Sea-level rise: West Antarctic ice shelf melt ‘unavoidable’

Increased melting of West Antarctica’s ice shelves is “unavoidable” in the coming decades, a new study has warned.

These floating tongues of ice extend from the main ice sheet into the ocean, and play a key role in holding back the glaciers behind.

But as ice shelves melt, it can mean that the ice behind speeds up, releasing more into the oceans.

The study’s findings suggest that future sea-level rise may be greater than previously assumed.

“Our findings seem to increase the likelihood that [current] estimates [of sea-level rise] will be exceeded,” Dr Kaitlin Naughten of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), the report’s lead author, said.

In 2021, the UN’s climate body, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released its latest estimates of future sea-level rise.

It projected global average sea-level rise of between 0.28m and 1.01m by 2100 – one key reason being the melting of glaciers and ice sheets.

Sea-level rises of around a metre may not sound much, but even these increases would put hundreds of millions of people worldwide at risk of coastal flooding.

However, the IPCC also noted that higher rises were possible due to “ice-sheet-related processes that are characterised by deep uncertainty” that were not directly included in its estimates.

One of these key uncertainties is how the ice sheet interacts with the oceans.

This latest study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, is the first to directly simulate how ocean warming will affect Antarctic ice shelves in response to different levels of greenhouse gas emissions. These are the gases produced when fossil fuels are burned – the main contributor to human-induced climate change.

Amundsen Sea, off the coast of West Antarctica, will warm roughly three times faster than the historical rate through the rest of this century, the study finds. This will lead to much more rapid melting of ice shelves.

Concerningly, this will still happen even if humanity takes strong steps to slow warming, the study suggests. But this is not a reason to avoid moving away from fossil fuels, Dr Naughten stresses.

“What we do now will help to slow the rate of sea-level rise in the long term,” she explains.

The authors caution that further work is needed to increase confidence in its conclusions, but the findings are significant because of how ice shelf melting affects the rest of West Antarctica.

The importance of ice shelves

The Antarctic ice sheet contains enough ice to raise global sea-levels by about 58m (190ft) if it melted entirely.

