Oceans littered with 171 trillion plastic pieces

More than 171 trillion pieces of plastic are now estimated to be floating in the world’s oceans, according to scientists.

Plastic kills fish and sea animals and takes hundreds of years to break down into less harmful materials.

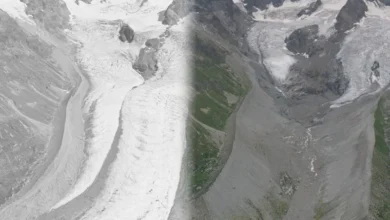

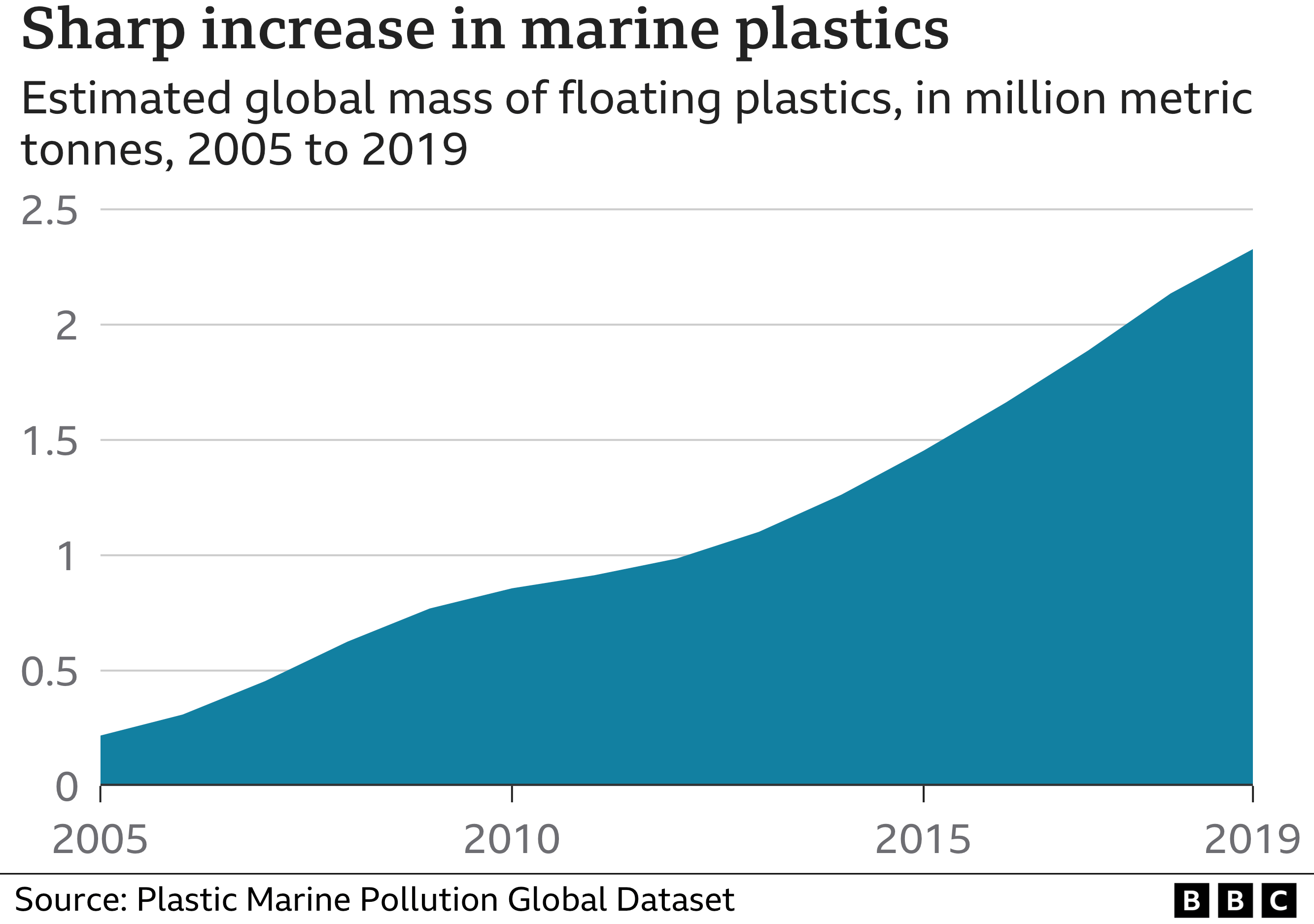

The concentration of plastics in the oceans has increased from 16 trillion pieces in 2005, data suggests.

It could nearly triple by 2040 if no action is taken, scientists warn.

Last week, nations signed the historic UN High Seas treaty aiming to protect 30% of the oceans.

To produce this new estimate, a group of scientists analysed records starting in 1979 and added recent data collected on expeditions that trawl the seas with nets to collect plastics.

The plastic counted in nets is then added to a mathematical model to produce a global estimate.

The 171 trillion pieces are made up of both recently discarded plastics and older pieces that have broken down, lead author Dr Marcus Eriksen from the 5 Gyres Institute told BBC News.

Single-use plastics like bottles, packaging, fishing equipment or other items break down over time into smaller pieces due to sunlight or mechanical degradation.

Wildlife like whales, seabirds, turtles and fish mistake plastic for their prey and can die of starvation as plastic fills their stomachs.

