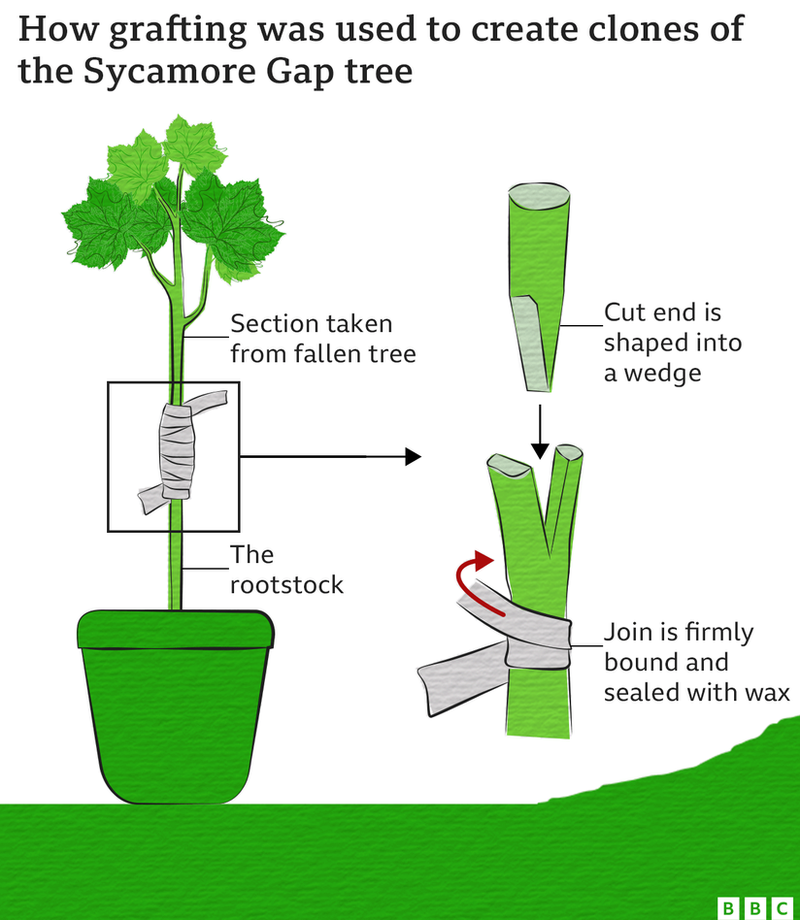

When the tree came down, local horticulturist Rachel Ryver sprang into action – climbing over the damaged tree and wall to collect what is called scion – young twigs with buds. This was vital raw material for grafting genetic copies of the tree.

“It was drying out fast – we had to save whatever we could. Hours later I was standing at Hexham post office thinking “nobody knows I’m carrying what’s left of the Sycamore Gap tree”,” Rachel says.

The five bags of twigs, seeds and a few leaves arrived in Devon at 09:30 the next day.

Chris Trimmer was waiting. He has worked with plants since he was 12 – decades later, he is one of the UK’s leading horticulturists.

For him, like many across the country, the story is personal. The first film he went to see with his now-wife was Robin Hood Prince of Thieves – its scene of Kevin Costner and Morgan Freeman at Hadrian’s Wall catapulted the tree to global fame.

Chris is softly-spoken, talking scientifically about the process. “It’s our job to graft this stuff,” he says.

He unpacked the bags, ran tests to check the material was free of disease, then bleached it for five minutes.

It was quite a moment. “If one had shown disease, it all would have been destroyed,” he says.

By 15.30 Chris was done – 20 pieces grafted. But he was lucky. Autumn is a bad time to do this work – it should be done in January when the trees are dormant. He just about got away with it.

Grafting is an old technique, used by ancient Egyptians and Romans. “It’s a bit Frankenstein-esque – adding body parts onto something else, making a hybrid. But it’s worked for hundreds of years,” explains Andy Jasper.

Using a lime tree as an example, Juliet Stubbington, a propagator who works alongside Chris, demonstrates how it was done. “You have to be confident with a knife,” she says.

Grafting binds fresh roots with living twigs that have buds of the same species. The hope is that the two knit together to make one larger living young tree. This was the only way to preserve the beloved Sycamore Gap tree. “It is the same tree,” Juliet explains.

Her work is not just technical to her. “It’s lovely to help them grow back. Each one of these trees is a story,” she says.

The horticulturalists also successfully planted seeds from the Sycamore Gap tree, now its descendants.

Five months on, they are looking after nine surviving grafted plants and 40-50 seedlings.

“This is literally the first one that came up,” Andy Jaspar says, carrying a small pot with a 10cm green shoot. People have cried when holding it, he says. It’s next to a type of rhododendron seedling that is the only known one in the world.

Juliet says the success rate should be high. Sycamores are famously hardy.

But the sense of responsibility is huge and she has to stop herself fussing over them. “The best way to kill something is to over-care for it,” she says.

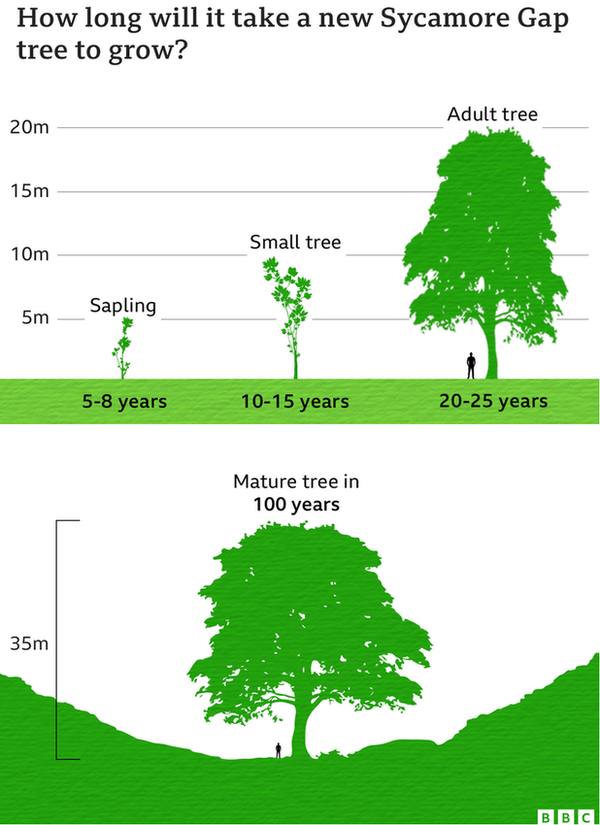

Nothing can bring back the tree exactly as it was. It was planted in the natural dip of Hadrian’s wall in the late 1800s – time and the weather moulded it into its famous silhouette.

That shape is gone but what is born from its ruins will have its own story. It will be three years before horticulturists know if the stump is healthy enough to produce the next tree.

Until then, these seedlings hundreds of miles away are primed – each one waiting to see if it could be the next Sycamore Gap tree.