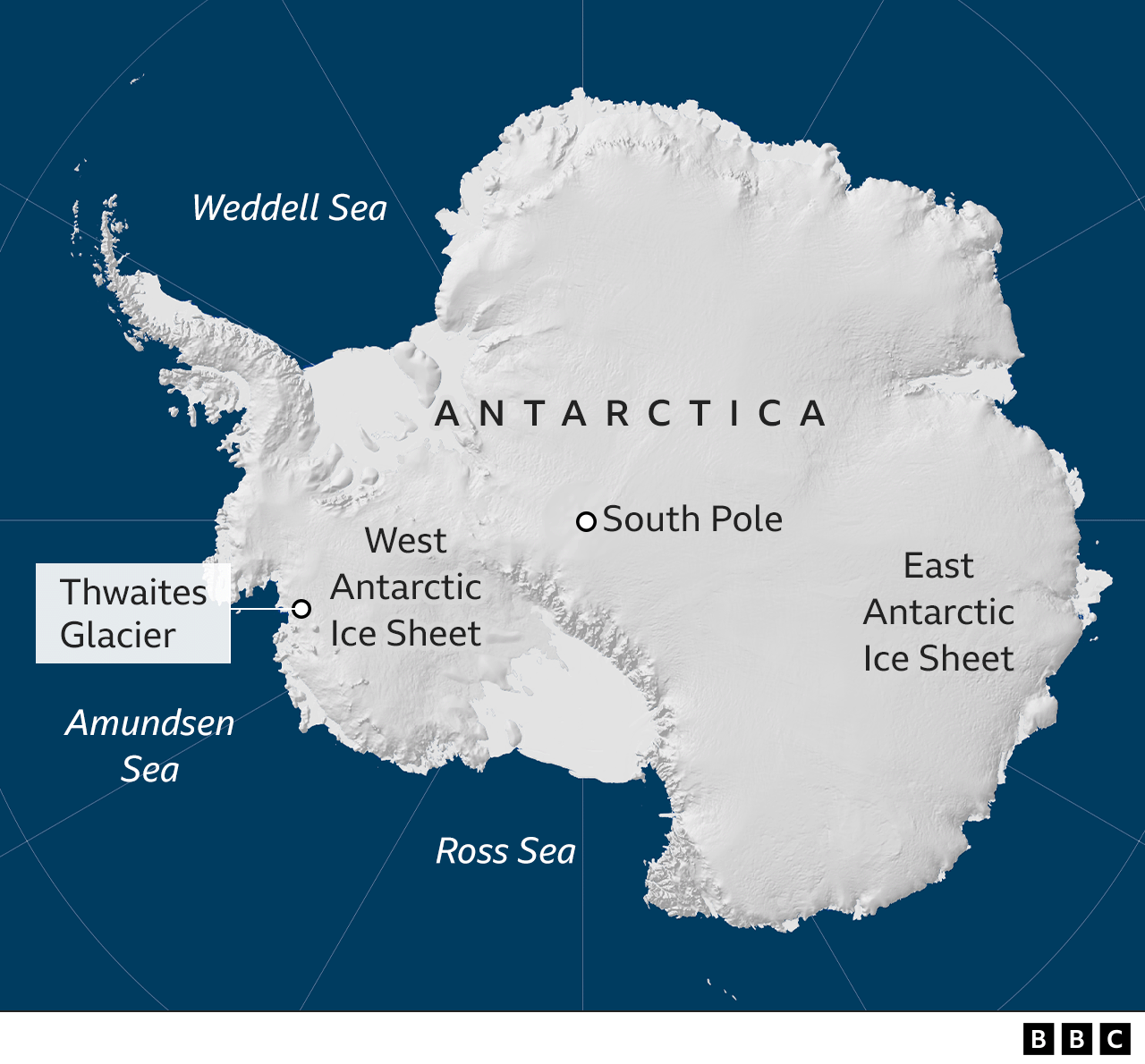

Most is held in East Antarctica, which has been relatively stable in recent years and is not expected to collapse in the near future.

But a sizeable portion – enough to raise sea-levels by around 5m (16ft) – is held in West Antarctica, which is considered less stable and has been losing mass in recent decades.