They also make their way into our drinking water, and microplastics have been found in human lungs, veins and the placenta.

Scientists say we do not yet know enough about whether microplastics negatively affect human health.

The concentration of plastics in the oceans has significantly increased from around 16 trillion pieces in 2005 to 171 trillion in 2019.

Before 2005 the concentrations fluctuated. Dr Eriksen says scientists are not sure why this is, but it could be explained by stronger legislation being replaced by voluntary agreements, the breakdown of plastics, or the fact that less data was collected.

Prof Richard Thompson at Plymouth university, who was not involved in the study, said the estimate adds to what scientists know about marine pollution.

“We are all agreed there is too much plastic in the ocean. We urgently need to move to solutions-focused research,” he said.

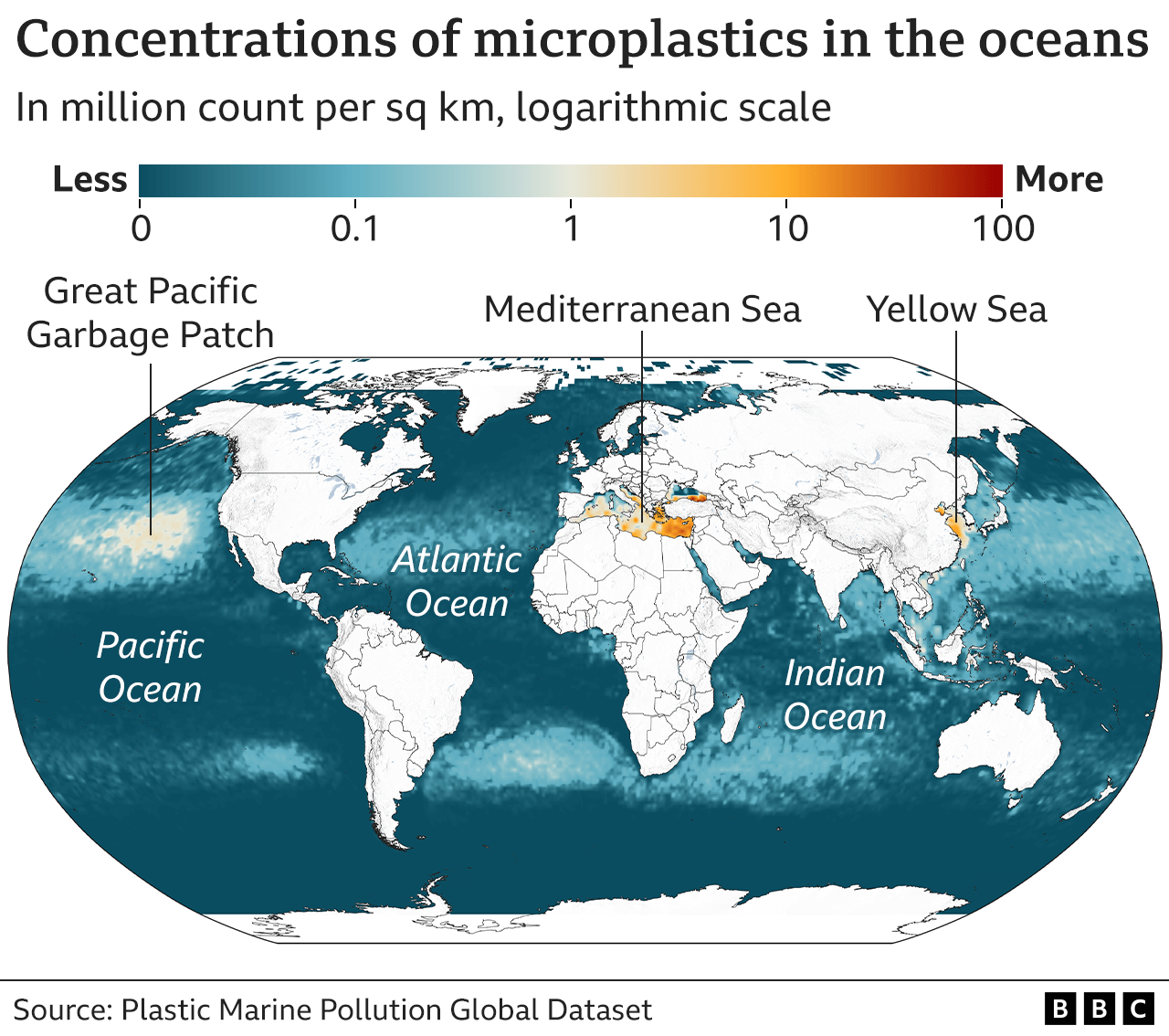

The highest concentration of ocean plastic is currently in the Mediterranean Sea, with some large floating masses found elsewhere including the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

The authors also suggest that the changing levels of pollution before 2000 may be due to the effectiveness of treaties or policies that govern pollution.

In the 1980s several legally-binding international agreements mandated countries to stop discarding fishing and naval plastics in the oceans, as well as to clean up certain amounts.

These were later followed by voluntary agreements which the authors say may have been less effective, and could explain the rise in plastics from around 2000 onwards.

The authors argue that solutions must focus on reducing the amount of plastic produced and used, rather than cleaning up oceans and recycling plastics because this is less likely to stop the flow of pollution.