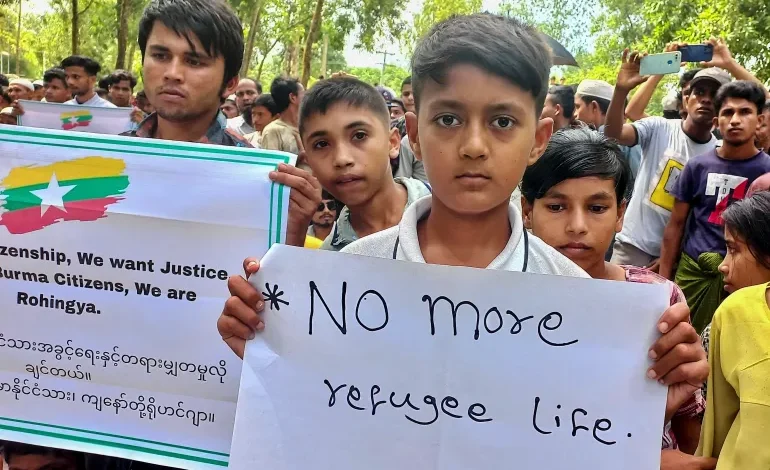

Rohingya youth long for a future beyond the barbed wire

Sadia Rahman

Sadia Rahman

Six years have now elapsed since the world watched 700,000 Rohingya flee from Myanmar to Bangladesh in search of safety. About half of them were children and young people. What was expected to be a short-term refuge has become another protracted crisis. Those who fled as children have now reached the age of adolescence; those who were teenagers are now adults.

Like most children, they aspire to become doctors, engineers, teachers, sports stars, and artists – a stark contrast to their reality. Living in the world’s biggest refugee camp, surrounded by barbed-wire fences, Rohingya refugees are blocked from accessing formal education, earning an income, and moving freely through or beyond the camp.In such conditions, what hope they can have to build the kind of future they dream of? There should be scope for them to improve their lives, be it through education or paid work.

Many of the young Rohingya I have met as part of my work at these camps tell me they feel forgotten by the world. They tell me the barriers between them and the life they want for themselves engulf them with a sense of despair. They say their voices go unheard and that they have lost the right to dream. This sense of helplessness has a visceral impact on their mental health.

A 2022 survey of 317 refugee youth and adolescents across 11 camps conducted by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) found that 96 percent of the respondents were unemployed and that they constantly feel anxious and stressed.

Amin is a young Rohingya I know well. Six years ago, he was a high-school student in his home country. He planned to go to university and become a lawyer. Then one day, his village was burned down, and his relatives were killed before his eyes. Scared for their lives, he and his family walked for 10 days before crossing the border to reach safety in Bangladesh.

In such conditions, what hope they can have to build the kind of future they dream of? There should be scope for them to improve their lives, be it through education or paid work.

Many of the young Rohingya I have met as part of my work at these camps tell me they feel forgotten by the world. They tell me the barriers between them and the life they want for themselves engulf them with a sense of despair. They say their voices go unheard and that they have lost the right to dream. This sense of helplessness has a visceral impact on their mental health.

A 2022 survey of 317 refugee youth and adolescents across 11 camps conducted by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) found that 96 percent of the respondents were unemployed and that they constantly feel anxious and stressed.

Amin is a young Rohingya I know well. Six years ago, he was a high-school student in his home country. He planned to go to university and become a lawyer. Then one day, his village was burned down, and his relatives were killed before his eyes. Scared for their lives, he and his family walked for 10 days before crossing the border to reach safety in Bangladesh.

“How long are we going to be aid-dependent like this?” one young refugee asked me. “We do not enjoy being totally aid dependent. This is our age of working and earning. This latest ration cut is an indication that it is high time we start earning our own money.”

It is critical that donors and decision-makers listen to these young people. They have the right to determine their own future, and to influence how aid dollars are invested in programmes to support them.

A recent assessment conducted by NRC found that Rohingya youth and adolescents are eager to receive vocational training and build technical knowledge, which will help them earn money to support themselves and their families. Some of this training is available, but much more must be provided, and existing initiatives expanded.

For example, some Rohingya youth are being trained on how to repair solar panels while others are trained in tailoring. Alongside this training, the youth now need opportunities to use their newfound skills to earn a living for themselves. And to do that donors, governments and private institutions must put their hands in their pockets and invest further in these initiatives.

Given the opportunity, these young people will be a huge asset to their community and Bangladesh. But the government and donor community must work to provide the tools. Only that way, can young Rohingya have a real chance to take charge of their own futures.