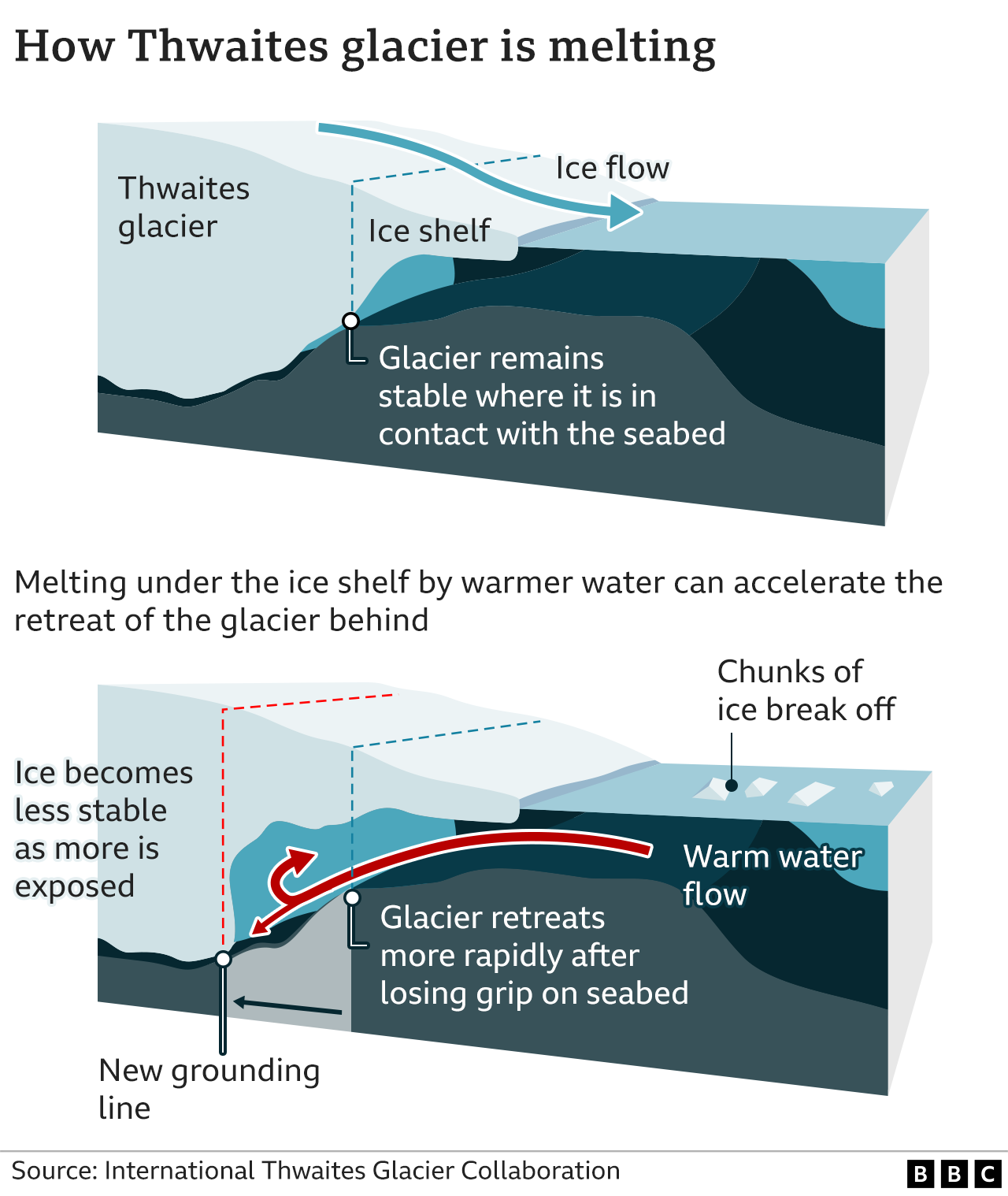

Ice grounded on the bedrock of the Antarctic continent generally flows towards the oceans. In many places, these grounded glaciers extend on to the ocean surface, where the ice floats. These are ice shelves.

They play a crucial role in holding back the mass of ice behind. But the melting of ice shelves by warm ocean waters reduces this effect. This can cause the glaciers behind to accelerate.

As it does so, more ice may enter the ocean through melting, or break off to form icebergs.

What’s more, unlike most of East Antarctica, much of the West Antarctic continent sits below sea-level. This means that glaciers may retreat into deeper and deeper waters, accelerating the loss of ice.

This is the concern with Thwaites Glacier that flows into the Amundsen Sea. Thwaites, sometimes referred to as the “doomsday glacier” because it would raise global sea-levels by around 65cm (25in) if it collapsed entirely, is highly vulnerable to warming.

Its grounding line – the point where ice loses contact with the bedrock and starts to float – is already retreating by more than 1km per year in some places.

“This study worsens the outlook for Thwaites Glacier, as we simulate rapidly increasing melting beneath its connected ice shelf,” Dr Naughten told the BBC.

The processes triggered by faster ice shelf melting “could lead to the collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet”, the authors suggest.

However, other factors will also affect how the ice sheet responds to warming, and therefore how quickly sea-levels rise, such as snowfall, surface ice melting and the speed of glacier flow. These were not directly considered in this latest study.

A ‘wake up call’

It is well-established that sea-levels will continue to rise in the coming decades and centuries.

This is because ice sheets take a long time to fully adjust to changes to the rapid warming of recent years, with further temperature rises to come.

But this latest study adds weight to the idea that sea-levels may rise faster than previously assumed as a result of increased ice shelf melt, to which societies worldwide will have to adapt.

“It looks like we’ve lost control of melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet,” concludes Dr Naughten.

“This is a sobering piece of research,” agrees Alberto Naveira Garabato, a professor in physical oceanography at the University of Southampton who was not involved in the latest work.

But researchers emphasise this is not a reason to give up.

Steps taken to slow the loss of ice, through cutting greenhouse gas emissions, could be crucial in giving societies time to prepare for and adapt to rising seas.

“It should serve as a wake up call,” Prof Naveira Garabato explains.

“We can still save the rest of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, containing about 10 times as many metres of sea-level rise, if we learn from our past inaction and start reducing greenhouse gas emissions now.”