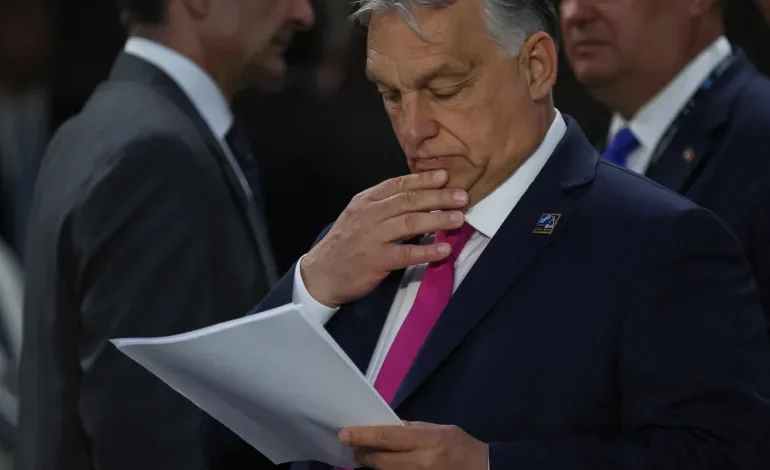

Orban’s ‘peacemaking’ mission: Did Hungary’s leader achieve anything?

When Hungarian premier Viktor Orban broke ranks with the rest of the European Union to visit Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow on July 5, he cast himself as a peacemaker.

“The number of countries that can talk to both warring sides is diminishing,” Orban said, referring to Russia’s war in Ukraine, which he visited on July 2.

“Hungary is slowly becoming the only country in Europe that can speak to everyone,” he added, referring to Russia’s diplomatic and economic isolation from Europe since it launched a full invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

As he assumed the six-month rotating presidency of the European Council of leaders, Orban sought the prestige of a mediator, analysts told Al Jazeera.

“The prospects of peace are so tempting, everyone wants to claim victory and say ‘I brought peace to Europe’,” said Victoria Vdovychenko, programme director for security studies at Ukraine’s Centre for Defence Strategies, a think tank.

“Speaking to Putin and Putin actually listening – everyone wants that as well, because Putin only listens to himself,” Vdovychenko told Al Jazeera.

Putin apparently did listen.

When Orban embarked on his trip, the Kremlin dismissed it as inconsequential.

“We don’t expect anything,” said Putin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, on July 2, when Orban visited Kyiv.

Three days later, when Orban was talking to Putin in Moscow, the tone was different.

“We take it very, very positively. We believe it can be very useful,” Peskov told journalists.

‘Talking to Trump is a new move’

Orban then left for Beijing to speak with Chinese leader Xi Jinping on July 8, an unannounced leg of the trip, before attending the 75th NATO summit in Washington, DC last week.

He went on to meet with Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump in Florida. Trump “is going to solve it”, he was quoted as saying on July 11.

Trump last year boasted he would end the Ukraine war within 24 hours of becoming president, an approach Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy described as “very dangerous”.

“Donald Trump, I invite you to Ukraine, to Kyiv. If you can stop the war during 24 hours, I think it will be enough to come,” Zelenskyy said in a January interview.

“Talking to Trump is a new move and Orban is thinking like a very pragmatic businessman,” said Vdovychenko. “What’s in [his] interest? A fantastic manoeuvre, putting all the autocratic regimes together and bringing them to Trump.”

Did Orban achieve anything? He seemed to think so.

In a leaked letter to European Council President Charles Michel, Orban said Putin was “ready to consider any ceasefire proposal that does not serve the hidden relocation and reorganisation of Ukrainian forces”.

European reactions to Orban’s peace initiative have been unequivocally critical.

“This is about appeasement. It’s not about peace,” European Commission spokesman Eric Mamer said.

Josep Borrell, the EU’s high representative for foreign affairs, said Orban was “not representing the EU in any form”.

Orban’s antics are not new. He is the only EU leader not to allow weapons bound for Ukraine to transit his territory. He and Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer have been the only EU leaders to visit Moscow since the invasion.

Last year, he was the only European leader to attend Beijing’s decennial celebration of its Belt and Road Initiative, a global infrastructure-building programme.

Now, EU member states say they will not attend a peace summit Orban plans to hold on August 28-29, holding their own separate meeting.

A country holding the EU rotating presidency has never been snubbed in this manner before.

European officials have told the Financial Times there have been privately floated proposals to boycott all ministerial meetings during Hungary’s presidency, or to strip it of the presidency completely – an unprecedented move.

Hungary-EU rifts

Orban seems to thrive on confrontation.

Last December, he was the only EU leader to oppose issuing an invitation to Ukraine to open membership talks. The EU’s other 26 leaders overcame his veto partly by offering to unfreeze 10 billion euros ($11bn) in EU subsidies.

In February, Orban opposed pledging 50 billion euros ($55bn) in financial aid to Ukraine for four years. He gave way in a deal whose details have not been revealed.

Then in March, Sweden became NATO’s 32nd member after overcoming another lone Hungarian veto.

The EU governs by consensus, and Hungary’s exceptionalism has made many people angry.

The European Commission’s legal service has said Orban’s peace overtures violate EU treaties that forbid “any measure which could jeopardise the attainment of the Union’s objectives”.

In January, the European Parliament condemned Orban’s December veto and asked the Council of government leaders to investigate Hungary for “serious and persistent breaches of EU values”.

That could have led to a suspension of Hungary’s voting rights and veto, but Europe initiated such proceedings, known as Article 7, against Hungary in 2018 and failed, because the system requires unanimity in the Council. Poland supported Hungary at that time, and it is thought Slovakia or the Netherlands would do so now.

“He wasn’t sufficiently read the riot act in a way that will provide a long-term deterrent. He does not think we’re serious,” said Tallis.

“They’ve chosen Orban four times. They’ve been clear. If there’s a chance of getting kicked out of the EU, getting limited membership of NATO rather than the full thing, then I think it starts to change the equation.”

He added, “A break needs to come.”