‘One of the greatest conservation success stories’: The 1969 mission to save Vermont’s wild turkey

In 1969, a bold plan to restore Vermont’s wild turkeys began with a handful of net-trapped birds from New York. Now the birds gobble around the state in their tens of thousands, even as their populations decline elsewhere in the US. What did Vermont get right?

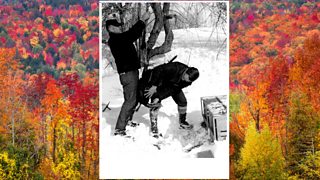

In the early afternoon of 28 February 1969, Bill Drake and John Hall ventured out in the snow. They were near Pawlet, Vermont, walking among nut-bearing oaks and hickory trees, clad in lumberjack shirts, thick woollen socks and heavy boots. The men, both in their early twenties at the time, were also carrying two wild male gobblers from New York. The turkeys may not have known it, but their mission was to help repopulate Vermont.

The biologists’ endeavour, recorded on grainy film showing a colour palette and beanie hats worthy of a Wes Anderson movie, is interesting not only for its fantastic details, including rocket nets and small shelters in the forest, but also because of the legacy of their work. Vermont’s wild turkeys are a successful restoration story, and one that stood the test of time, unlike elsewhere in the United States where wild turkey numbers are now declining.

The fate of turkeys in Vermont are closely tied to its forests. Historically, Vermont was almost entirely covered by woodlands.

“When Samuel D Champlain sailed down the lake which bears his name and he first saw the green forest-clad slopes”, writes Perry H Merril in his History of Forestry in Vermont, “he exclaimed, ‘Voilà les verts monts,’ (Behold the green mountains)”, an expression that was later abbreviated and, according to lore, gave the state its name.

In the mid-1800s, though, land was cleared up to make space for farming, while timber was used for railroads and construction. According to Merril, in a particularly dark note in his History, forests were also cut down because trees were seen as an “impediment to settlement”, and could offer a sheltering place for the Native American Abenaki people who lived in Vermont for over 12,900 years.

The deforestation that followed was deeply harmful for the Native American communities who relied on the forest for food, medicinal herbs and tools. Animals including the wild turkey declined rapidly as the trees were felled, with additional pressure from over-hunting. Eventually, the wild turkey’s population in Vermont was completely wiped out.

A few decades later, though, the picture changed. The Civil War, migration to the West and urbanisation contributed to the decline of farming in the state. Vermont’s forests started to grow back, and today it is one of the most tree-covered states in the country.

Habitat restoration sparked hopes for a turkey comeback. In the 1950s, few bird-loving Vermont citizens started releasing farm-raised turkeys in the verdant mounts. Sadly, the birds were used to farms, not to nature, and they didn’t survive.

Then, in the 1960s, the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department asked New York State for help and were granted permission to catch few New York wild birds and bring them home, hoping that they would like it there, since it was the same native species: the Eastern Wild Turkey, Meleagris gallopavo silvestris.

This bird is now “the most widely distributed and abundant of the five distinct subspecies of wild turkey found in the United States”, according to the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department. These large birds can run at speeds of up to 25 mph and fly at up to 35 mph (40 and 56 km/h, respectively).

Young wild turkey biologist Bill Drake was hired and sent to live trap wild turkeys in south-western New York and bring them back to Vermont. Live trapping a wild turkey is not as easy as one might think.

“He literally had to sit out in the winter in a little blind shelter and then coax these turkeys into an area where he would send a trap net out over them by putting out some corn,” explains Hall, who was then an information assistant at the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department. “He spent the winter of 1968 alone in New York live trapping turkeys.”

John Hall, who at almost 80, is still working at the department, remembers using the net himself at some point, and explains that you could catch a couple of birds at a time – but only if you were very fast.

A turkey comeback in numbers

After the first release of the two male gobblers in February 1969, Drake and Hall released five hens in March that year.

More were to follow: throughout 1969, they released a total of 17 turkeys in West Pawlet (four adult gobblers, one juvenile gobbler, eight adult hens and four juvenile hens). In 1970, they released a total of 14 turkeys near Castleton (two adult gobblers, one juvenile gobbler, two adult hens, nine juvenile hens).

This brought the total number of birds released near Pawlet and Castleton, Vermont, to 31 birds over the two years.

“By the spring of 1973, the population of Vermont’s wild turkeys had grown to an estimated 500 to 600 birds,” Hall says. That year, the department issued the first 579 hunting permits for a 12-day season. But according to Hall, there were few skilled hunters and only 23 succeeded in catching a gobbler.

By 1970, Vermont turkeys were doing so well, that Germany wanted them for their own restoration effort. “Lufthansa airlines sent planes over here specifically to pick up their turkeys,” remembers Hall. “They wanted them badly enough that they were willing to do that.”

Thanks to an ideal habitat and weather, Vermont’s turkey population continued to expand throughout the entire state and is now estimated at 45,000-50,000 birds, who are the descendants of those first New York birds. “The turkeys were our first major restoration effort,” says Hall. “Followed by ospreys, peregrine falcons, bald eagles, American marten, common loons, and muskellunge.”

Mike Chamberlain, the Terrell distinguished professor of wildlife ecology and management at the University of Georgia and director of the Wild Turkey Lab, says efforts such as these in other states led to something of a wild turkey renaissance in the 1960s and 1970s. “It’s one of the greatest conservation success stories in North America,” he says, adding this was largely due to the invention of the rocket net, which made it possible to live trap wild turkeys, and rapidly transport them to areas that needed to be repopulated.

But in some regions, this renaissance was short-lived.

“In the early 2000s, though, not long after restoration ended, population started to decline in many areas, particularly in the south-east United States, and those declines were very gradual,” he says. “It really wasn’t until 2010 and 2011 that we realised that populations had been declining for some time, at least in the south-east. Now, fast forward to 2024, those same declines have befallen many of the states in the Midwest United States. Conversely, in some places, particularly in the north-east United States, turkey populations appear to be doing quite well.”

According to Chamberlain, who has been studying turkeys for 30 years, the decline in the south-eastern states and Midwest is mostly due to loss of habitat, industrial farming and rapid growth of cities in the south-east. “You don’t have extremely large cities in Vermont,” he says. “You’re not seeing widescale forest loss in Vermont. Meanwhile the Midwest looks very different than it did 20 years ago.”

Disease is another factor that may be affecting the turkeys, though Chamberlain says it’s still unclear how much. “We’re also trying to better understand how hunting and harvest affect turkey populations, because hunting pressure is very high in the south-east and in parts of the Midwest, it may be lower in other areas. So that’s some of the things we’re trying to better understand.”

Hunting may sound like a problem for wild turkey populations: why kill turkeys if the goal is to preserve them? But Chamberlain says the picture is nuanced, and there’s a delicate balance to be struck to make hunting sustainable.

“Turkey hunters are an important demographic for this bird, because they spend a tremendous amount of money buying licenses and recreational equipment that generates income for state agencies to be able to manage for the bird,” he says.

Chamberlain himself is a turkey hunter, and has hunted in Vermont. Now he is a scientist, he devotes his work to researching turkeys. He believes that his hunting experience has given him a deeper understanding of the birds’ behaviour and habitat, and he clearly loves them.

“It’s an interesting paradox,” he says.